Info

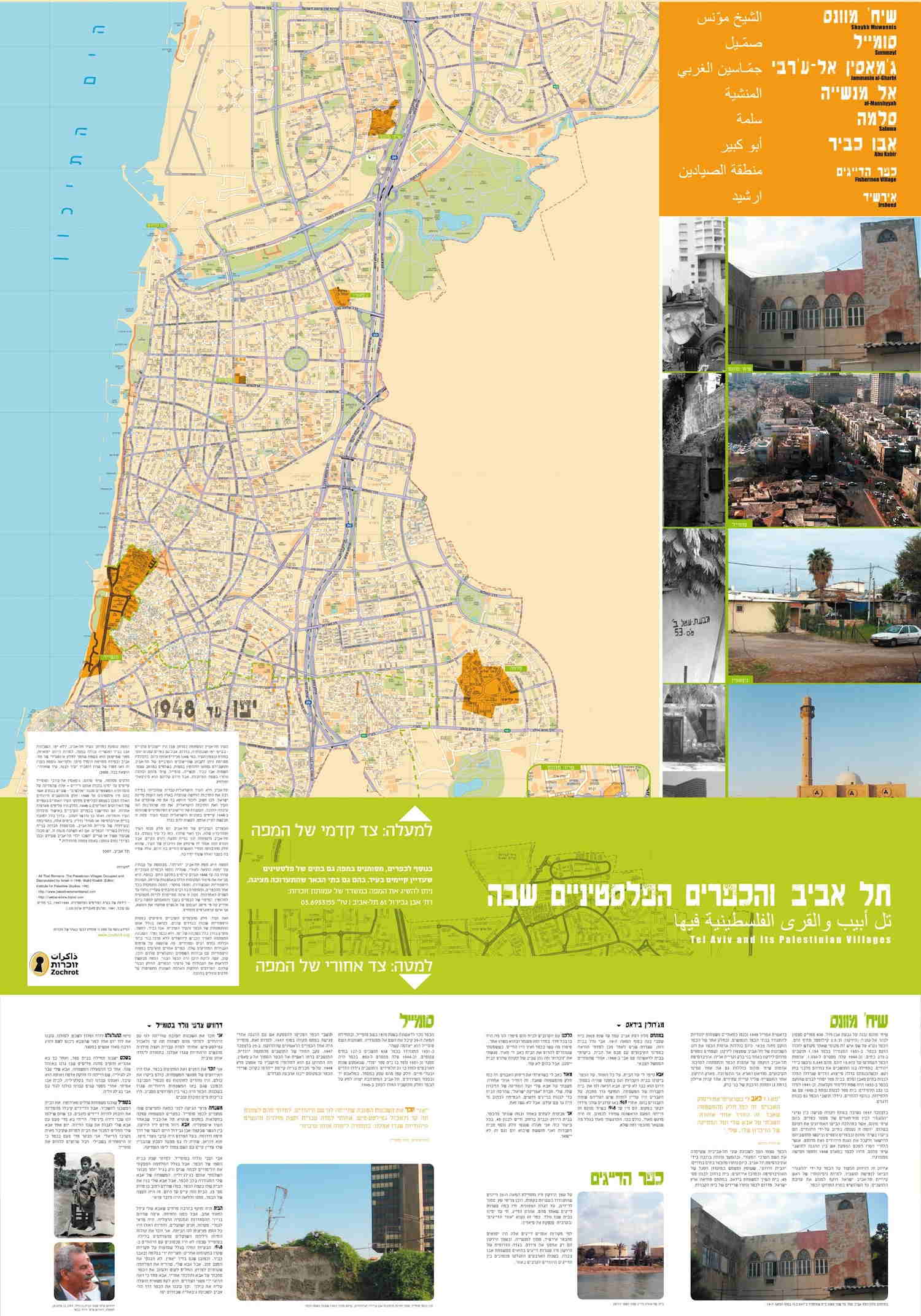

District: Jaffa

Population 1948: 13000

Occupation date: 24/04/1948

Occupying unit: Irgun (Etzel)

Jewish settlements on village/town land after 1948: Tel Aviv expansion

Background:

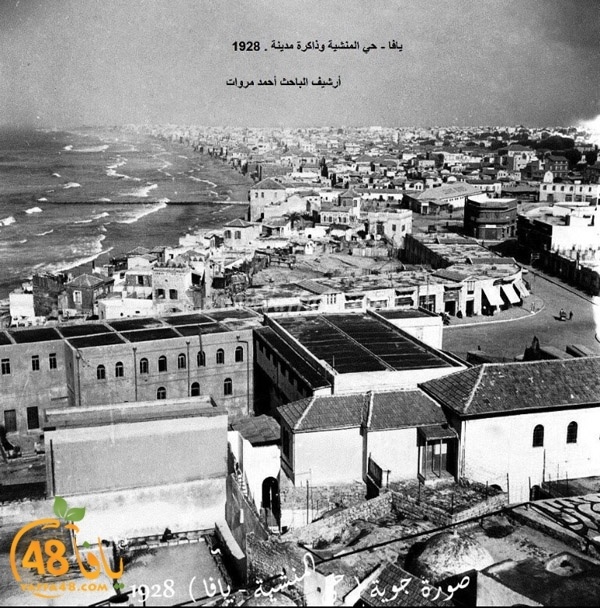

The year 1879 was a turning point in the history of Yafa (Jaffa). Demolition began of the crumbling city wall, which had been neglected for decades. The immediate result was the creation and rapid spread of the new Ajami and Jebalya neighborhoods south of the old city, Manshiyya to the northeast and al-Nuzha to the east.

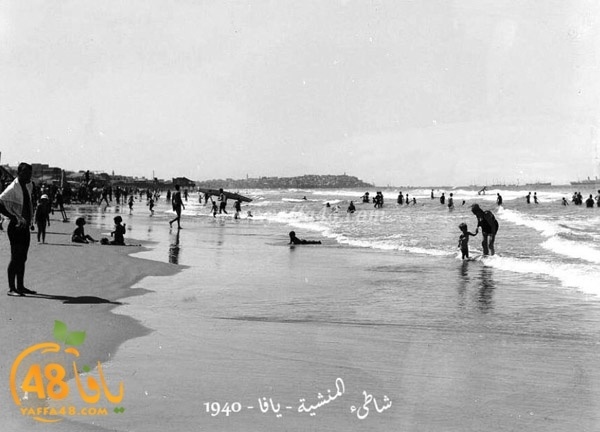

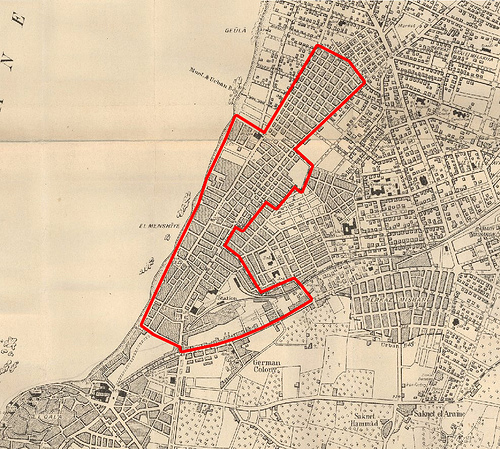

Manshiyya was established at the end of the 1870’s, on the seashore, and became one of Yafa’s largest Arab neighborhoods. The first Jewish neighborhoods surrounding Manshiyya, Neve Tzedek and Neve Shalom, were built soon afterwards, in 1885 and 1890, respectively. The establishment of these two neighborhoods encouraged Jews to purchase land for the erection of additional neighborhoods in the vicinity, between 1896-1906, including Yefe Nof, Ahva, Mahane Yehuda, Mahane Yosef, Ohel Moshe and Kerem HaTeimanim. The last of them, Tel Aviv, was founded a few years later, in 1909. These neighborhoods did not spread out from Neve Tzedek and Neve Shalom, as is commonly believed, but grew around Arab Manshiyya and to the west, away from the sea. The first Jew who built in Manshiyya, near the sea, even before the Jewish neighborhoods were established, was Haim Shemerling. His friend, Haham Moshe, a member of the Jewish community council, built his own house not far away. He also erected a synagogue and a ritual bath (mikveh) to meet the religious needs of the two families. Jews continued to live in that area even after the establishment of the Jewish neighborhoods surrounding Manshiyya; some built homes, and others rented homes from the Palestinian residents. The neighborhood was built of a combination of one- and two-story buildings, stretching along the shore. According to a 1944 local police report, the population of Manshiyya numbered some 12,000 Palestinians and about 1,000 Jews, on an area of some 2,400 dunums. Although there were many citrus groves in the area, most of Manshiyya’s residents were engaged in commerce. According to the 1944 police report, Manshiyya had 12 bakeries, 20 coffee houses, 14 carpentry shops, 3 bicycle repair shops, 5 doctors, 7 factories, 7 jewelers, goldsmiths and silversmiths, 6 hotels, 10 laundries, 3 pharmacies, 3 printers, 6 restaurants, an electrical power plant and other commercial establishments. Most of them were located on HaTahana Street, in the Jewish market, al-‘Alam Street and Hassan Beq Street.

Manshiyya had three Arab mukhtars, Haj Hamis al-Omari, who lived on al-‘Alam Street, and Haj Hassan, who lived on Hassan Beq Street and Abu Ahmad al-Sharkawi. The Jewish mukhtar was Moshe Levy, with authority over the Jewish residents; they called him Moshe Alful.

Al-Mahta (HaTahana) Street, and the Al-Rashid neighborhood

Al-Mahta Street started at the intersection of Bustrus and Jamal Pasha Streets, north of the old city of Yafa. This was where the Al-Rashid neighborhood began. It was built at the same time as Manshiyya and was located between it and Yafa.

Manshiyya had been built outside Yafa’s walls by Egyptian soldiers from the village of Al-Rashid, on the banks of the Nile, who had remained in Yafa following the withdrawal of their leader, Ibrahim Pasha, who had ruled Yafa from 1831 to 1834. These soldiers had also lived in other Yafa neighborhoods, such as Saknat Darwish, Abu Kabir and Tel Alrish. The only structure remaining from that neighborhood underwent “restoration and preservation” at the beginning of the 1980’s, and when the work was finished in 1983 the building was turned into the Etzel Museum, named for Amichai Gidi (the Etzel’s operations officer), commemorating those who captured Manshiyya.

Manshiyya’s HaTahana Street was narrow and crowded, filled with shops, homes, merchants, pedestrians and United Bus Company vehicles, and carriages pulled by a one or two horses. The street was named HaTahana (Station Street) because of the Yafa – al-Quds (Jerusalem) railway station which was located there, built in 1892 by a French company. Over the years, a number of buildings were constructed at the station, including the compound of the Wieland family, who were Templars. During the 1948 war, the station served as the Etzel’s rear headquarters and as a recruiting base. It is currently undergoing a major renovation as a recreational and cultural area.

Al-Naj’ada (1945-1947), an organization that developed from the Moslem Youth Association, intended to form the core of a Palestinian military group, was located in a building next to the station. But the events of 1947-48 began before the group had been able to coalesce, and led to its dissolution. The Islamic Scout Movement also had a building in the area.

HaTahana Street stretches north to the area known as the “Jews’ market.” Until 1947, the market contained a number of shops owned by Jewish merchants, as well as many owned by Arabs. On the eve of 1947, however, the Jewish merchants left Manshiyya for the adjoining Jewish neighborhood of Shabazi. According to Saleh Masri, who had been uprooted from Manshiyya and today lives in Yafa, this is how the market got its name: “I heard two different stories. The first was that they called it the Jews’ market because of the Jewish merchants, and the second was because of the Jewish prostitutes who worked next to the market, between Manshiyya and Neve Tzedek – that’s why it was called the Jews’ market.”

At the entrance to the Manshiyya neighborhood, on the west side of HaTahana Street, on al-‘Ghazali Street, was one of the largest and most famous coffee houses in the area, Café Al’ansharah. It was a meeting place for political leaders, public officials and important businessmen. Across the street was a small bakery, owned by German immigrants who worked in the area. On the other side of the street was another café, less well-known, Café Mid’ha, named for Hassin Mid’ha, the owner. It was considered an inexpensive, popular coffee house, most of whose patrons were older residents of the neighborhood.

As it went north, HaTahana Street became Al’Alam Street. Café Al-Lamdani was located here, one of the most famous popularly-priced coffee houses in the city. North of Al’Alam Street was the Carmel Market, which still exists today, where Palestinian and Jewish merchants had their shops, and from which Tel Aviv developed.

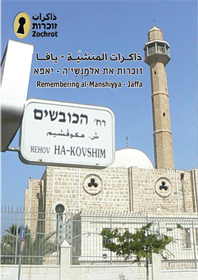

The Hassan Beq mosque neighborhood

The Hassan Beq mosque, also known as the New Mosque, was built at the northern end of Manshiyya in 1914, on the eve of the first World War, by Hassan Beq al-Jabi, the Turkish governor. During his rule, Hassan Beq encouraged the development of Yafa and its neighborhoods. The mosque, along with the area of the railroad station, are the only buildings remaining from Manshiyya, and dozens of worshippers, most of them from Yafa, continue to pray there.

Hiri Abu Aljaban describes, in “Yafa Tales,” how the mosque avoided demolition by the authorities. “One of my friends, Wahid al-Jabari, the son of Sheikh Muhammad Ali Al-Jabari, the mayor of al-Halil (Hebron) and a former Jordanian minister, told me that his father asked his friend, Golda Meir, the Israeli Prime Minister between 1969 and 1973, not to demolish the mosque; she agreed, and allowed it to remain.”

Saleh Masri related another story about the survival of the mosque until today:

"The authorities refused to allow us to pray in the mosque after 1948 and it remained deserted for many years after the destruction of it's tower, and they wanted to make a museum out of it. During the sixties some people from Jaffa gathered and we decided to form a special committee to protect the holy sites in the city. Until then, the mosque was deserted and dirty from the sheep and goats that were kept in it. At the beginning of the seventies we managed to get permission to reopen the mosque, but with heavy security, since some people from the Jewish neighborhoods refused to have it reopened and threatened to hurt us. We gathered some money together and hired a construction worker from Nazareth to fix the tower."

The Al-Marwaniya School for boys was next to the mosque. Its library contained 1,608 volumes. A small hill near the mosque was known as “Bidas Hill,” because the wealthy Bidas family had built a large palace on it. As time passed, that hill became an important neighborhood symbol.

Al-Manshiyya Street was south of the mosque. There were two schools on the west side of the street, al-Amoya, in which boys and girls studied together, and al-Abassiyya. The Moslem Youth Association, founded in 1924, was next to the schools, and played an important role in raising the national consciousness of the Arab youth and in community activities such as establishing schools and clinics.

1936-1948

Tel Aviv expanded rapidly in the 1930’s and 1940’s, and found itself surrounded by Arab localities – Sheikh Muwanis, Jamasin and Sumeil to the north, Salameh, Yafa and Manshiyya to the south. Maps from the period show Manshiyya as a long strip separating Tel Aviv from the sea.

The Arab Revolt began in 1936. Palestinians protested against the policies of the British Mandatory government and against Zionism and the immigration of thousands of Jews. Prior to the revolt, the Manshiyya neighborhood might have been a bridge between the two towns, a hyphen connecting Tel Aviv and Yafa. But from the start of the revolt until 1948, the Jews saw Manshiyya as the most serious threat to Tel Aviv and the surrounding Jewish neighborhoods. That might be the reason that Nahum Gutman, the Tel Aviv artist, whose paintings portray “Little Tel Aviv” and the other Jewish neighborhoods of the 1930’s, failed to see Manshiyya.

Only a few days before Operation Hametz, whose aim was to surround Yafa and cut it off from the surrounding Arab villages, the Etzel began a direct attack on the Manshiyya neighborhood. In order to conduct the operation, the organization brought in units from different areas of the country, and according to Etzel sources they numbered some 600 fighters with a large amount of ammunition and grenades, some of which had been stolen a short time earlier from a British military train near Pardess Hannah.

The Etzel attack was aimed at cutting Manshiyya off from the rest of Yafa, overcoming and capturing it. Administrative mishaps delayed the start of the operation. The attack, which was to have begun at night, only commenced at dawn on April 25, with the attackers still lacking sufficient supporting weapons. They failed to gain their objective that day, or during that night. British military reinforcements were sent to the city, and the authorities issued a stern warning to cease the attack. Nevertheless, the Etzel renewed its attack on the morning of April 27, and reached the seashore after having sustained fairly heavy casualties. The residents of Manshiyya and the other villages tried to resist. They gathered, primarily around the Hassan Beq mosque, and tried to fight, despite their small number and lack of weapons. As the fighting continued, the number of killed and wounded increased, until Manshiyya finally fell on 28 April 1948, and was cut off from Yafa. The Haganah then started Operation Hametz, whose aim was to capture Yafa and the villages to the south and east.

The British demanded that the Etzel surrender to them the Manshiyya police station, and open Hassan Beq Street between Yafa and Tel Aviv, in the southern part of Manshiyya, to permit the passage of British military vehicles and personnel. The following day the Etzel blew up the Manshiyya police station and planted the Jewish flag on its ruins. The southern part of the neighborhood became an area of demolished buildings. Structures on both sides of Hassan Beq Street were dynamited, making it impossible for British vehicles to enter Manshiyya from Yafa. Using loudspeakers, the Jewish forces went through the streets of Manshiyya calling on Palestinian fighters to turn in their weapons and surrender. Some were taken prisoner.

After Manshiyya fell, the Etzel formally transferred the entire area of the conquered neighborhood to the Haganah, with the aim of stabilizing the boundary of the captured area on Manshiyya’s southern border. On the same day it issued the following announcement: “At dawn on Saturday, 22 Nissan 5708, the southern portion of liberated Manshiyya became a ruin. The Manshiyya police station no longer exists.”

Some of Manshiyya’s inhabitants were expelled to Jordan, and others were sent by sea to Gaza and Egypt. A few were transferred to Yafa and later lived in the ‘Ajami ghetto, alonside refugees from Yafa and the nearby villages. On 28 April, HaMashkif published the following description of Manshiyya:

“Piles of ruins wherever you look, gaping holes in walls, ruined belongings, streams of water flowing from open faucets in destroyed buildings and…deathly silence. ‘That’s what Manshiyya is like today. The silence is broken from time to time by a shot…fired by our reconnaissance forces’ – is the explanation provided to us by Gid’on, the commander who led the heavy fighting with the Arabs and poured heavy fire on the attackers from their ‘Spandaus’ and ‘Brens.” In most cases, the attacking Etzel forces advanced using engineering tactics by breaking through the walls of buildings, into the heart of Manshiyya…at other times, when the attackers captured a position, they dragged the sandbags they found there as they advanced, using them as shields from enemy fire. When the attackers reached Al’Alam Street, in the heart of Manshiyya, they confront two frightening positions on either side of the road, and the advancing waves were stopped. Then the lads blew up the masses of buildings on each side of the street, the firing positions collapsed and piles of ruins covered the road.”

After being captured by the Etzel, the neighborhood was demolished in stages. In fact, the Tel Aviv municipality had planned its demolition when the fighting ended, a plan that failed when, as early as June, 1948, Jewish immigrants moved into the abandoned homes. Manshiyya rapidly became a poor Jewish neighborhood to the south of Tel Aviv.

From neighborhood to lawn

Manshiyya gradually turned into a site for Israeli architectural experiments and became publicly owned. In the 1950’s, development started on plans for the site’s future. One of the most prominent plans was “The City,” the creation of an urban center for the new, modern city. “It is as if the Manshiyya site,” wrote the planners, “has been designated from time immemorial to serve as the new city center.” But there were still some people living in the neglected neighborhood who hadn’t heard about this plan, and weren’t ready to vacant their small homes facing the sea. The municipality’s decision to freeze construction in the neighborhood was the beginning of a process which ended with its complete erasure, in the course of which the municipality stopped maintaining the buildings and allowed it to become a junkyard.

The authorities’ intentional indifference to neighborhood conditions led to the departure of most residents. The only ones remaining were those who were too poor or too ill to leave. The neglect confirmed the public impression of the area as a wretched place, inhabited by people who were a burden on society.

In 1963, it was decided to allow construction in Manshiyya, to transform it into a modern commercial center. “Ahuzat HaHof,” a joint government-municipal company, was established, and an international competition was announced for the design of the site. The plan was to include public buildings, a commercial and shopping center, office towers and thousands of housing units, parking lots, hotels, leisure and recreational facilities, maximizing public access to the seashore. Manshiyya was demolished completely, except for the Hassan Beq mosque. A park was created opposite the mosque as a memorial to the forces that captured Yafa, adjoined by parking lots and the final stop of some city bus lines. The climax was Charles Clore Park, named for a Jewish British philanthropist, designed by E. Hillel, the landscape architect and poet, established on most of Manshiyya. The rolling surface of the park formed “dunes” concealing the rubble remaining from the demolition of the neighborhood, which had been pushed to the seaside. In the Zionist tradition of making the wilderness bloom, the dunes were covered with grass and colored green.

The Manshiyya project, like other places in Yafa, is an example of how the process of destruction, which started with an attack on the neighborhood, continues even now, in the guise of “planning” or “development.” In fact, Manshiyya today looks exactly like Nahum Gutman’s images.

Videos

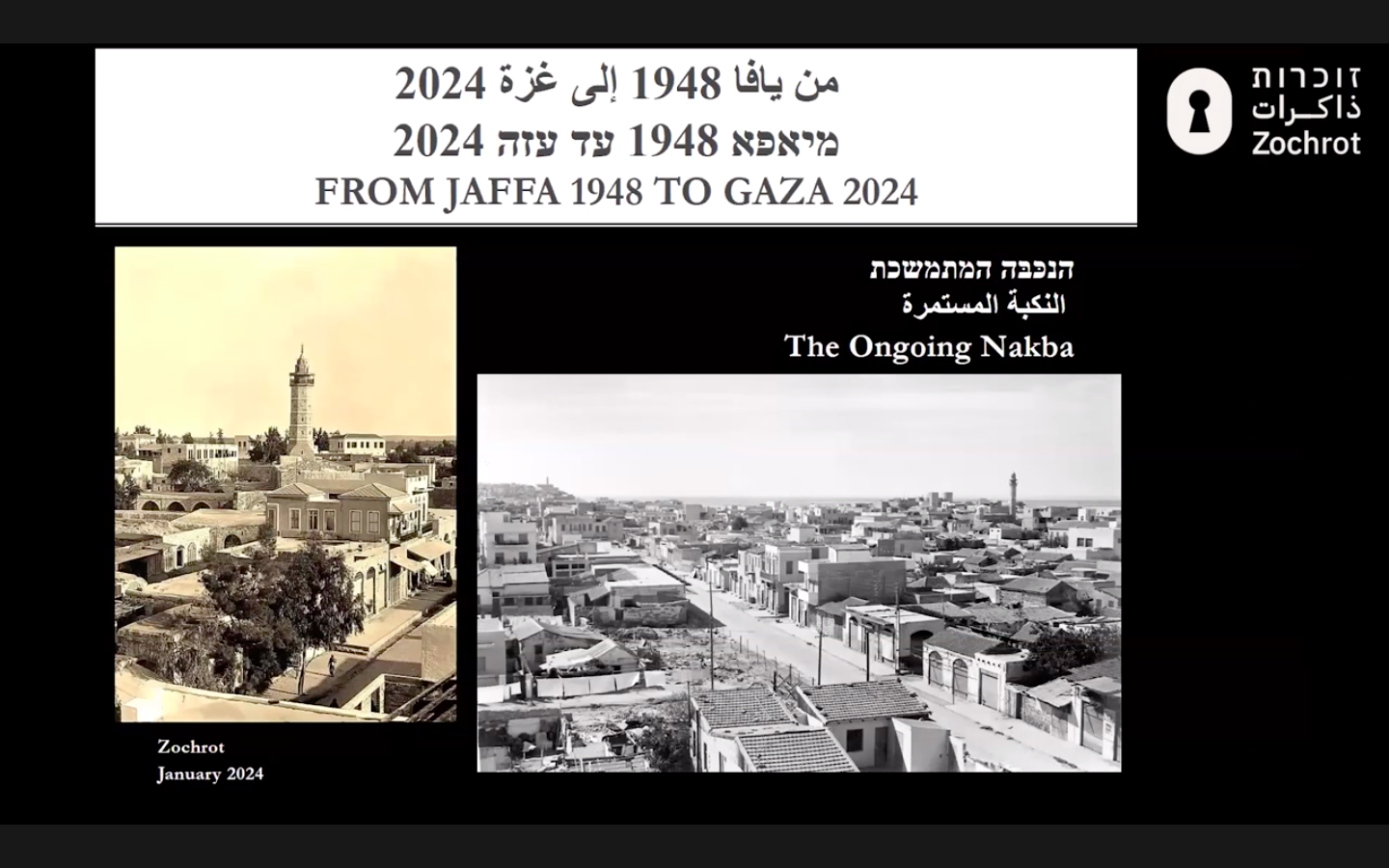

A Virtual lecture and tour, via Zoom, about the history of Jaffa, the largest and most important city in pre-1948 Palestine Jaffa – its occupation and ethnic cleansing.

This Zochrot film tells the story of Saleh Masri and Iftikhar Turk, two internally displaced Palestinians from the al-Manshiyya neighborhood of Yaffa city.

Zochrot would like to thank Trocaire for their support of the tour to Manshiyya and film.