The village of Sabalan, or al-Mazar (a pilgrimage site), named after the tomb of the holy man, Nebi Sabalan, is located northwest of Safed, at a height of 814 meters above sea level.

Diya Hasin Muhammad Omar-Fa`ur (1916), whose father had been the village mukhtar, had been involved in all aspects of village life, and the tales she told us came from her store of memories:

I was born in Sabalan and was married there twice. My first marriage was to my cousin, and together we moved into my uncle’s house, which still stands today. When my husband took ill and died, my family married me to my brother-in-law, and we remained until we fled.

We were happy in Sabalan. The village had no spring, and people would go down to Wadi Alhabis to get water and to bathe. The Wadi was far away and the women would go down with donkeys, load them with four containers of water and carry another on their head so they’d have enough for watering the cattle, drinking and bathing.

There were two wells in Sabalan, which still exist today: a well for visitors, below the cemetery in the western part of the village, and a well from which we drew water for the sheep, next to the holy tomb, below my family’s house. My girlfriends and I would cut wood, load it on our head, and whoever carried best was the winner. But the poor men – they had to cut wood while they rode on the animals (laughs).

Yusuf Muhammad Fa`ur (1928), who now lives in Hurfeish, ( a village in the Upper Galilee) emphasizes:

All the women worked in agriculture, sowed tobacco, picked olives, grapes and figs, and plowed the fields. Our village was famous for its tobacco, and companies would come to the village to buy tobacco from the fellahin. Although the village had no shops, flour mills or olive presses, it wasn’t poor, and people maintained themselves. We’d work the land and make a living from it, and most people had land in the village.

The rebels leave, and the English come

Diya continues retrieving her memories, and tells us about the Englishmen:

what can I tell you about them – they slaughtered us. They’d come and break up the barrels of olive oil, scatter the flour and lentils all around, spread them on the porches and stamp on them with their leather boots. They’d gather the young men, tie them up, put them all together in one place. They’d gather the women, tie them up and put them somewhere else.

Once the English came to the village and someone from Hurfeish was hiding from them. He was wearing light sandals, masquerading as a woman, and sat with the women. One of them, who wanted to urinate, got up, removed her clothing and squatted down in front of the women, while he was hiding among them (laughs). The English tortured the men very badly, and sometimes pulled down their underwear and made them sit on cactuses.

Yusuf Muhammad Fa`ur (1928) tells us about the murder of his brother, Reda Fa`ur:

The English came to the village whenever they chose, surrounded it, searching for rebels and weapons. They would humiliate anyone they caught, in front of the other men. There were four sons and four daughters in our family in Sabalan – the English army shot my brother Reda at the beginning of 1939.

My brother was married and had children, and would visit his wife’s family in Dayr Al-Qasi (Alkosh Settlement today). His wife’s brother had a rusty pistol that didn’t work, and gave it to him so he could bring it to someone in Buqei`a to be repaired. On the same day he came back to Sabalan the English surrounded the village and caught him with the gun. They took him to the village center, tied him up, gathered all the families in the village, and shot him before their eyes. I was a little boy then, standing among the people, and I saw my brother die. When he was killed he left a daughter and a wife in her final month of pregnancy.

The English caused us a lot of damage. They would arrest the men during the cold winter weather, bring freezing water and dunk their heads into it.

The expulsion

The village of Sabalan was captured on 30 October 1948, during Operation Hiram. The Israeli soldiers entered the village while a white flag flew from the dome of the holy tomb.

When we asked Grandmother Diya what she remembers about they day they left, she quickly replied, as if her memory had suddenly come alive:

I remember everything. People began saying, “The Jews captured Haifa and reached Sa`sa` (Kebbutz Sasa today), the Jews captured Haifa and reached Sa`sa`.” The refugees fled to our village and spread out between the grape vines and the olive trees. The women grabbed the children and fled to the woods. The men had been defeated in the fighting, and the old men remained in the village. When the Jews came to my father, who was the Mukhtar, he raised a white flag among the domes of the holy tomb and when the Jews saw it they clapped him on the shoulder, saying: “You’re a good Mukhtar, and you’ll live here as well as you did under the English, and even better. But where are the village’s families?”, he asked. “The families went into the woods because they’re afraid of the planes and of the army.”

They told him to go out and announce that the Jews have surrounded the village, and that anyone returning before 6 AM would die. My father went out and called to the families not to return before 6 AM.

When 6 AM came, we got up, returned to the village, and people were happy. Four or five days later the army returned and surrounded the village. This time there were many Arabs with them – that is, not all of them were Jews. They asked the women to slaughter the chickens and cook them for the soldiers. I remember us slaughtering about one hundred chickens, and a little later they came to me and told me my husband had been tied up, and they want to shoot him. I ran and saw they’d tied him up. He told me: “Run and tell my mother to go to Hani Nassif from Hurfeish, who’ll talk to the army so they won’t kill me.” My husband’s mother went to Hurfeish. Soldiers met her on the way and said, “Woman, you’d better go back so we don’t shoot you.” She replied: “I don’t want to go back, I’m going to get butter so I can cook the chickens for you.” So they let her alone and she went to Nassif who came, released my husband and they didn’t shoot him.”

Immediately afterward they came and lined up the men and women separately, and said that anyone found in the village one hour from now will be killed. I ran in one direction and my husband ran in another direction. My four children and I fled toward Wadi Al-habis, and from there to Hurfeish, to Abu Nimr’s family who received us, welcomed us and took us in. My family emigrated to Lebanon, and I never saw them again.

My husband hid in the woods, and the next day came to Hurfeish. When he arrived he was worried about me and the children – he put us on a camel, with a mattress and a kilo of white flour, hired someone to take us to Lebanon, and said that if he sees that the situation improves he’ll come take me from Lebanon, and if he sees that the situation is difficult he’ll join us there.

When the government of Israel began enumerating the population and carrying out censuses, my husband went to bring us back from Lebanon. We returned via the Sa`sa` valley and passed through The sheepfold. I remember placing a can of sardines, the kind we ate in Lebanon, in my son Muhammad’s pocket, and Ansaf, my daughter, was still nursing. When we neared The sheepfold my husband told me to walk in front of him, and he’ll follow, because the army might be in The sheepfold. It was the middle of the night, and very cold. When we came to the outskirts of The sheepfold I heard the sound of a gun rattling. I was afraid and went back, and suddenly found myself facing three soldiers. I began screaming and yelling, “Women, women, women…” and the children began crying and shouting. The soldiers came, put their hands over the children’s mouths and listened to hear whether anyone was with me. One of them asked me, “Who’s with you?” I said, “No one’s with me.” Then he asked, “How did you get here by yourself?” I answered: “My husband is in Hurfeish and my family is in Lebanon, and I want to be with my husband.”

Then he said to me: “No, whoever is in Hurfeish is in Hurfeish, and whoever is in Rmesh (a village in Lebanon, on the border) is in Rmesh, and if you’d been a man you’d have been dead long ago. Go back to Rmesh.” They pulled the children along with me, brought us to the road, told me to walk to Rmesh and began shooting around our feet. We went down – there was a spring nearby and I sat on a rock, placed my daughter at my nipple and fed her. My son rested under a jadu’a tree, took a sardine can and dug into the tree, while the snow fell on us without stopping. The boys and girls came to me saying, “Mother, are we going to die?” “Thank God,” I answered.

Suddenly someone from al-Maghar ( a village in the Upper Galilee) appeared and asked what I was doing here. I told him my story, and when I asked him what he’s doing here, he said that about a dozen people from al-Maghar were on their way back to Israel, and when they heard gunshots he told the others he didn’t want to continue, and decided to return to Rmesh.

He gathered the children together, put them on the horse, and led me, in the lead because he was afraid of robbers, and that’s how the children and I returned to Rmesh. We were very tired and cold and the children’s feet were swollen from the cold and the walking. We remained in Rmesh three or four days, and then my uncle’s family sent a Druze man from Hurfeish to bring me back. When we returned with him we didn’t come from the direction of Sa`sa`, but from Dayr Al-Qasi. On the way we ran into about 20 smugglers who carried goods from Lebanon on their back, and had guns. We were very fearful and I didn’t notice that the Druze fled into the woods and left me and the children by ourselves. The smugglers saw and stopped me, but then allowed me to continue on foot to Hurfeish.

What remains of Sabalan…

Only the cemetery is left, the well and four buildings, including the house of the Mukhtar, Hussen Omar, Diya’s father, and the house in which she was married. Today those buildings are used by visitors to the holy tomb of Nabi Sabalan. Most of the families from the village emigrated to Lebanon, and only four families moved to neighboring villages. About 200 emigrants from Sabalan remain today in occupied Palestine.

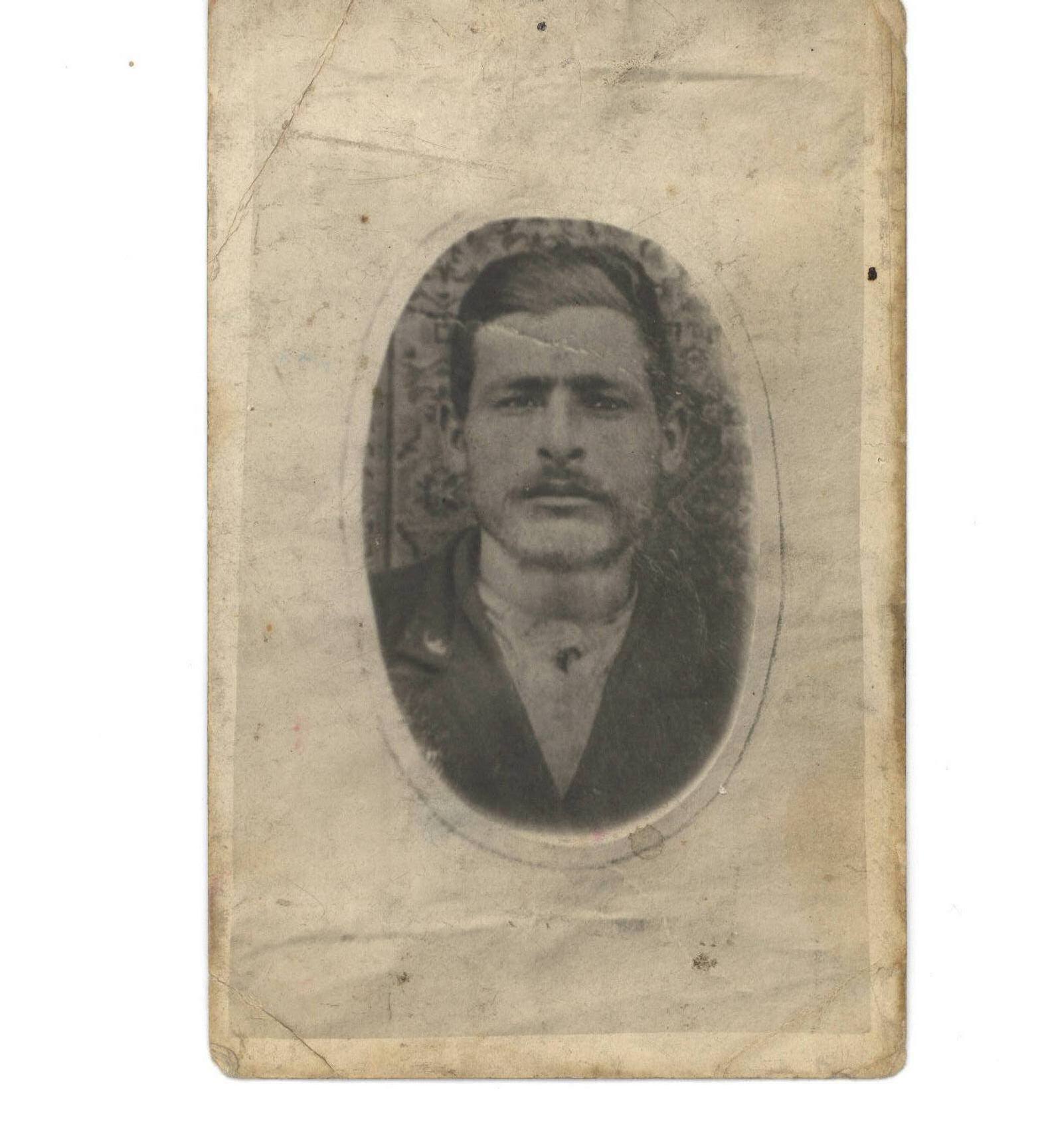

احمد نايف فاعور زوج الحاجة ضيا / אחמד נאיף פאעור, בעלה של אלחאג'ה דיא

محمد احمد فاعور / מוחמד אחמד פאעור

ما تبقى من بيوت النبي سبلان / מה שנשאר מבתי הכפר סבלאן

مقبرة قرية سبلان / בית הקברות של כפר סבלאן

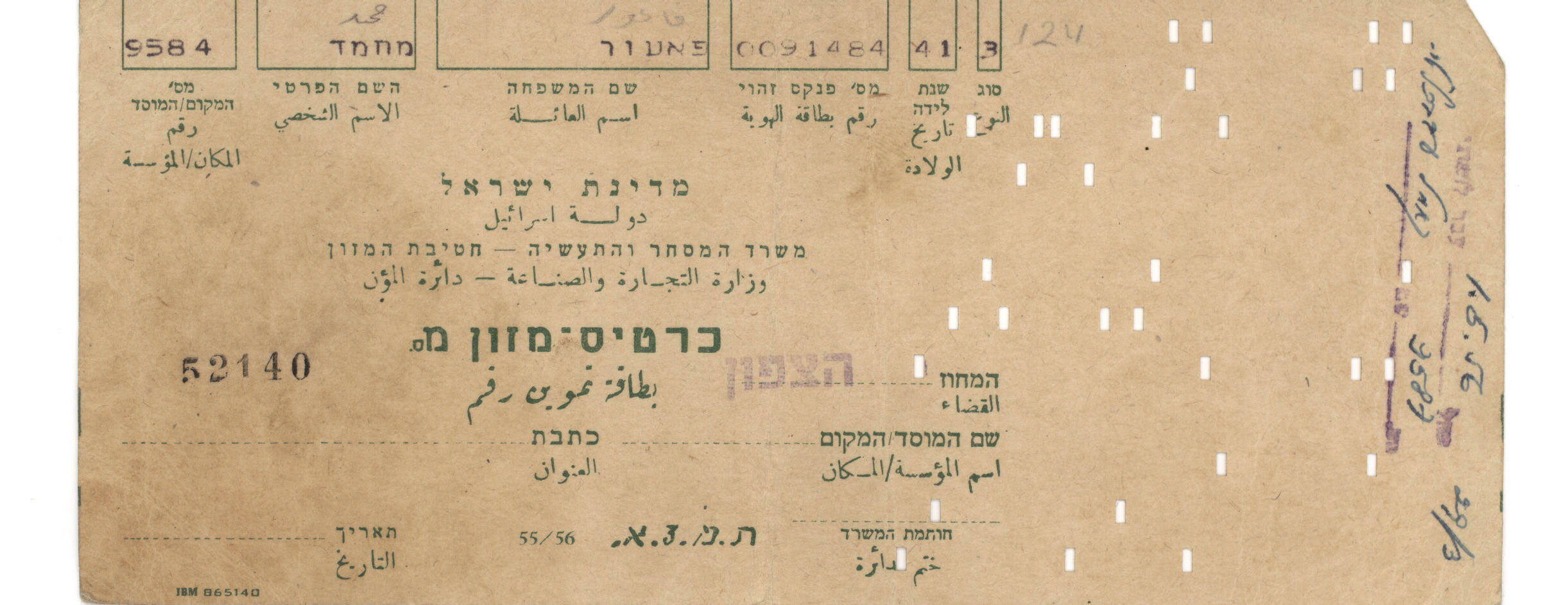

بطاقة تموين تابعه لمحمد فاعور / כרטיס מזון- מוחמד פאעור

مقبرة قرية سبلان / בית הקברות של כפר סבלאן

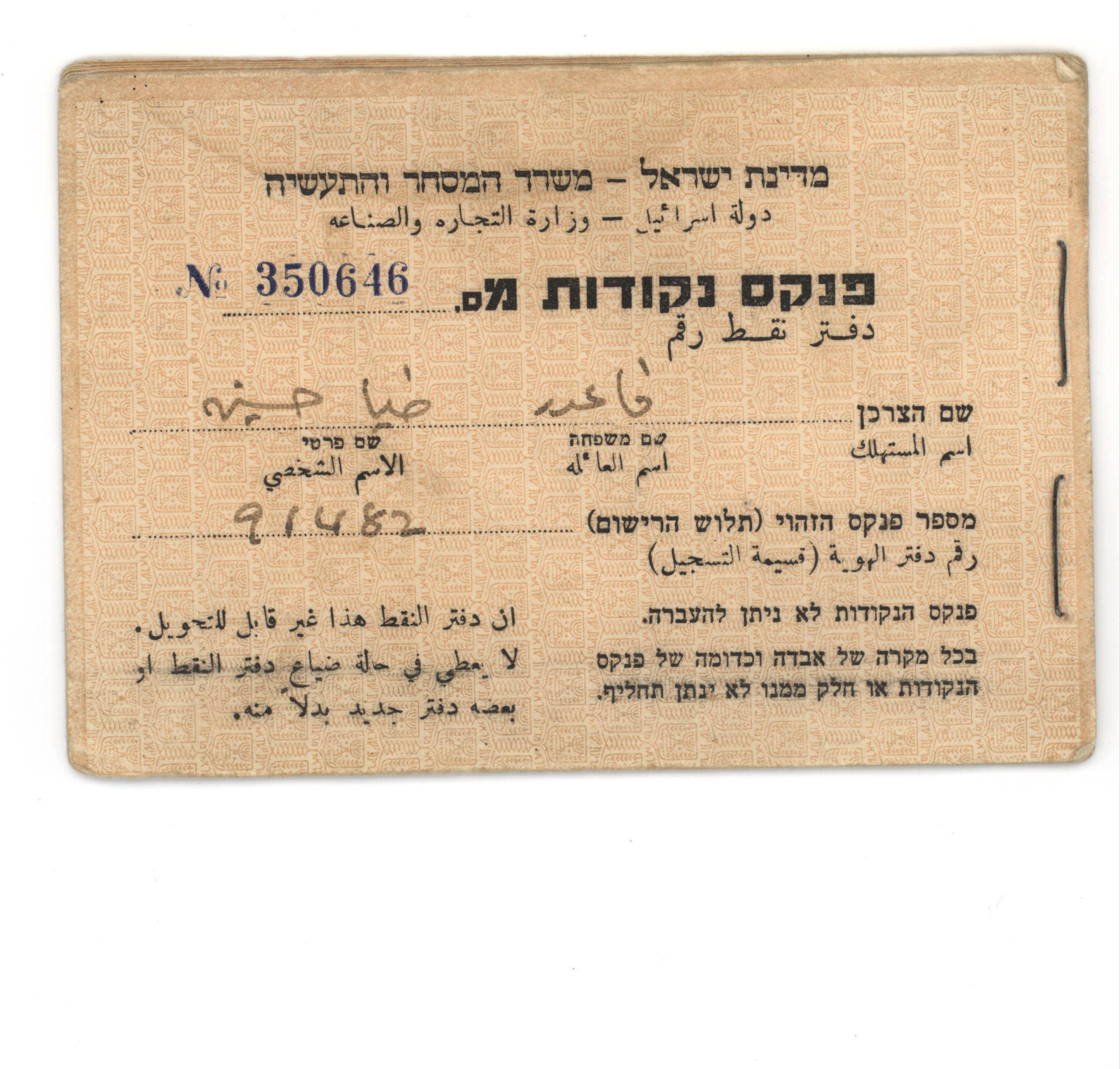

دفتر نقط / פנקס נקודות

بئر تابعة لقرية سبلان / באר ששיכת לכפר סבלאן

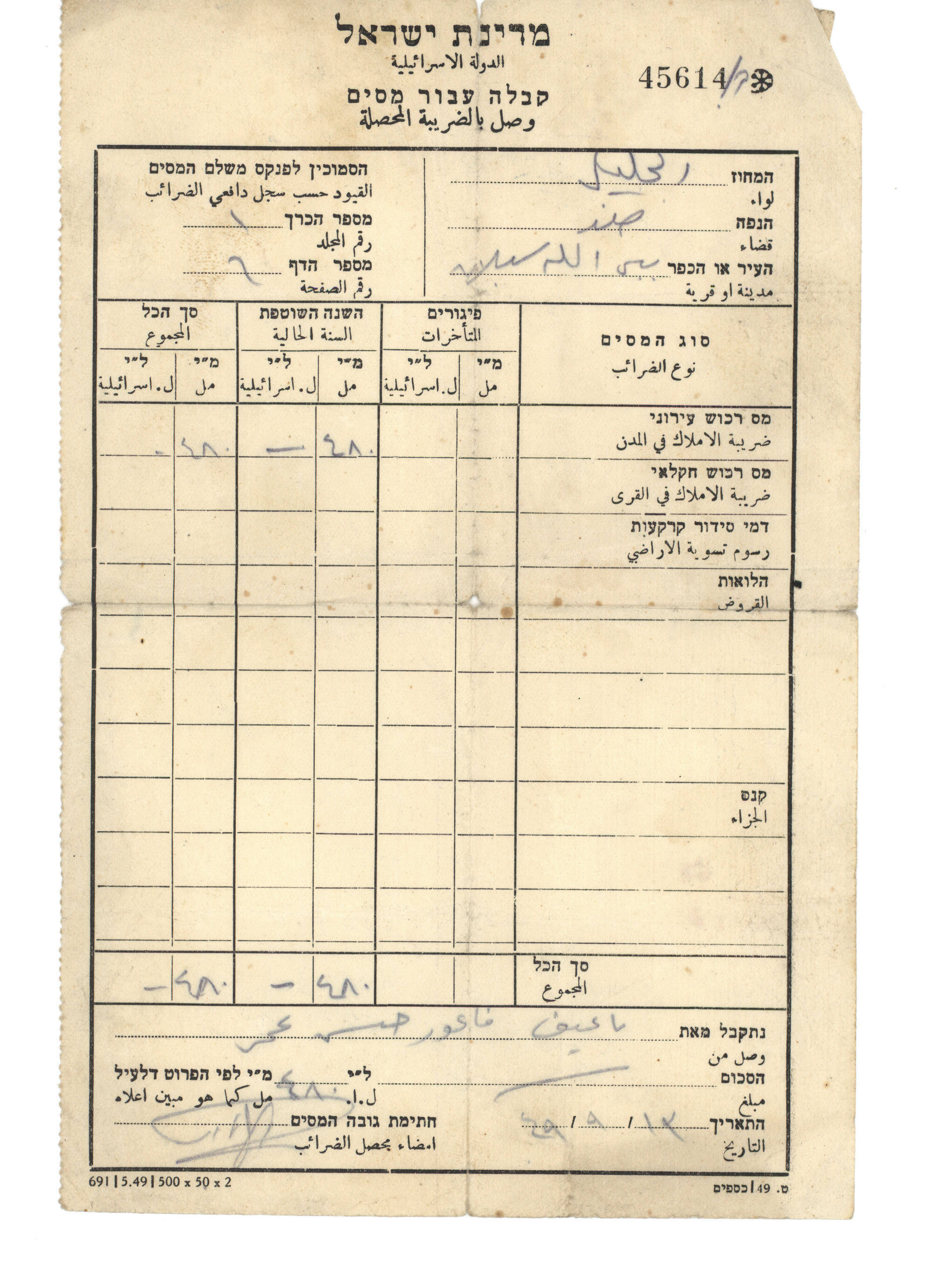

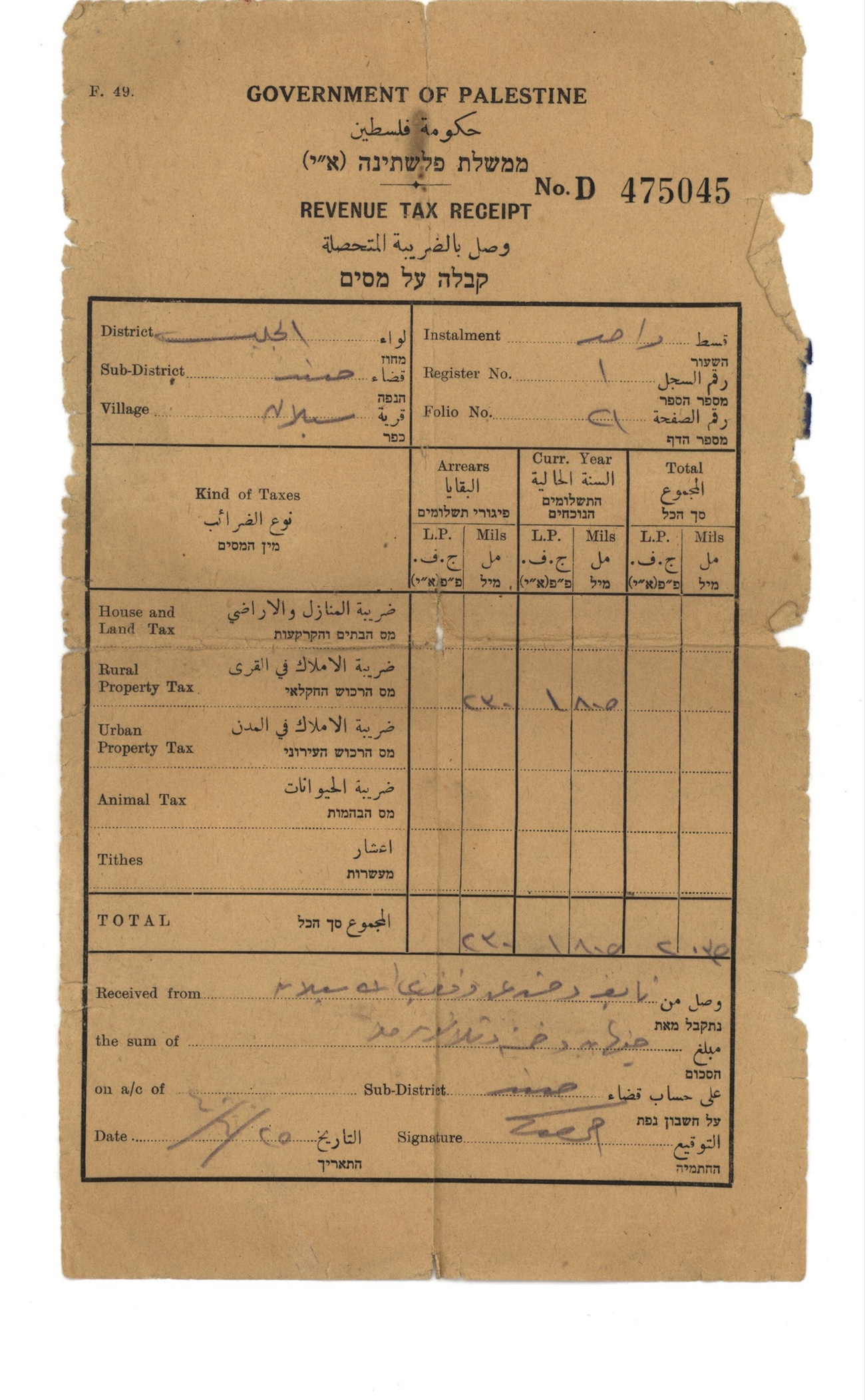

وصل بالضريبة المحصلة / קבלה עבור מסים

وصل بالضريبة المحصلة / קבלה עבור מסים

مقام النبي سبلان / מקאם הנביא סבלאן

مدخل مقام النبي سبلان / דלת הכניסה למקאם

ما اخرجته ضيا فاعور من سبلان / חפצים שהוציאה דיא פאעור מסבלאן

ما اخرجته ضيا فاعور من سبلان / חפצים שהוציאה דיא פאעור מסבלאן

قرية حرفيش المجاورة لسبلان / בתים בכפר חורפיש הסמוך לכפר סבלאן

خارطة قرية سبلان / מפת כפר סבלאן

صالحه فاعور، لاجئة من لبنان / סאלחה פאעור, פליטה בלבנון