“Bibi’s House.” A project by Gil Muallem Doron

A discussion evening at Zochrot as part of the exhibit, “Toward the return of Palestinian refugees,” 1/12/2011

Transcribed by Noa Schindlinger

Eitan: This evening’s discussion is being held in conjunction with the exhibit, “Toward the return of Palestinian refugees,” which considers planning alternatives for the return of Palestinian refugees. The “Bibi’s House” project fits this context very well.

Gil: The project is named after the Bibi family, who lived in Jaffa in the building that until recently housed the Arab Democratic School. We worked with the pupils on the history of the built environment – the location, the house, the surroundings. We focused on the Manshiyya neighborhood and on the Bibi family home at 13 Gaza Street. In essence, I worked on the project with two different groups: Arab pupils from Jaffa and Jewish students from an institution which prefers not to be identified. When the project was exhibited we were forbidden to identify the academic institution in which I worked, because it didn’t wish to be associated with this project. In the past I worked with the Weizmann School, a community from Jesse Cohen in Holon and in Gan Meir. This particular course was unusual because no community existed, nor was there any contact with the Bibi family, some of whose members are in Amman and others in the United States. The project faced many difficulties. We worked with the Rabita in Jaffa, but all our efforts to contact the Palestinian family were unsuccessful. We wanted to interview Walid Bibi, the grandson, in Amman, but were unable to do so; they didn’t get back to us. As far as he’s concerned, he’ll return to Palestine only when Israel is wiped off the map. That’s what he says in a video on the web site, www.palestineremembered.com. We finally were able to contact him the day before the exhibit opened and interviewed him from Jordan. He spoke with the pupils; it was too hard for me – I dropped out of the conversation.

The students were assigned the task of redesigning the building for the Bibi family who returns to inhabit it. I didn’t specify how many family members are coming back. The project is personal, abstract. They saw photos of the family and of where they live. I don’t know how many great-grandchildren there are. The grandson has a son in the United States, but we weren’t in contact with him. It’s an architecture and design studio; the idea was to prepare a redesign that would return it to the family. When the family last lived there, the building was in the Arab style, surrounded by citrus groves. The students had to decide who’d live in the house – only Walid Bibi and his wife, or the whole extended family.

The project with the Arab school, where I was employed as an artist/teacher, focused on the Manshiyya neighborhood and the house at 13 Gaza Street.

Walid Bibi says they had another house in Manshiyya, bordering the Jewish neighborhood. That’s why we selected it, and also because it had been completely destroyed.

The building has a sign placed there by the Rabita School – it had a high school when it started but later remained a primary school, and closed this year (another indication that the nakba continues today). Its orientation was Palestinian, even though it was funded by the Ministry of Education.

I filmed on the day the school closed. One of the girls can be seen reading the Arabic sign on the wall of the school. The film is unedited. The next segment is symbolic both of what the students did and of what the pupils and I went through personally. The segment is called Recite (Re-site). We filmed it at the Ottoman railway station. There had originally been a sign there which read, “Manshiyya,” but when we arrived it had already been changed to “HaTahana” [The Station]. You see a child’s drawing of a typical neighborhood house. We intended to copy it in chalk on the sidewalk. The person in charge of the parking lot didn’t allow us to make the drawing. We argued, but he refused, even though the chalk would wash away in the rain. He said he’s sympathetic to the issue, but was afraid the chalk would get the parking lot dirty. One of the pupils had a grandmother from Manshiyya, but the person in charge of the parking lot was worried that it would get dirty. He decided to call a municipal inspector, but the pupils insisted on continuing to draw. The inspector didn’t arrive. We repeated this activity one other time. The pupils are singing a song that appears on the Rabita page, about the return to Yafa and memories of the town.

[He now presents the students’ work and the catalogue, which appears only in virtual form because there was no money to print it.]

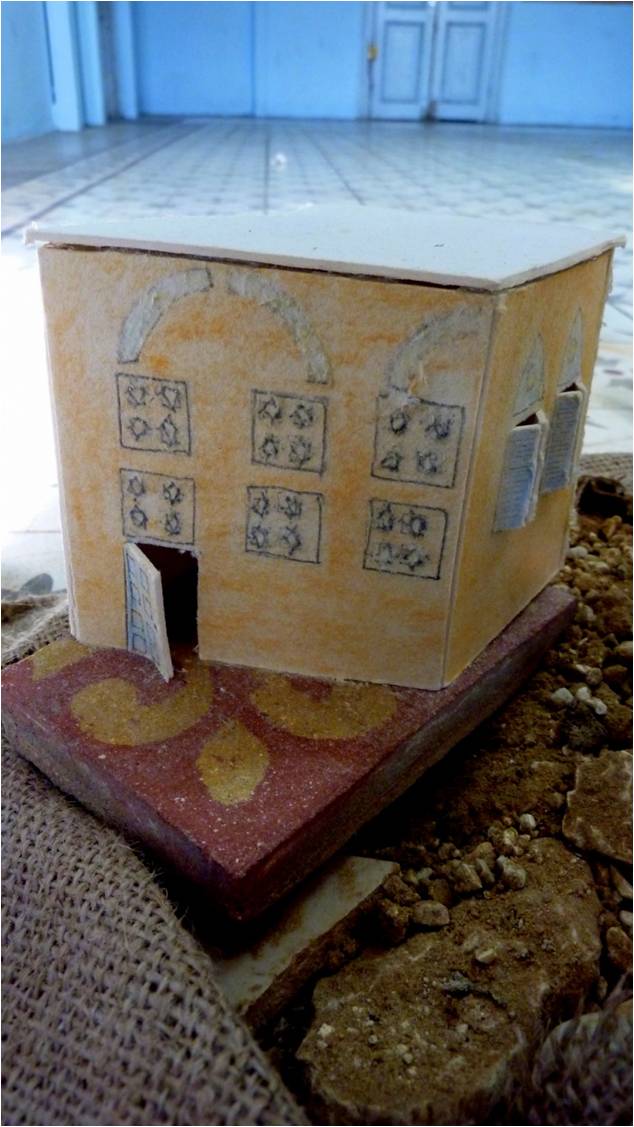

We did a number of things: a tour of the Jaffa escarpment and Manshiyya’s oceanfront, collecting fragments of floor tiles and incorporating them in models of the buildings. We learned about Moslem architecture, and compared it to other cities. Works using sand from Manshiyya, in sacks – in the central room of the house, the diwan – torn sacks, the sand spilling from them; a motif recalling Tel Aviv, growing from the dunes. A work called “We returned to the land, to build it and to be rebuilt,” which of course echoes the Zionist song, “We have come to the land…” [Anu banu artza…] The models were constructed jointly by the pupils and the students.

The pupils prepared the house for the refugees’ return by combining art with design - for example, by updating the Moslem architectural domed roof. We also touched on the present. There was a Palestine conference, at which pupils were asked to draw Jaffa and send the pictures to other places in the world. I chose not to participate in re-drawing Jaffa’s familiar iconic images, such as the clock tower, the Mahmudiyya mosque, etc. The pupils have a stronger connection to the Daka orchard, expulsion orders, open sewage, etc, because that’s part of their own Jaffa experience. The exhibit also included portions of the interview with Walid Bibi, whose voice sounded from the walls. Because of the title, “Bibi’s House,” almost 700 people came one weekend, as part of the “Open House” tour, 80% of whom had no idea what they were coming to see, didn’t understand why they wound up at an Arab school, with texts in Arabic, etc. The pupils had to serve as guides. It wasn’t actually uncomfortable; there were a few comments like “What’s the nakba,” etc, and the principal had to explain that his lands had also been expropriated. In other words, the historical discussion became relevant to today because of the experiences of those involved.

There had been an attack in Jerusalem on one of the days we were meeting; it was difficult to continue because some of the pupils were afraid to come.

[He shows photographs the pupils took. They were displayed as if in a demonstration, signs placed on bricks.]

We used Zochrot’s booklets about Manshiyya – like guerillas, we displayed the texts throughout Manshiyya and asked people what they knew about Manshiyya. We had some difficult experiences.

A studio project on community architecture – a refugee family returning home, displaying its history in the gallery – moving from the private to the public space.

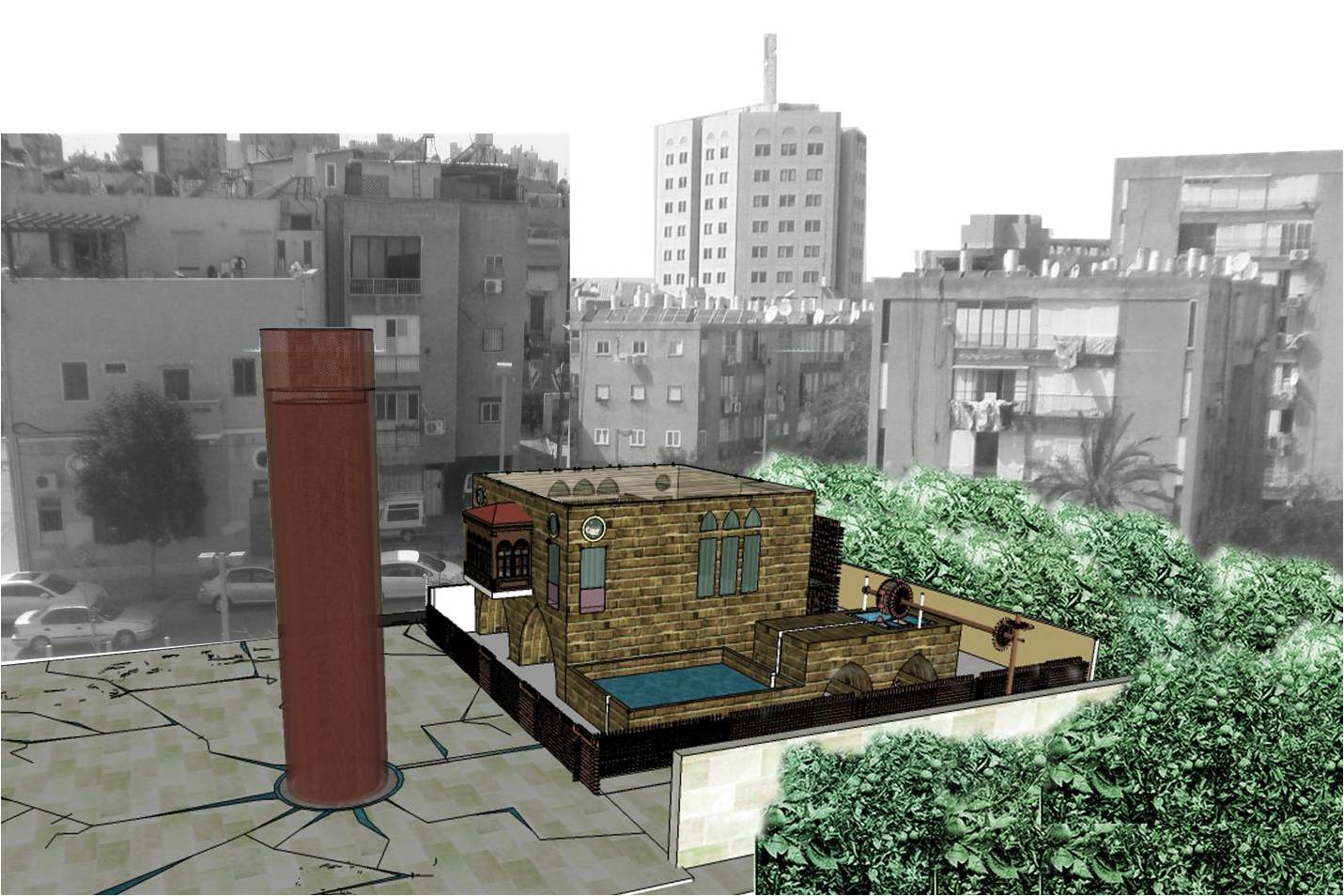

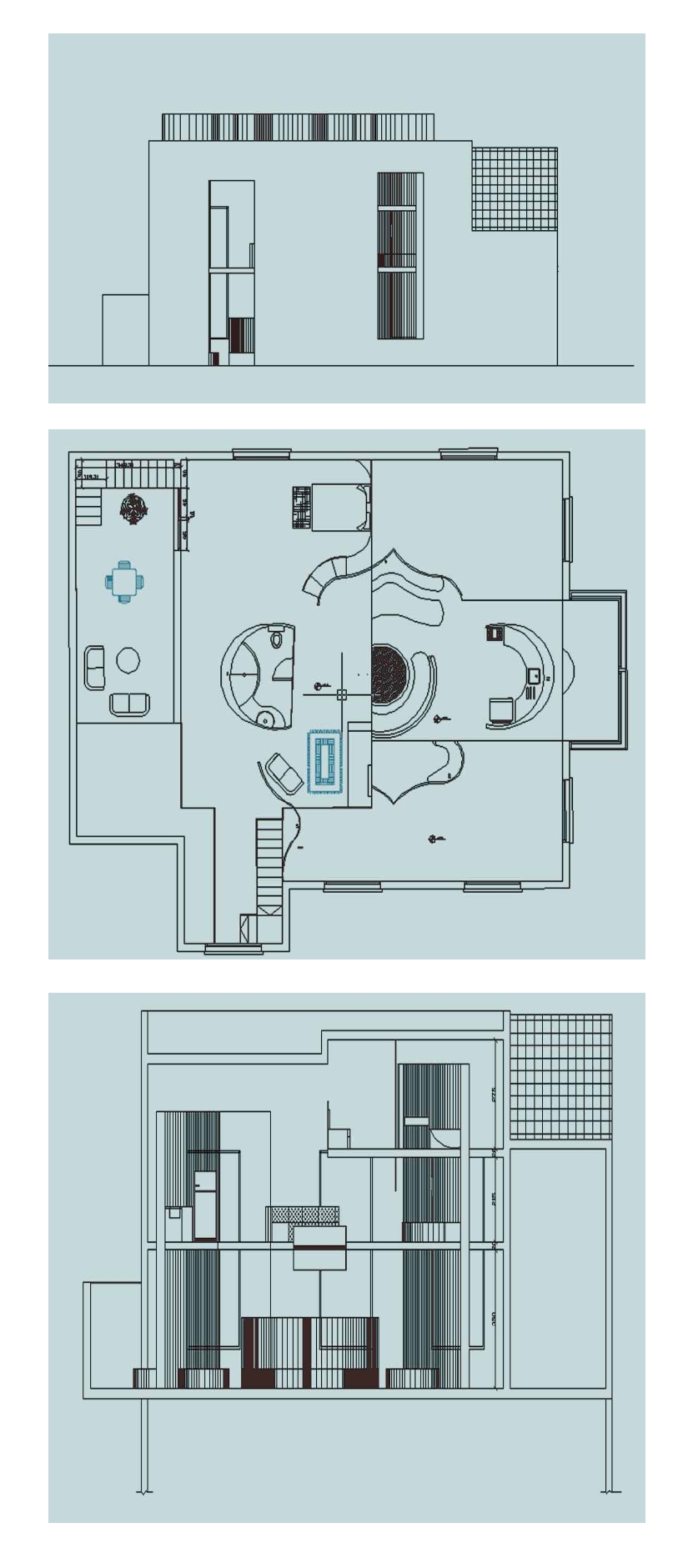

Adi Cohen’s project – “Antiliya”. Adi explains her design for a home for the grandparents, parents and two children. She retained the original structure, without the additions for the school. There had been a well and cistern, over which classrooms had been built. I uncovered what had been there in the past, what had been visible – the texture, the kurkar (sedimentary sandstone rock), the antiliya (a loop of rope or chain with buckets attached for drawing water). The gallery was inspired by the minaret – both because it’s part of the culture, and it’s also tall and noticeable, drawing people toward it, in the middle of today’s plaza. It’s surrounded by a fence one can look through and see how the water is drawn from the well, connecting what’s outside and what’s within – a wheel that people can turn and see the process, an underground passage with pictures on the walls – that’s the gallery. The passage leads to the minaret’s entrance; one ascends in a spiral, slowly, the sound of the family’s voices in the background – a link to the family. You can’t see outside as you ascend because the tower’s wall is solid, but when you reach the top you’re able to look out over Jaffa. The tunnel shows what Jaffa used to look like, and the tower provides a view of Jaffa today. The original structure had a porch overlooking Gaza Street. I moved it to face the plaza with the minaret, a place for the family to watch people arriving.

Gil: You decided that the entire extended family returns, and, in principle, you recreated the building’s traditional appearance, inside as well, even though you knew that other students made different choices

Adi: Arab houses usually have a central space, most people live in extended families, communally, and that’s the atmosphere I thought they’d want when they return, a feeling of how things used to be.

Gil: The return of refugees is theoretical, but it’s imagined in personal terms. We refrained from talking about it because the other teacher who worked with me is a leftist who didn’t want to appear here today, nor did he want us to mention his name because he was afraid of what might happen at his job. The students were very brave; they agreed that their names would appear on the invitation. I decided not to include them, to protect them. The educational institution whose name can’t be mentioned decided, after the project was ready, not to display it, and I insisted we had an obligation to do so. The compromise was to omit the school’s name, and agree that it was apolitical. The official excuse was that you can’t display works by pupils together with works by students. I was ordered to display the works without including the institution’s name so the Ministry of Education won’t stop funding them, particularly because of the current nationalistic political atmosphere.

Adi: The balcony facing the plaza is supposed to provide a view, but also privacy. The plaza’s pavement has blemishes and fissures, symbolizing the water channels that existed when there were citrus groves here that received water from the antiliya. The cracks in the pavement connect the minaret to the house. The past cleaves the pavement

Gil: The family maintains its privacy, but after the return they’ll be in the public eye.

Shahar Deklo’s project: A completely different approach, less of a connection to the family. He links the house to its actual surroundings, begins with children playing soccer – something that has always united Jaffa’s Arabs and Jews – and continues by enveloping the area with shapes and forms: Arafat’s kaffiyeh shadowing the soccer field, a tent as an abstract symbol of wandering. Here, too, the balcony was moved from Gaza Street because there was a building across the road, so that it could overlook a more public area. It’s chaotic within – the triangles that were outside have come in; it’s hard to imagine a family living like this, even though there’s still a diwan. The triangles represent frozen fragments of time, the family’s public aspect, though the external affects what’s within.

Sivan Tfiro’s project: A nuclear family, father, mother and adolescent son. They own a restaurant. The building undergoes a mutation, is stretched upward, a lattice motif – a lattice screen (mashrabiyya) allowing women to look out without being seen. We constantly talked about how public the family would be, and who’ll visit the gallery. Here you can be in the plaza and also come inside. She found it hard because of her background – she’s from an orthodox Jewish family.

Ma’ayan’s project: I was also inspired by the mashrabiyya, which I dismantled to create living spaces. Walid Bibi and his wife will live in the house, on the upper story, and manage the gallery. The idea is for people to walk through the house and learn its history, look down through the mashrabiyya without disturbing the family. I created horizontal openings so people could see inside – both visitors and family members. I knew not all family members would return, and wanted someone who nevertheless wanted to come, even now, to represent the family. The openings are intended to create interest in the gallery. I didn’t include my own political views, which was a struggle. For the first time, I learned to leave politics out and focus on the professional aspect. There were many arguments in the studio – between us and the teachers, and among the teachers themselves.

Gil: We argued over how much it’s possible to talk about politics in an art and architecture studio. This was a particular example which had symbolic aspects. Had the return actually been a real possibility, it would have been too much for the students. The most difficult arguments were between me and the other teacher, about how to see the nakba, the nakba today, the reality of Yafa. It was important to me that we were actually located in Yafa, and the students knew nothing about the city’s history or about the nakba.

Eitan: But it’s a practical plan nevertheless. It’s interesting that an activity by professionals who put aside their political views can contribute something to Israelis who are thinking about the issue, planning the practical aspects of return.

Gil: Even though it could be problematic. Were I a student asked to design a house in the settlements…

Esti Tze’al: The automatic tendency is to be professional, not to think politically, which is burdensome, forces us to confront difficult questions, what’s our place in all this? What if you were asked to build in Ariel?

Ma’ayan: I’d do the same thing, be professional, without getting into the politics.

Lena Kodria’s project: I was inspired by the photos of the building which, although it had undergone conservation, wasn’t in good condition. I dug a pit on the first floor, eliminated the storeroom from the ground floor, turned the second floor into the living quarters, and the gallery is a glass cube facing the plaza that can be entered only from outside. The floor is glass, together with ceramic elements from the building; the pit is visible and can be felt through the floor. My idea was to create a sense of alienation, a feeling of walking over a pit on whose walls pictures are projected. The family no longer has a living room; instead, visitors look into a pit 15 meters deep. The cellar was originally used to store the oranges, for the servants and as a stable. I make it deeper and project images on its walls.

Gil: I still don’t understand what’s going on here – the visitors are over the pit. That’s uncomfortable both for them and for the family.

Lena: I tried to connect to the return, to the discomfort of finding yourself in a Jewish state. The glass symbolizes disconnection. They also have no way of returning to the source, to their lives prior to 1948. That’s what hasn’t been resolved for them. There’s a dialogue here with Micha Ullman’s work about the holocaust, “The Empty Library.” The cracked floor tiles are visible in the pit.

Ofra: Is the exhibit on the internet? Is there a website?

Gil: There isn’t a website. There’s a virtual catalogue.

Eitan: Are there Arab students in the studio? It occurs to me that you’re planning for them, without talking to them. Did you discuss this?

[Everyone answers]: We created it all ourselves.

Gil: Most of the work in design schools is virtual. Nothing is hands-on; students only prepare a prospectus.

Eitan: There’s a political aspect involved – we, the Israelis, who are the beneficiaries of the occupation, are also planning the return.

Someone from the audience: You’re not letting the client be a client. The question is whether he or she wants to be a client, whether he or she is able to be a client, and if that’s unclear then we’re doing the planning because we want it to happen. That’s just great.

Gil: The choice is between doing nothing and doing something. The people who are in contact with him wouldn’t give me his phone number.

Someone from the audience: All of us live with this conflict, and travel on Saturdays with Zochrot because those trips are important to us. I have no interest in planning for the return of an Israeli who’s lived in New York for thirty years.

Esti Tze’al: This terminology, in a democratic country, is shocking, that we even have to think this way about things (the teacher who didn’t want to come, etc.). It was even harder to do something like this today.

Gil: After all the difficulties I went through, I don’t know whether I’d do it again. I also don’t know whether I’ll continue teaching there. Someone there warned me about this evening’s event. The students have power, because they pay tuition. Let Zochrot know whether you want your names to appear in the protocol of the discussion. I’m already in trouble, since I’m a teacher at the school.

Esti Tze’al: On the way here, a list of journalists appeared, declaring they’ll stand united. Too bad they didn’t think of it earlier.

Gil: But who’ll support teachers who use Zochrot’s material? There was a case just recently of a teacher reported for teaching about the nakba.

Someone from the audience: I respect what you did – you participated, chose various ways to express your ideas, nobody forced you, you found your own way, but when you talked about the topic from a professional perspective and said you refrained from becoming involved personally or morally, I panicked. Let me tell you that you have another year or two to talk that way, but when you begin working in the field you’ll have to begin making decisions and you won’t be able to continue hiding behind the excuse, “I was only a student.” What you did belongs to you, and it doesn’t matter how you justify it. I recall with sorrow work I designed. Professionals employed by others can’t choose the projects they work on. I was given a neighborhood in Ariel to work on; luckily, I got sick and left. I refused to work on a project for a settlement, and was fired as a result. You can design for someone, whomever, Arab or Jew, or you can design something because it’s the right thing to do. Your design makes a political statement. You could have restored the house, or created a “little house on the prairie.” Every choice is a political act. Your professional judgment involves politics, because politics is power.

Gil: They learned that the hard way, because the school refused to exhibit their work. A right-wing student refused to participate, to touch the past, because as far as she was concerned Arab architecture is aggressive and invasive. She designed a private space for a childless yuppie couple, forcing herself to carry out the assignment. האם זו הכוונה? She designed a public bathhouse that she stuck on the building, serving people from all religions, very cute דוקי? , since everyone is nude and you can’t identify anyone’s ethnicity אני מבין כי זה חמאם לנשים.... . She created for herself the assignment she wanted – the bathhouse was to serve diplomatic staff. She also complained about the project, and she had a right to say it was hard for her. We even considered changing the assignment, but didn’t. The student who’d refused actually wanted to come speak this evening, but she was unable to do so for personal reasons. It was hard for me to hear her views.

Ofra Lit Yeshua: Many people avoid seeing things in human, moral terms, and focus instead on the professional aspects of their work (like lawyers, for example). I believe professionals truly want to think that way. They also talk like that in the military.

Gil: There’s no answer to that question. Everyone makes their own decisions. Two students wrote a letter to the administration, which led to a serious discussion. It wasn’t concealed. One student, who’s still a student of mine, had great difficulty carrying out the project. I bear her no grudge.

Umar: I imagine that during the project people expressed fear about the return of refugees and other things. Did people avoid tough questions about the return, see it as other than something humane, private, symbolic? Are you interested in what the refugees themselves think? Did you ask them? What do you imagine the owner of the house would say?

Lena: We couldn’t ask the client; we had to imagine him. I used my own personal feelings – how would I feel if I returned? I felt very uncomfortable, alien, as he would.

A question from the audience: What do you think about the return?

Answer: That’s political, and we don’t want to discuss it.

The audience: We also live with the idea, and have no answer.

Esti: How did you change over the course of the project, from before it began until now?

Answer: I didn’t change. The project was about a person coming from a different culture, so I designed the house to make him comfortable.

Umar: What you thought would make him comfortable.

Esti: Did the information you were given make you think about anything you didn’t know?

Audience: What did you think about the client?

Lena: I didn’t view him as an Arab coming for revenge, but as someone coming to live in a house.

Ma’ayan: I looked at it historically, that there would be a gallery presenting the history.

Umar: Did the project make you aware of other Palestinian houses located near where you live?

Ma’ayan: No one takes care of such buildings. Either they’re demolished or disappear behind other structures. I live in a moshav located on the ruins of an Arab village. I didn’t know that before this project; I found out during the project, because of it.

Esti: There’s an internet site called “The Jaffa Project.” It’s amazing to see photographs of Manshiyya, the lives that are no more, the neighborhoods and buildings which we know, in which we live, that have their own other history.

Eitan: Lets get back to Zochrot. What we’re doing here is to learn about planning the return of Palestinian refugees, including to Tel Aviv – Jaffa. We have a group of volunteers, and it’s interesting to meet students who, in a sense, had the return imposed on them, and had to deal with it professionally. I see that as another possibility, not from the ideological point of view like Zochrot’s. Gil, your courage is very impressive in the face of much opposition. That’s an example of how radical activity is possible despite serious opposition. Perhaps even forcing people to do things. We can discuss the moral issues, and criticize what you did, but what’s important is that the students created something and showed it to the world. That’s an important contribution to the discourse about the return, to our lives here.

Gil: There were hundreds of visitors. I talked to someone who didn’t understand what was going on. The discussions with visitors didn’t really focus on the students.

Esti: What did your parents’ think?

Ma’ayan: My mother works in a bank. She thought about wealthy clients of the bank who might contribute for renovating the school.

Ofra: You assumed that these people would return to the society as it currently exists, a society that is overwhelmingly Jewish.

Gil: That was the natural assumption. A family returns from abroad and obviously finds what exists.

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

Bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse

bibishouse