Abstract

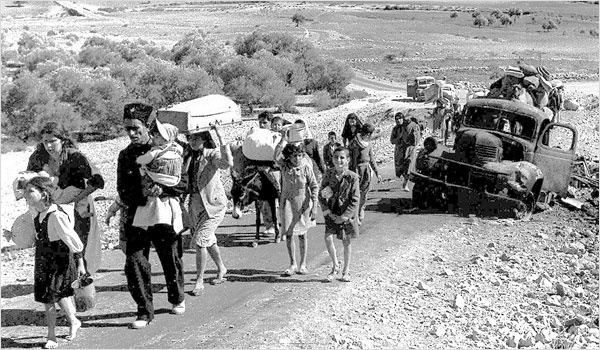

This dissertation investigates the traumatic consequences of the Palestinian Nakba based upon six interviews conducted with Palestinians living within Israel during the summer of 2015. It is the use of a psychoanalytic theory of transgenerational transmission of trauma which describes the effects of trauma on an individual witness and the percussive effects on their children and their children’s children. The focus of this work is studying the path which trauma, from its inception in the events of the Nakba, weaves through the lives of Palestinians and the subsequent effect on their interactions with the external world.

My research on such a phenomenon was motivated by an understanding of the psychological concepts and a deep interest in the persistent crisis facing the Palestinian people. The work is guided by various research questions; what impact has trauma had on the lives of those who experienced the Nakba? Can psychoanalytic concepts enable a deeper understanding of their suffering? Does such a suffering still exert an influence over the lives of contemporary Palestinians and exactly how and to what effect are these influences felt?

The Palestinian Nakba occupies a powerful position in many fields, politics, anthropology, literature, memory work, but is almost totally absent from trauma study. Considering the Nakba’s pivotal position within Palestine’s relationship with Israel a deeper and broader understanding of its position within a wider context is vital. This work builds upon the work of Vamik Volkan and tasks it with understanding the scenario of the Palestinian Nakba. This dissertation takes the personal stories of the lives of Palestinians and puts them into the wider context of the trauma legacies which still carve their unconscious furrows through the Palestinian society of the present.

Chapter 5 \ Conclusion

In investigating the Nakba as a site of trauma, enabled by utilising psychoanalytical theories of transgenerational transmission of trauma, I have explored the pervasive effects of the Nakba on successive generations of Palestinians. Vamik Volkan’s theory elaborates on the means by which trauma features in the relationship between parent and child leading to the child’s inheritance of the trauma legacy. This iterative relationship continues between generations until the trauma is fully mourned but, with the daily traumas Palestinians face from the continuing Nakba, working through trauma is often impossible leading to lengthy and painful trauma legacies. The transmission of trauma through generations also elicits varied ego mechanisms which deal with trauma, which caused pronounced and often aggressive responses to trauma. The effects of such trauma are endemic, and modify the perceptions of the individual who witnessed the trauma and the generations which the witness is progenitor of. The traumatic effects are not only individual but expand to a collective and even national context weaving trauma into the fabric of Palestinian society.

The investigation not only confirmed the classification of the Palestinian Nakba as an incident of trauma but also facilitated the use of the psychoanalytic theory to elaborate on its traumatic features. The analysis was conducted largely within the framework of the model but several features emerged which challenged or added to the theoretical structure. The use of the parent as a means of psychic recovery, in the narrative of MA and NA, presents the corollaries of trauma as more pervasive and cyclical, rather than a purely linear transmission. The experience of SlS and his children indicates the dormancy of trauma within an individual and the inability to transmit trauma without a shared experience of loss. Finally the conflicting dynamics of conscious and unconscious features of trauma in the narrative of GS highlight the prominent role of the conscious elements of trauma and the value in including them into psychoanalytic models, such as that of Volkan. All of these features require further study to confirm and understand, and also invite further study into the Palestinian experience as trauma.

Further study into the effects of trauma into the various events of violence and unrest as corollaries of the Nakba is another avenue of valuable investigation.

Certain elements of Volkan’s model which appear prescient to the study of the Nakba did not appear within the narratives gathered. The phenomenon of ‘time collapse’, commonly found in situations of continuous trauma, was not apparent and further study is needed to understand its absence. I was also unable to identify the characteristics of a perennial mourner within my work, which would be a commonly associated feature of Volkan’s work with the events of the Nakba. It stands to reason that many of the individuals, in passing on their trauma, had at the least begun the mourning process, if not fully completed it.

The study of this nature demands a far greater magnitude of time and research to understand the full scope of Palestinian trauma. My work concerned only a handful of Palestinians living within Israel in a relatively local context. Study into the trauma legacies of Palestinians who live within the West Bank, within Gaza and those who are refugees is vital to gain understanding into the wider impact of trauma. The vastly different social contexts they inhabit and the multiplicity of different narratives will contain huge variants in the trauma suffered and its transmission into successive generations. An expanded temporal element is also necessary to understand trauma legacy. Narratives are constantly situated in the present and the shifting social contexts within which Palestinians live evoke vastly different elements contingent on the external reality and present trauma in entirely new ways. The Nakba is an ongoing process and the trauma which Palestinians face is unrelenting, with each new site of trauma adding to and modifying the experiences of the original site of trauma, the events of 1948. The potential for a wealth of work to be done lies with studying the traumatic effects of the Nakba and its corollaries and this work begins to examine a small section of this field.

The study of the Nakba through the lens of psychoanalysis highlights the deep, unconscious effects that the Nakba has created in the lives of Palestinians today. As opposed to the more wilful act of memory, it is a purely unacknowledged and predominantly undesired legacy which Palestinians carry with them. The fundamental elements of the unconscious which guide daily life remain affected by the Nakba and radically alter the way individuals react to their external environment. In a conflict plagued by violence, the study of trauma allows an understanding of the reactions of Palestinians to the persistent source of trauma, the presence of Israel. The collective effects of trauma also highlight the importance of trauma study. Numerous genocides and vengeful attacks have found their source in incidents of trauma similar to the Nakba, often repressed for many generations they emerge in immense uprisings of anger. It is very possible

that events such as the two Intifadas found their roots in the surreptitious effects of trauma as well as many other conflicts between the Palestine and Israel and many other conflicts to come.

The events of 1948 tore not only into the political, economic, geographical and social fabric of Palestine but also deep into the heart of every Palestinian. The incredibly personal experiences of the Nakba reverberate inside the depths of each Palestinian alive today, emerging only briefly in a silence, a look or a moment of sadness but, when considered collectively, represent a tremendous surge of emotion. It is these emotions which ensure the Nakba will always remain a part of Palestinian history but also as an intimate part of the lives of every Palestinian, as invisible as it is powerful.

Download the full dissertation

Download File