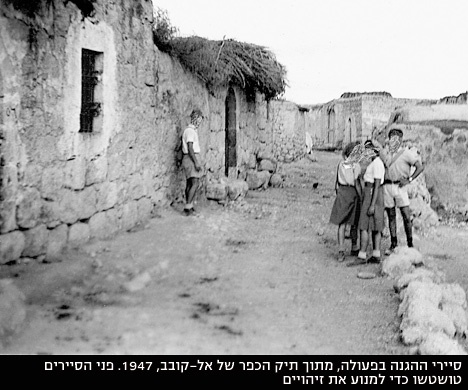

This story begins as a clandestine affair of espionage marked by daring, adventurism, improvisation and imagination as embedded in the official Israeli narrative. In the 1940s, squads of young scouts from the Haganah, the pre-state army and forerunner of the Israel Defense Forces, collected information about the Arab towns and villages in Palestine for intelligence purposes: in preparation for a future conflict and as part of a more general project of creating files of target sites.

The information was usually collected under the guise of a nature lesson aimed at getting to know the country, or for hikes that were common in that period. The scouts systematically built up a database of geographical, topographical and planning information about the villages, which included detailed descriptions of roads, neighborhoods, houses, public buildings, objects, wells, caves, wadis and so forth.

Fighters of Abd al-Kader al-Husseini departing for the battle for Kastel, April 1948.Israel Netach, Palmach Archive

Fighters of Abd al-Kader al-Husseini departing for the battle for Kastel, April 1948.Israel Netach, Palmach Archive

Overall, this intelligence effort was known as the "village files" project, referring to the fact that most of the sites about which information was collected were the Arab villages that existed in Palestine before 1948. The scouts' work included perspective sketches, maps, drawings and photographs of each village and its surroundings. The maps used by the scouts were collected in a secret base on Mapu Street in Tel Aviv, located in a cellar that was given the cover name of the "office of the engineer Meir Rabinowitz" and code-named "the roof."

Detailed information about the villages was meticulously catalogued and organized in files by the planning bureau of the Haganah general staff and held in the organization's territorial commands around the country. Greater boldness and courage were required when the Haganah commanders decided to photograph the villages from the air in order to broaden the information that existed in the files. Sophisticated ruses were used to deceive the British authorities, who forbade such activity. The villages were photographed under the guise of the activities of a flying club or romantic aerial excursions; the camera and negatives were hidden in and around the plane. Innovative means were developed to collect information secretly. Women played a significant role in this process, and one of them became, as far as is known, the first female aerial photographer of the Yishuv, or Jewish community of Palestine.

Personnel from Shai, the Haganah's information service, and afterward Arab informers as well, collected detailed and extensive information - historical, social, economic, demographic, educational, agricultural, military, architectural, planning and more - about the villages from the beginning of the 1940s. Based on this information, textual surveys of the Arab settlements were compiled. Over the years, many such surveys were conducted, covering the country thoroughly.

Yet the products of this historical national project also bear the potential to create an alternative narrative today. They can challenge official history - based on original, official materials. Doing this also requires resilience and boldness, but of a very different kind than what was needed back then.

Read the full article at Haaretz website