A book always makes a statement. Whether it’s resting on the table or visible on a shelf, it’s making a statement – cultural, political, or both. Space, on the other hand, represented by maps, hiking trails, signs, is usually viewed as something objective. Neutral. Not subordinated to social, historical or other forms of power.

“Once Upon a Land,” published by Zochrot and Pardes, is a guidebook that shows the spatial consequences of power, attempts to undermine the neutrality of space, to expose the silenced dimension of our reality. It reveals that the neutrality is only apparent, demonstrates the degree to which our space is the product of design and control guided by unequal national forces. The curious hiker who follows its recommended routes will discover that space has been continually mobilized in a struggle to create a hegemonic account of Israeli society as characterized by generations of Jewish settlement, like the history and civics textbooks published by the Ministry of Education tell us. The guidebook exposes how space has been designed in a way that silences dozens and hundreds of Palestinian stories, and thereby serves as an additional means to create a Jewish collective consciousness at the expense of Palestinian society.

The book offers 18 tour routes, from Zib (Achziv) in the north to Bir Saba’ (Beer Sheva) in the south. It is bilingual – Hebrew and Arabic – laid out in such a manner that the text flows easily and continuously in either language. And thus, by providing a resource that in any other context would be viewed as legitimate and non-threatening, it offers readers tour routes which enable them to slowly learn the story of Palestine. Is this a denial of Zionism? Can it co-exist with Zionism? How threatening can this awareness be to Israeli tourists? I wonder.

One would think the question is a personal one, depending on the particular individual. But, since that story has been silenced at the national level, I’m afraid the Israeli campaign against the possibility of telling an alternative story, or a parallel story, will frighten many people, and I already imagine how future hikers would hesitate to page through the book, feeling like traitors if they did.

I was surprised to find that even Amal Eqeiq, whose afterword to the book, “Not the final word,” wonders about the book’s emotional effect on Jewish-Israelis, and what political experience it will provide them: “At the end of the day, a Nakba tour requires a critical imagination and soul-searching with respect to the question of my own relationship to national identity. The tour also requires taking an ethical and moral stance with respect to the past and the future. How many Israelis will be willing to make the necessary effort – personal, social, intellectual – especially on a weekend?” But she also notes that “the reference to the Palestinian past and its recognition also reflects the Jewish moral obligation to justice and reconciliation.”

I expected a standard guidebook that would lead me through familiar sites to tell an unfamiliar story, among trees, along trails and alongside the ruins of a period no one mentions, at least not in Hebrew. I found an amazing educational resource for creating a dialogue to open up a reality which, were we able to recognize it, as well as able to recognize Israel’s current reality for what it is, could help us create a new discourse, one that involved more listening and less haggling.

I must admit that I haven’t yet hiked the routes in the book. But it reads fluently. It’s focused, easy to understand, and in addition to the tour routes provides demographic data about the Palestinian villages that were there until 1948: notes; and also information about the law, the historical background and the current situation, as well as specific directions about how to reach each location and guides to the tour routes.

It’s hard for me to remain indifferent to descriptions, even when presented neutrally like in any other guidebook. The very act of exposing hidden layers gives rise to simultaneous emotions of understanding, pain and anger. That’s true in the first tour, to discover Zib, which starts at the place that’s known today at the Achziv National Park, where I found myself again aghast when I read the description of the neglected cemetery - especially because I’m someone who makes an effort, when travelling abroad, to visit Jewish cemeteries, and who expects to find them cared for, to be able to read the names of the deceased on the gravestones and the circumstances of their death, as well as the lovely memorial texts each family chose for its loved one.

Nor do the tours ignore the Zionist military operations in 1948, exposing the tensions that were present from the early days of the Yishuv with respect to the Palestinian communities that lived here - because of the struggle over the land. A struggle that continues today, one that created and continues to create a one-sided national discourse that doesn’t recognize the distress of the inhabitants of Palestine during that time, who have been “absent” since then for decades in their own land or refugees in neighboring countries.

Deconstructing the balance of power into relations of the type we’re familiar with also occurs in the sources from which the guidebook draws. They’re varied, including interviews, books, articles and testimonies from internet sites. That variety also says something significant to me as a reader who’s used to official sources that are considered to be authoritative. Suddenly I’m exposed to the personal stories and testimonies gathered from interviews and internet sites, which now also become important, provide firm evidence.

History, as we know, is written by the victors. It’s never an objective account. That’s why the task Zochrot undertook – to create a guidebook that will bring to life Palestinian history in the pages of the book as well as by making me walk along its tour routes – is more than a fantastic story: it’s an important milestone, an honest effort that enables me to hear another account of what used to be here until 1948, and still exists today in the hearts of millions in the Middle East and throughout the world.

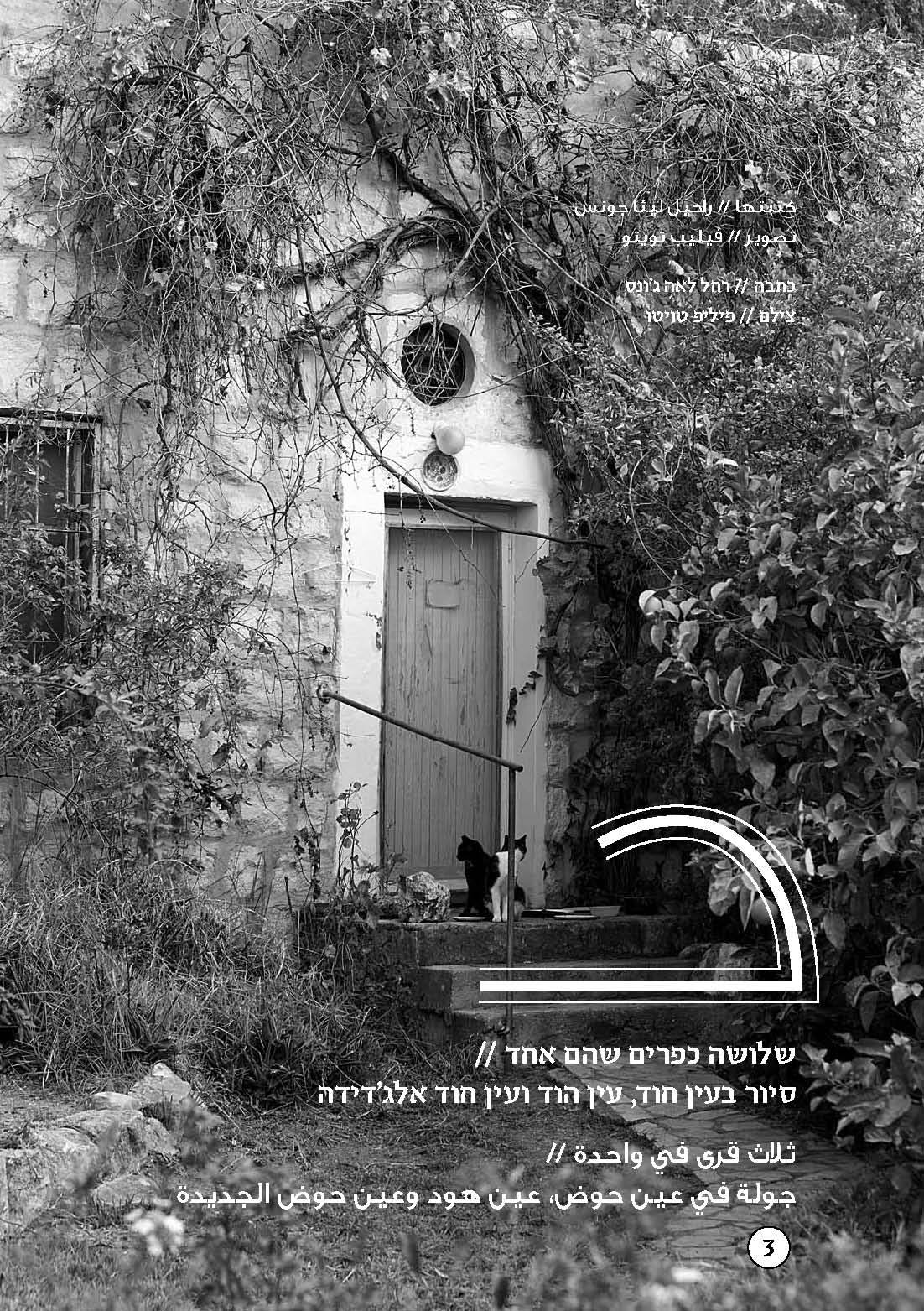

But, to balance my critical appreciation for the fact of the guidebook, let me note that the Hebrew proofreading (I don’t know Arabic) leaves much to be desired with respect to spelling errors, phrasing and excessive detail on some of the routes. These shortcomings, however, fade to insignificance in comparison with the content provided. It’s a breath of fresh air, interesting, challenging and serves as an additional way of reexamining our reality. As Rachel Leah Jones writes in the tour of Ayn Hawd, Ein Hod and Ayn Hawd al-Jadida: “We’ll put on bifocals that will show us all of history’s contradictory layers. We don’t want to see only what used to exist and make believe it’s possible to ignore the present. Bifocal vision means seeing Israel/Palestine simultaneously: just like Israel/Palestine, what appears to be beautiful is very beautiful – and also extremely ugly; very sweet and also terribly bitter. There are many ways of approaching this reality, and this is only one of them.”

I warmly recommend it.

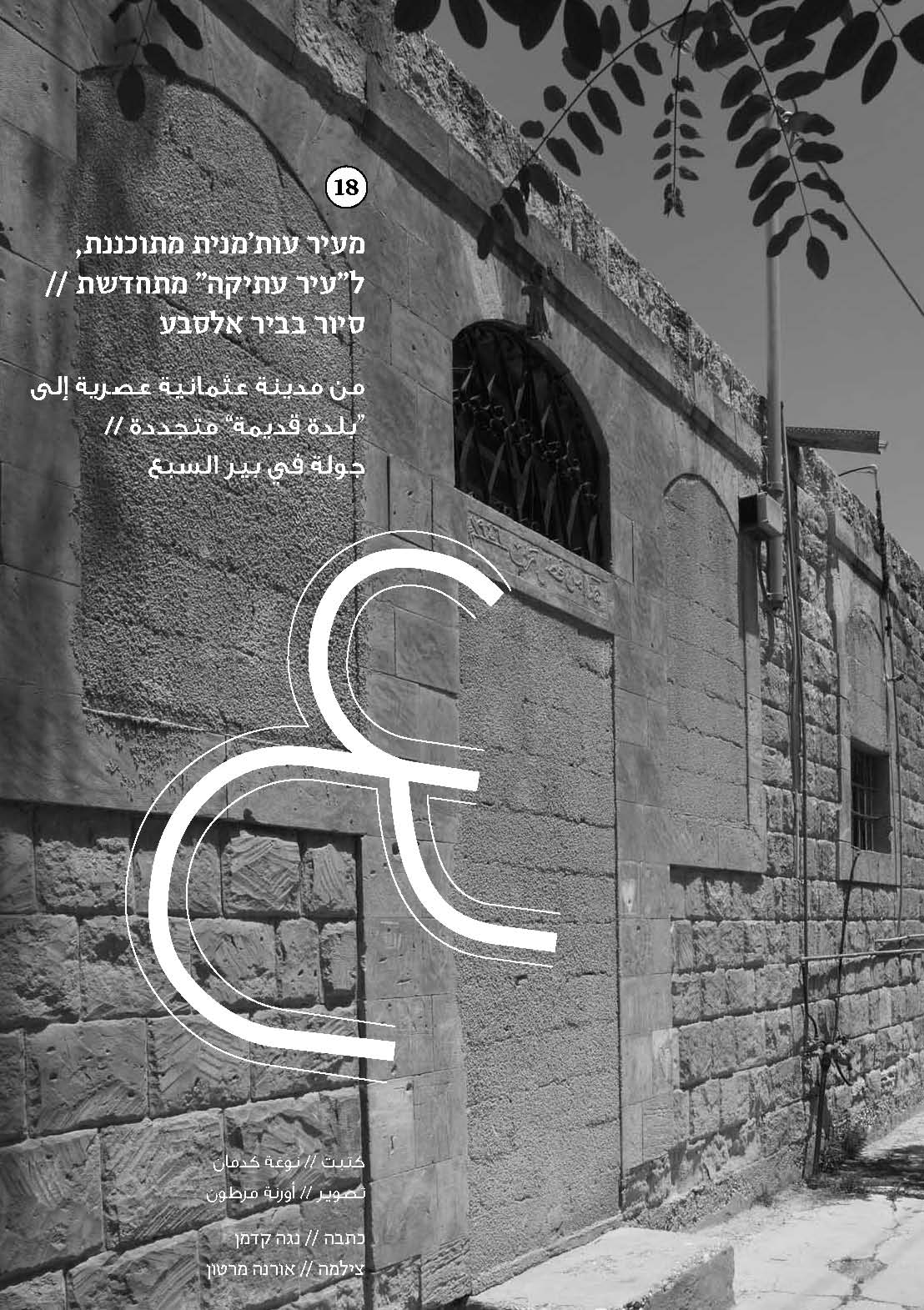

סיור בביר אלסבע / אומרים ישנה ארץ // جولة في بير السبع / حكاية بلد

סיור בעין חוד, עין הוד ועין חוד אלג’דידה / אומרים ישנה ארץ / جولة في عين حوض، عين هود وعين حوض الجديدة / حكاية بلد

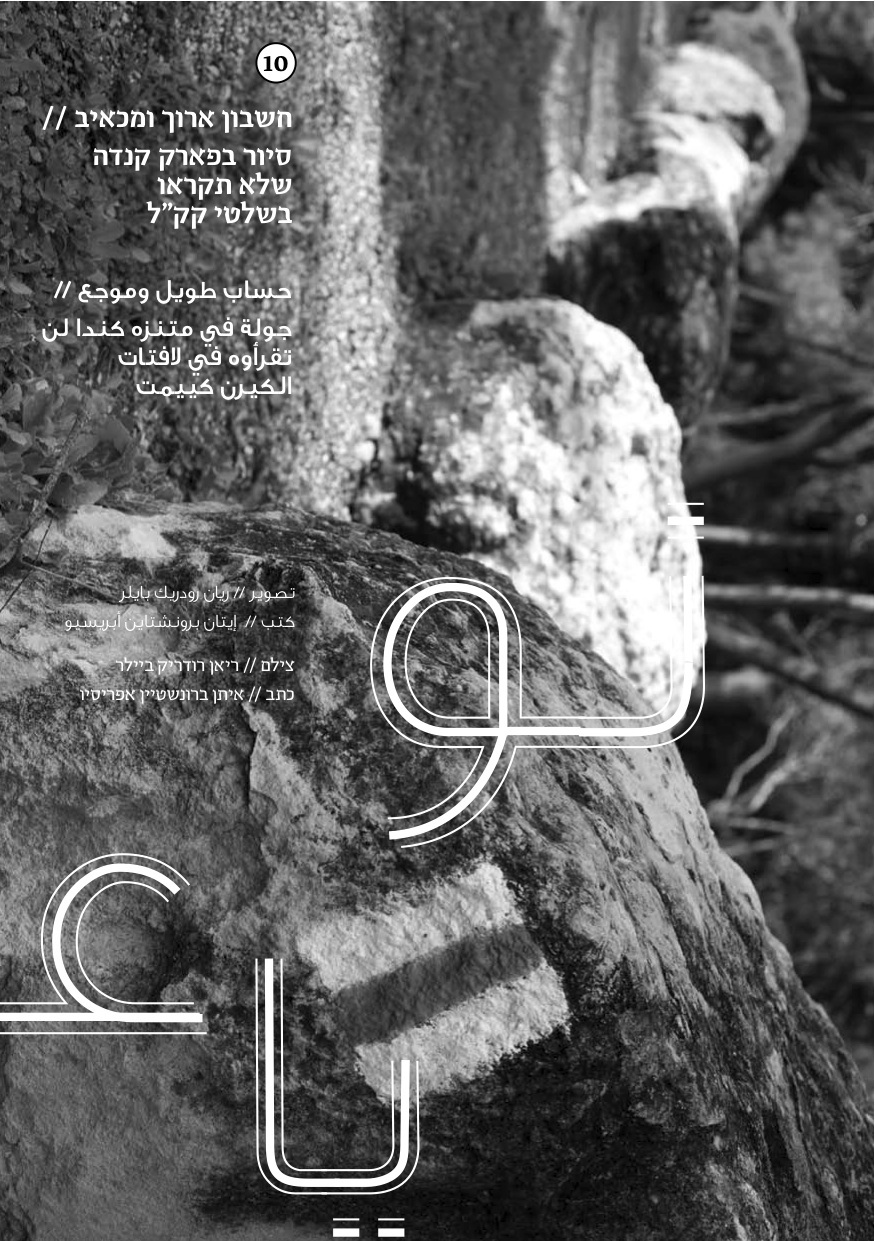

סיור בפארק קנדה / אומרים ישנה ארץ // جولة في متنزه كندا / حكاية بلد

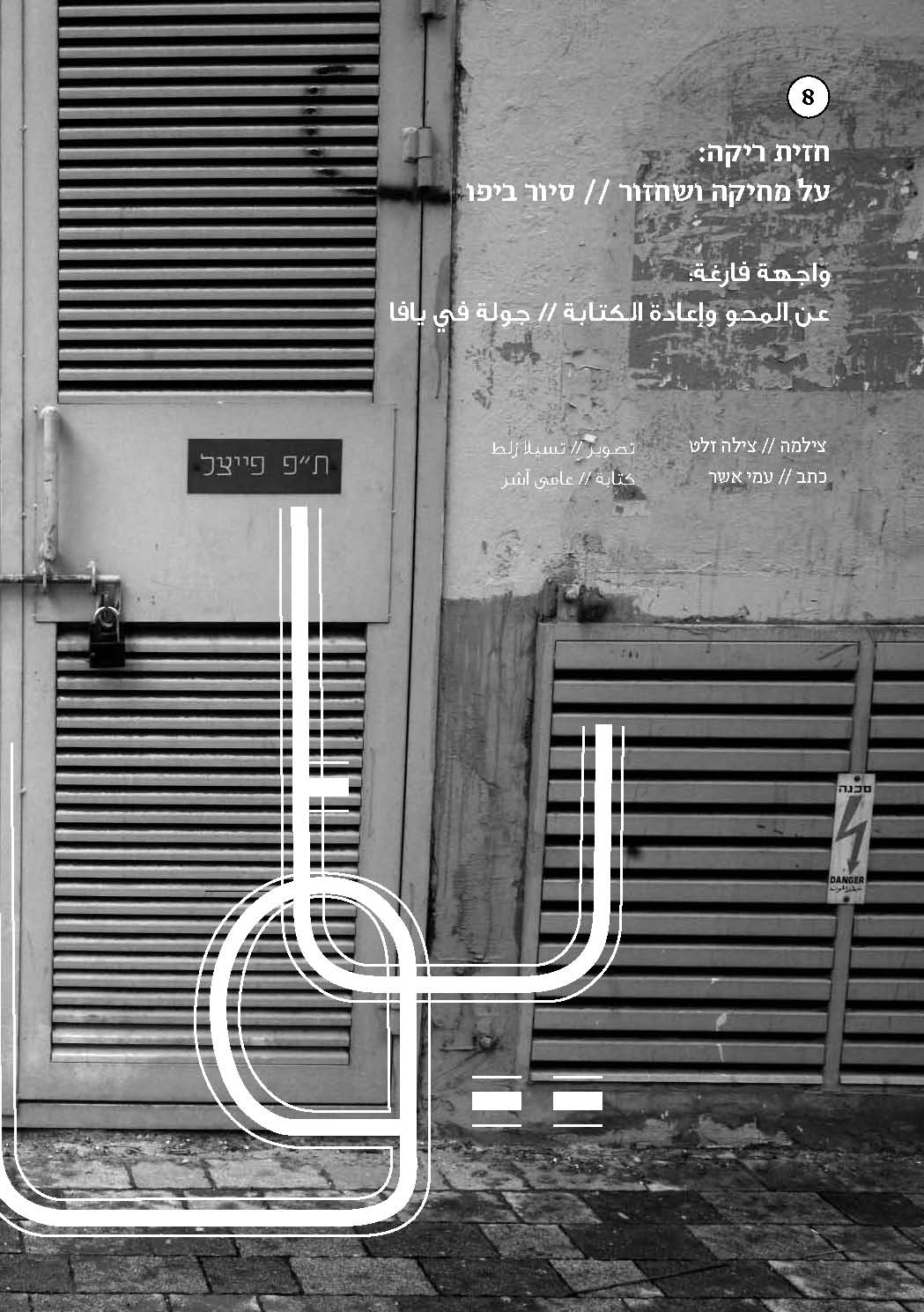

סיור ביפו / אומרים ישנה ארץ // جولة في يافا / حكاية بلد

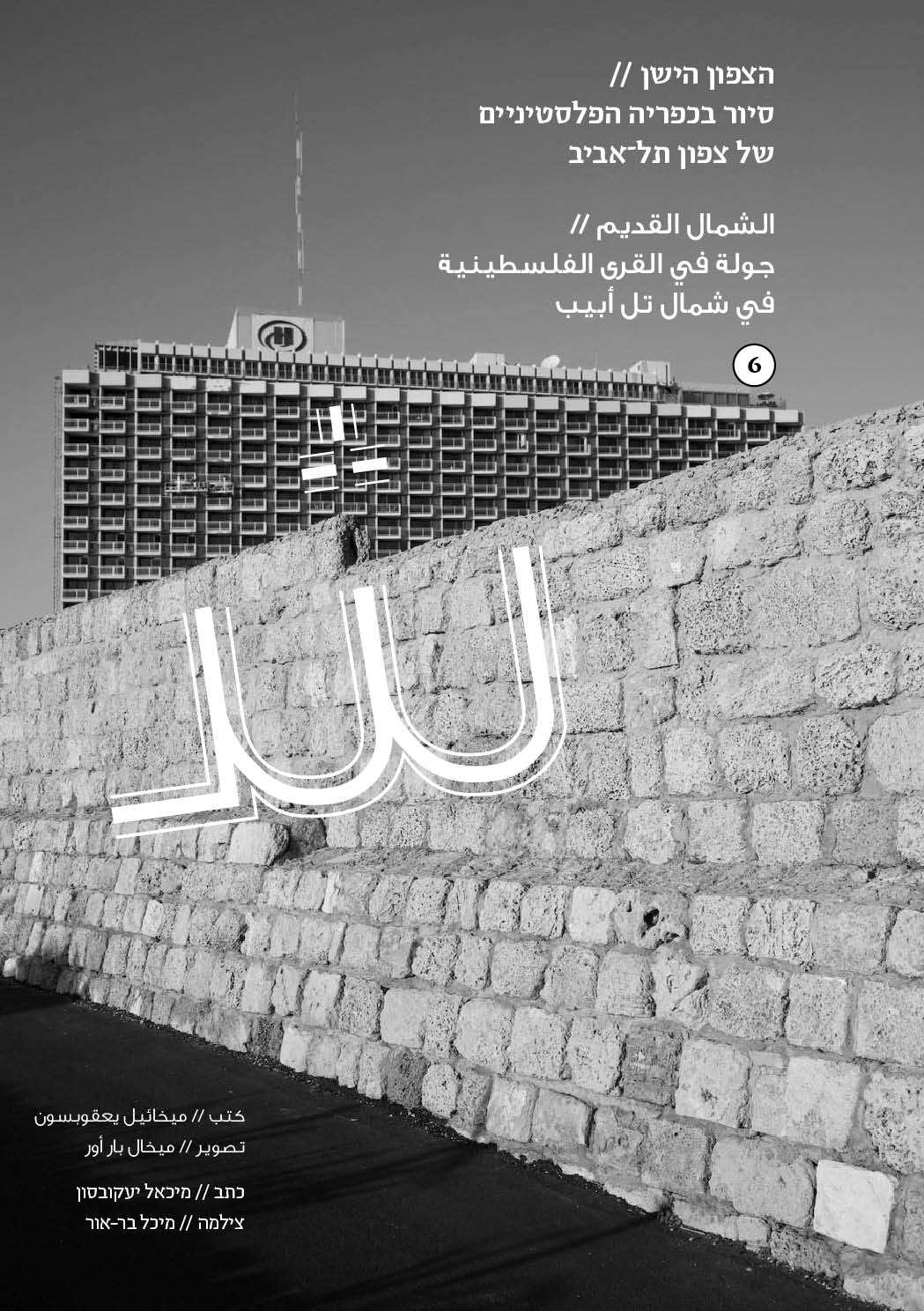

סיור בכפריה הפלסטיניים של צפון תל־אביב / אומרים ישנה ארץ / جولة في القرى الفلسطينية في شمال تل أبيب / حكاية بلد

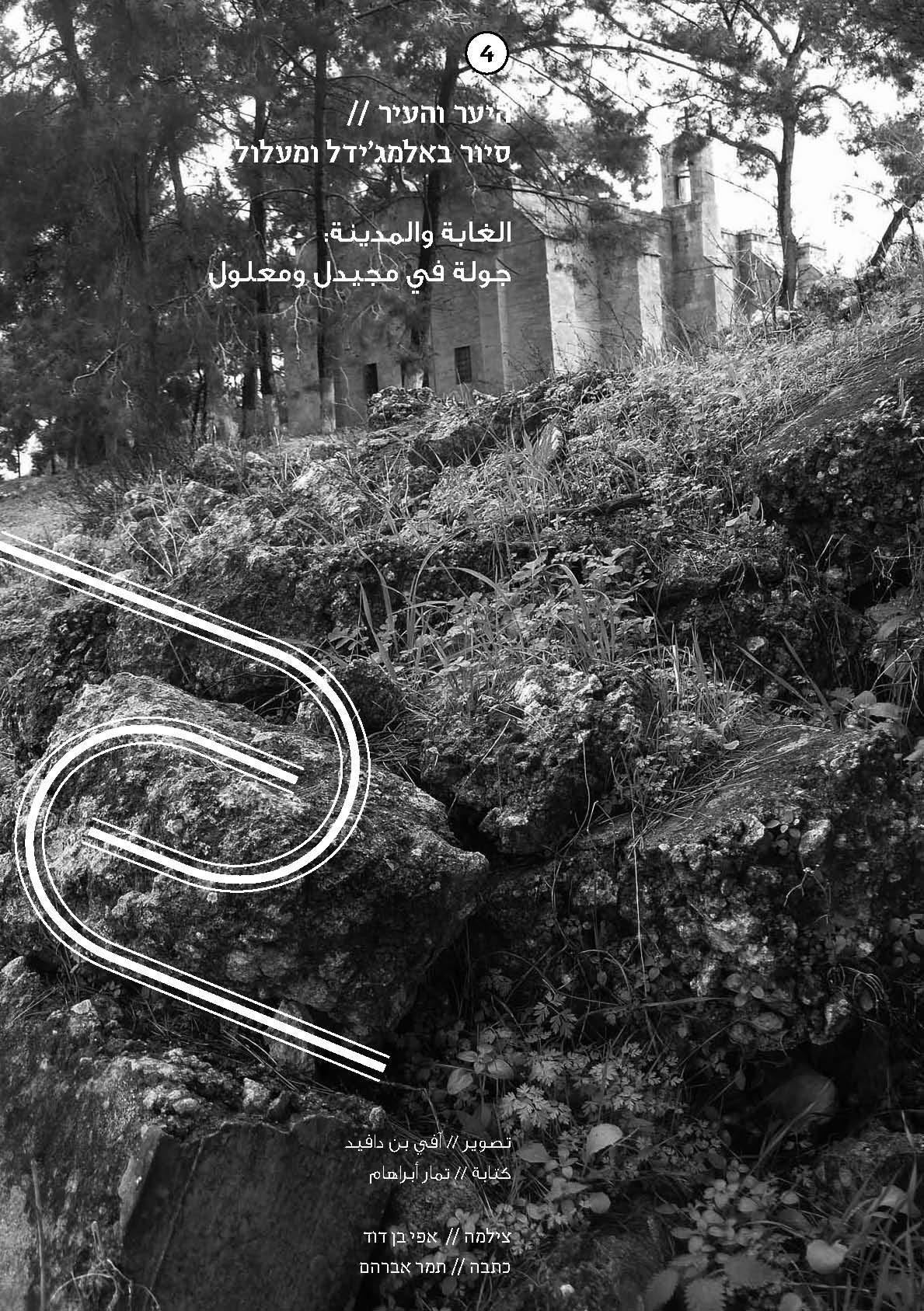

סיור באלמג’ידל ומעלול / אומרים ישנה ארץ // جولة في مجيدل ومعلول / حكاية بلد

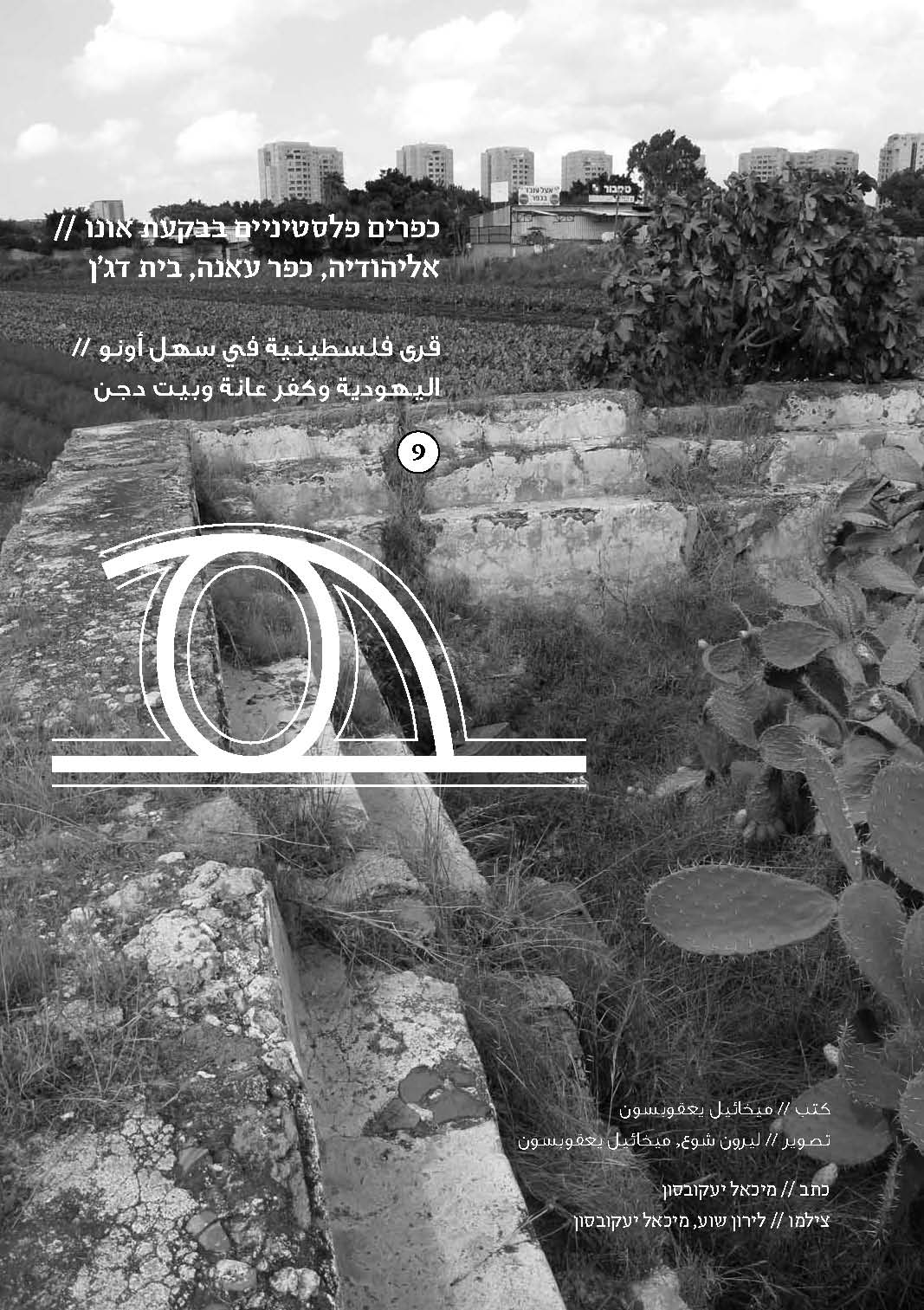

סיור לכפרים פלסטיניים בבקעת אונו / אומרים ישנה ארץ // قرى فلسطينية في سهل أونو / حكاية بلد