Tuesday afternoon, October 5, 2004, the "Zochrot" bus. Eitan passes out bus tickets for line 194 ("Happy Return"), and again we are on our way. The destination this time is the remains of al-Lajjun, a village that existed until 1948 at the site of what is now called Kibbutz Meggido. We are 40 people, Jews, Arabs, and also many guests from abroad, volunteers in Palestine-Israel.

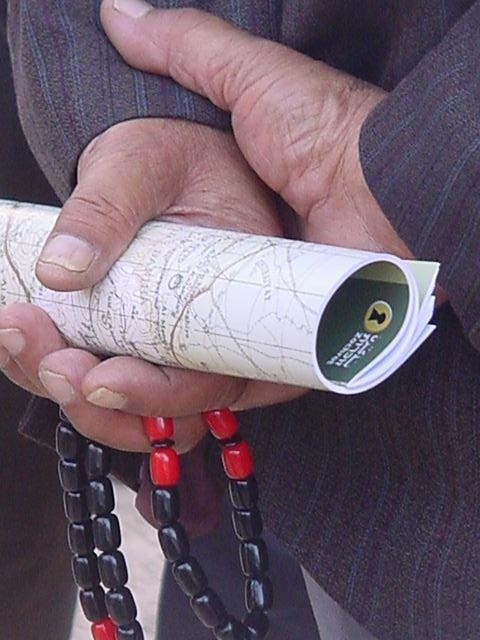

At Meggido Junction, next to the annual Peace Tent of "Bat Shalom," another hundred men and women join us. The buses continue to the area of the kibbutz, around fields, groves, and empty land. Adnan turns on the microphone, and welcomes the passengers, "Welcome to Lajjun, our dear, beloved village," and we look out through the wide windows, like tourists.

The first stop is the Mahamid neighborhood. We disembark into the pine grove at the top of the hill, and meet the refugees of the village. Adnan, who was in born in Lajjun, tell us that it was divided into a number of neighborhood, and this is one of them. After the war, when the houses were destroyed, trees were quickly planted there, to cover up the injustice. But the old, stubborn stones still peek out from the earth here and there.

Nearby is the old village cemetery. The relatively small plot is fenced closed, and a sign in Hebrew and Arabic designates the place. It turns out that in the past the Kibbutz would throw its garbage precisely here. After the refugees of the village cried out, the deceased minister Zevulun Hammer intervened and the disgrace came to an end. On the other side of the cemetery fence hangs another sign that reads: "Holy Site, No Entry."

The path winds at the top of the hill, beside the remains of orchards, and we can already see the old mosque. The structure remains standing, and in the past the kibbutz "permitted" the displaced residents of the village to come visit from time to time. But this generosity was overcome by the fear of "upsetting the status quo," and this time we are not even allowed to come near it. A network of wire fences prevents entry, and a police Jeep is up there, watching us. In the meantime we hear that the holy place served as the carpentry workshop of the kibbutz, and even a dog lived there.

In the end all of us gather beside the old water well called "Ayn al-Khajja," which is called thus, Adnan says, in honor of the beloved women of the village. They say it overflowed with good mineral water. The residents of Wadi Ara would come to fill jerry cans of water, particularly at Ramadan, until the kibbutz decided to put a stop to it, and diverted the water flow. Today in the waters of the small pool that remains, we see pieces of old cardboard, a plastic bottle, and all kinds of floating insects. A young girls tires to remove the refuse from the water. And from the stream of water remains only a drizzle.

We sit in a semi-circle on plastic chairs that were positioned on a small patch of grass, surrounded by low-lying hills. The sun is about to set. Someone plays the recorder, and then someone takes out an oud, and everyone claps hands to the rhythm, and those who know the words join in song. Surounded by these sounds, it is easier to imagine how the place was a few decades ago. The fields, the fruit orchards, the trickling of the well, the voices of people. A warm feeling of family envelopes us here, all of us. And the thought, that everything could be different.

Lajun Tour 2004 (13)

Lajun Tour 2004 (10)

Lajun Tour 2004 (12)

Lajjun_Chris_Seidel_2004 (10)