Cultural genocide extends beyond attacks upon the physical and/or biological elements of a group and seeks to eliminate its wider institutions... Elements of cultural genocide are manifested when artistic, literary, and cultural activities are restricted or outlawed and when national treasures, libraries, archives, museums, artifacts, and art galleries are destroyed or confiscated.

– David Neressian.1

For approximately the past hundred years, the Zionist movement has been engaged in an intense process of nation building in the land of historic Palestine. The problem, from the Zionist perspective, was the existence of a predominantly non-Jewish Palestinian population in the very area slated to become a Jewish state. The solution, from the Zionist perspective, was the disappearance of the Palestinian people.

For more than sixty years, the attempt to disappear Palestine has taken three primary forms: the physical destruction of Palestinian property and expulsion of people from their homes, the legally enshrined discrimination against Palestinian people both inside and outside Palestine, and the ongoing process of cultural genocide that threatens Palestinian identity at its core. These processes are inherently intertwined, but the first two are often given more attention than the last. This study will briefly touch upon physical destruction and legal discrimination to provide a framework for understanding the primary topic of the study: an example of the ongoing process of cultural theft and destruction.

In 1948, much of the wealthy and formally educated Palestinian population was concentrated in Jerusalem and other urban centers. When Zionist militias swept through these neighborhoods, they physically pushed thousands of people from their homes and caused tens of thousands more to flee in fear. Many Palestinians left in haste, grabbing only what they could carry as they ran. Others thought they would return a few weeks later, once the fighting died down. In many cases, members of the educated class left behind some of their most prized possessions: books.

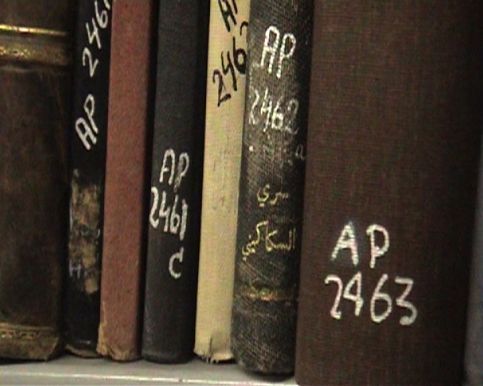

The soldiers raiding these West Jerusalem neighborhoods were closely followed by teams of librarians from the Jewish National and University Library at Hebrew University (later referred to as National Jewish Library or simply the National Library). They gathered approximately 30,000 books from private Palestinian libraries and, according to testimonies from those involved in the project, began to catalog books by subject and often by owners’ names. In the early 1960s, however, close to 6,000 of the books were revisited and labeled with the letters “AP” for “abandoned property”.2 The library catalog shows no information on provenance, or former ownership. If that information had formerly been recorded, it seems to have been erased or at least carefully concealed.

To this day, the books’ call numbers begin with the letters “AP.” The National Library has thus maintained a likely unintentional collection of looted Palestinian books, easily identifiable to those who understand what “AP” means. It remains unclear why certain books were labeled “AP” and others were not. Indeed, the remainder of the 30,000 plundered books, which were embedded into the library’s general catalog and are also still housed there, are much more difficult to identify.

This study will focus solely on the 6,000 books with the “AP” designation, and aims to contribute to uncovering a particular historical episode and to offer suggestions on how to move forward with the information the study gathers. It will place the story of Palestine’s looted books in the larger political contexts of Zionism and other cases of looted cultural property during times of war and occupation, namely that of Jewish property looted by Nazis. Most concretely, it will begin to establish an understanding of how the “Abandoned Property” books at the Jewish National and University Library may be linked to their former owners and eventually restored to their place in Palestinian cultural memory.

Historical Context

“Imagine that you wake up one day and your entire human environment is gone.” Sami Abu Shehadeh, PhD student, political and social activist, and Yaffa resident, attempts to explain the impact of the Nakba on the Palestinian people. Nakba, or catastrophe, is the Arabic name for the displacement and dispossession of the Palestinian people immediately before, during, and after the founding of the State of Israel. On May 13, 1948, one day before Israel declared itself a state, Zionist armies literally pushed 50,000 Palestinians from Yaffa into the sea. Boats transported people to Gaza, Egypt, and Lebanon, where many of them remain today.3 In a strikingly short time span, Yaffa’s Palestinian population dwindled from 120,000 to fewer than 4,000 – an entire human environment disappeared.4

People are often displaced during war; they either flee the fighting or are driven out at gunpoint. When the fighting ends, they begin the sometimes complicated psychological and legal processes of reclaiming their land and property. The case of Palestine stands out as one of the more extreme cases of displacement, one in which the fleeing of the indigenous population was not incidental but was necessary for the creation of a Jewish state in historic Palestine. Because the ethnic cleansing was incomplete, however, the new Israeli state enacted laws and policies to guarantee the creation and continuation of an artificial Jewish majority.

In 1950, the Israeli government passed the famous “Law of Return,” guaranteeing that “Every Jew has a right to come to this country.”5 The law describes the granting of Israeli citizenship to any Jew in the world who wants it. Meanwhile, the right of return for Palestinian refugees, a right guaranteed to all people in the world and specifically reaffirmed for Palestinian people by the UN in the 1948 Resolution 194, has been systematically denied.6 Arabic street names have been replaced with the names of Zionist leaders. Hundreds of Palestinian villages have been destroyed, and the rubble of homes covered by fast-growing non-native pine forests planted by the Jewish National Fund with donations from around the world.7 One of the most striking laws is the Absentee Property Law, which declares that those who left the country during the fighting of 1948 no longer have rights to their property if they first left to an “enemy country,” and that those internally displaced are considered “present absentees,” still without access to their land and property.8 As many who fall into the latter category often bitterly remark, “We’re here when it’s time to pay taxes, but we’re not here when we try to claim our rights.”

In 1948, the Custodian of Absentee Property took control – but not ownership – of all refugees’ property, including books. This measure was supposed to be temporary. In 1950, the Absentee Property Law declared the Custodian the “owner” of the property until a proper owner came forward, and at the same time made it virtually impossible for Palestinians to come forward to claim their property.9

Not only would an acknowledgment of Palestinian ownership threaten Zionist legitimacy, but the incorporation of the books into the Israeli narrative actively served Zionist interests. While the institutions could have simply discarded the books, their preservation has become part of Israel’s conception of itself. Just as hummus is now an Israeli food, Palestinian books are now Israeli artifacts. The colonizer’s identity exists only in relation to the colonized.

At the same time, the “Abandoned Property” books provide a reminder of a past that Israel would prefer to forget. While their owners remain scattered throughout the world in exile, the books sit in Jerusalem, severed from their owners and their former homes but housed with each other, still in historic Palestine.

The AP books also serve as a testament to the burgeoning intellectual culture of Palestine and the Arab world in general, and Jerusalem in particular, in the 1940s. These books are not the average mass-produced popular fiction or cheap commercial publications. They are largely scholarly volumes, mostly in Arabic, and many are rare or out of print today.

The maintenance – whether intentional or not – of the AP collection is thus especially poignant. While the Israeli government and affiliated institutions have attempted to render the AP books meaningless to Palestinian people, their efforts have proven incomplete. Researcher Gish Amit uncovered this story, and projects like The Great Book Robbery – a film and interactive website including translation of part of the National Library’s catalog of AP books – continue its publicity. To my knowledge, neither the National Library nor those attempting to shed light on this case have conducted provenance research regarding these books, so this study aims to begin this process. But first it is useful to explore other examples of looted cultural property – particularly in Nazi Europe – and the process of its return to its former owners.

Nazi Looting of Jewish Cultural Property

One of the best known examples of physical and cultural destruction of a people is the Nazi holocaust perpetrated against Jews and others. I will focus not on physical destruction of people or materials, but on the looting (and survival) of Jewish cultural property, particularly books. No two historical events are the same, but it is instructive to examine some of the parallels and differences between cases of Nazi looting of Jewish property and Zionist looting of Palestinian books.

The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was established in 1940, and over the following years confiscated millions of Jewish cultural items. Though occasionally coming into conflict with Nazis who simply wanted to destroy Jewish cultural property, the ERR had widespread governmental support from those who sought to understand their “enemies”.10 The ERR kept detailed records of the confiscation of libraries, with addresses, dates of seizure, and the number of crates shipped from each place. Some of these ERR lists survive to this day.11 It is unclear whether such detailed official documentation exists in the case of Palestine, but thus far only a small amount has been discovered.

Eventually, in both the cases of Palestine and Nazi-controlled Europe, most victims had fled or were forcibly removed, and the books remained under the control of the occupying power. As in Palestine with the Custodian of Absentee Property, “[t] he property of Jews who had fled the Nazi onslaught was declared ‘ownerless,’ and therefore the ERR had the ‘obligation’ to store it in safe places within the Reich”.12

Because the Nazi government sought to understand the Jews, it often forced Jewish laborers to process and catalog the books. The conscripted staff of the Reich Security Main Office, or RSHA, found itself in a precarious position. On the one hand, Jewish librarians wanted to document and care for these stolen Jewish collections; on the other hand, they worked in inhumane conditions for a government that wanted to annihilate them. Additionally, the threat of deportation to death camps hung over everyone, and eventually most of the workers were indeed deported.13

Similarly, Palestinian prisoners of war in 1948 were forced to loot each other’s homes, and in some cases their own, to gather books from them and prepare them for removal by the National Library.14 Since the cataloging took place only after the war ended, the labor was no longer forced prison labor, but Palestinians were still needed for their Arabic language skills. Aziz Shehadeh, a Palestinian lawyer with Israeli citizenship, loved his job cataloging books in the National Library, but also notes that, “I’ve seen the entire Palestinian tragedy through these books. A catastrophe.”15

Multiple efforts at restitution of looted Jewish property have been conducted. These fall roughly into two categories: those conducted just after the end of World War II and those currently under way as a result of renewed efforts to retrieve stolen property. A few of the more instructive examples can be used as a basis for understanding and beginning to work on the case of looted Palestinian books and other property.

In 1941, the Nazis established Theresienstadt concentration camp in a town called Terezin on the outskirts of Prague. This camp housed wealthy and prominent Jews from various countries and served as a “model camp” to show the world that the Nazis’ treatment of Jews was humane. Therefore, those in the camp were, at least at the beginning, permitted many of the amenities not usually provided to concentration camp inhabitants.16 One such amenity was a community library and bookmobile.

Many people arriving in Theresienstadt brought books with them, and thus a collection was established. Nazi authorities soon supplemented this collection with libraries stolen from Jewish institutions throughout Europe. The books had no common language or subject, and were cataloged by professionals in the library. Eventually, the Nazis’ motivation for the operations in the library became much more insidious: Jews were to catalog materials for future inclusion in the “Museum of the Extinct Race.”17

Eventually, the vast majority of Theresienstadt residents were deported and killed. The head librarian and one other staff member survived, and voluntarily remained in the camp for three months after liberation until they could fully organize and catalog the 100,000 volumes in the library. The books then found their new home in the Jewish Museum in Prague.18

In the years immediately following World War II, the Jewish Museum in Prague underwent a massive process of restoring materials to their prior owners. Of more than 190,000 volumes that the museum acquired during and immediately after the war, 158,000 were returned.19 In 2000, the Czech Republic passed a restitution act that required all state institutions to return art obtained illegally between 1938 and 1945. Although not a state institution, the Jewish Museum committed itself to the spirit of the act and began provenance research on many of the items in its collection. Additionally, the museum has a section on its website called “Terms for the filing of claims for the restitution of books from the library collection of the Jewish Museum in Prague which were unlawfully seized from natural persons during the period of Nazi occupation.” Explaining that all books “shall be transferred free of charge to the natural person who owned them prior to the seizure,”20 the website lists specific instructions on how to file claims, which descendants and relatives may do so, and the documents required.

Austria and Germany, perhaps because of their unique culpability in regards to the Nazi Holocaust, have conducted rigorous provenance research and returned more items than have most other countries. In Germany, the Lost Art Internet Database contains data on cultural objects which as a result of Nazi persecution or the direct consequences of the Second World War were removed and relocated, stored or seized from their owners, particularly Jews, or on cultural objects where, because of gaps in their provenance, such a story of loss cannot be ruled out as a possibility.21

The database is divided into two sections. The first, “Search Requests,” allows those who have lost items to register them, and allows current owners or custodians of questionable objects to search for claims to those objects. The second section, “Found- Object Reports,” does the opposite: it allows current owners to register items with questionable history and individuals and institutions to search for their items. Clicking on an individual record brings information about the item as well as a photograph of the object. Although the majority of the material in this database is art, this can again be a useful model for thinking about the restitution of other cultural property, including books.

In 1998, Austria passed the Art Restitution Act, and in 2009 modified federal laws concerning the restitution of cultural property. The Commission for Provenance Research has since worked with federal museums and collections to inspect materials and archives for signs of previous ownership. This is not primarily a response to individual requests, but is an ongoing effort deemed important in and of itself (Commission for Provenance Research, n.d.).22 In its introduction to its Provenance Research and Restitution project, The Austrian National Library recognizes its history and accepts responsibility for its role in the plundering of Jewish property. After declaring that the institution’s “historical heritage… is not free of injustice and guilt,”23 (Austrian National Library, 2007, para. 1) it poignantly affirms that “[o]nly by an exemplary, sensitive, and honest dealing with its own past can the Austrian National Library lay claim to credibility as the central memory institution of this country”.24

In contrast, the case of looted books in Belarus is perhaps more similar to the current state of AP books. The National Library of Belarus received more than one million books at the end of the war, half of which had been looted from Belarus, the other half from France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. While little attempt was made to identify books during the Soviet regime, the years since have seen provenance research efforts for at least a small portion. Several thousand books with identifying marks have been transferred to the Rare Book Department, which has created catalog cards and other data files on the books, now online.25

Despite these small efforts, many limitations remain. First, a number of the Hebrew and Yiddish language books have yet to be cataloged. Second, only a small number of the trophy books have been transferred to the Rare Book Department, with the vast majority of them still somewhere in the library’s general holdings and virtually impossible to identify. Finally, while some provenance research is being conducted, there is currently no effort or willingness to return the books to their owners, with the exception of a small number of books returned to the Netherlands .26

Similarly, the “Abandoned Property” books in Palestine remain under the control of a government unwilling to return them to their owners. Unlike in Minsk, where the National Library of Belarus has acknowledged the existence of the books and the fact that they were looted, the National Library in Jerusalem has yet to do so. While the case of Palestinian stolen books is made somewhat easier by the designation of “AP” by Israeli authorities, we must remember the tens of thousands of books that did not receive this designation and are probably embedded in the general collection, similar to the books in Minsk. Community representatives as well as individual countries have worked to identify and occasionally return looted items. In late 1951, Dr. Nahum Goldmann of the Jewish Agency and World Jewish Congress called a meeting in New York of twenty-three Jewish organizations to discuss material claims. The result was the formation of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, or the Claims Conference. The Conference represented those organizations present and began to negotiate with the German government for compensation and restitution of looted materials. Negotiations resulted in agreements, which the Claims Conference notes on its website were “unique in human history. All three entities involved—the Claims Conference, West Germany, and Israel—had not existed at the time of World War II, and yet all entered into an agreement for compensation for crimes committed during that time”.?

To date, as a result of laws negotiated with the Claims Conference, the German government has paid more than $60 billion to Nazi victims, and the Conference continues to work with governments and banks to more completely compensate victims for their losses.28 The organization’s extensive website includes detailed information about every aspect of its work, including a large section on Artwork and Cultural Property, and we would be well served to look at the Conference as a model for the case of Palestine and restitution of property, both cultural and otherwise.

In 2001, the Commission for Looted Art in Europe created the Central Registry of Information on Looted Cultural Property 1933-1945. Operating under the auspices of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Judaic Studies, the Central Registry researches, documents, and publishes information on the looting of cultural property by the Nazis, and advises families and institutions. Perhaps most impressive is the “Information by Country” section of its website, which lists more than forty countries and organizes information into a number of very useful categories .29

Considering the examples above, one might ask how specifically provenance research can be conducted when individual owners cannot be found. A valuable case in point is the Offenbach Archival Depot.

Early in 1945, Allied troops uncovered hundreds of hidden repositories containing property stolen by the Nazis. The Office of Military Government for Germany, U.S. Zone (OMGUS), along with other U.S. institutions, took on the responsibility of recovery and restitution. In 1946, when it became clear that this was a bigger job than originally imagined, the Offenbach Archival Depot was established, and by the time it closed in 1949, the depot had returned more than 2.8 million books, in thirty-five languages, to fourteen different countries.30 This effort, the “largest book restitution program in history,”31 was accomplished through cooperation between numerous qualified individuals and organizations, including the U.S. Army, the Library of Congress, its Mission in Germany, and a number of Jewish organizations.32

Offenbach Archival Depot director Seymour Pomrenze, and his successor Isaac Bencowitz, developed a comprehensive system for sorting and identifying the volumes in the facility. Looking at bookplates, stamps, and other markings, staff created an inventory of clearly identifiable items and quickly returned them to their countries of origin. The unidentified items were further researched and again, once enough information was known, returned to their countries of origin.33 In addition, former owners of books could file claims that were examined at the depot.34

This seemingly well-oiled machine was not without challenges. The restitution program was not only the largest of its kind in history, but certain accepted practices did not necessarily make sense here. For example, the return of books to the country of origin in which the Jewish community was recently decimated was not only illogical; it was downright offensive to some. Discussions ensued: while it was commonly accepted that books should be returned to individuals and their families whenever possible, what was to be done with books that were partially or wholly unidentifiable?

Many agreed that the books should go somewhere where they could be of greatest use to the Jewish community from which they came, but with the survivors of Jewish communities now scattered around the world, this was not an easy task. People stressed that regardless of the solution, all distribution of materials should happen in concert with a representative group of Jewish religious and intellectual leaders. Finally, an agreement was reached to turn over the unidentifiable books – about 500,000 items – to the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Foundation (JCR) on a custodial basis, with the stipulation that owners would be sought and their books returned to them. The JCR then began the process of distributing the books to libraries and Jewish cultural centers throughout the world.

When considering European efforts to restore property to Jews, one cannot help but imagine the possibilities that exist in the case of Palestine. A major limitation in the latter case is that unlike the situation in post-war Germany, Israel still controls the documents in question and the lands from which they came, and its officials still refuse to acknowledge the historical fact of Palestinian presence and ownership of property before 1948.

While Israeli law and policy have yet to come close to that of post-war Europe, we can look at international law for guidance. Indeed much of international law was developed as a direct result of the Nazi Holocaust, to try to ensure that nothing of the sort ever happens again. In 1954, the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the event of Armed Conflict declared that “the preservation of the cultural heritage is of great importance for all peoples of the world and... should receive international protection”.35 The Convention prohibits the looting of cultural property and, in the event that this provision is not followed, calls on countries “to return, at the close of hostilities, to the competent authorities of the territory previously occupied, cultural property which is in its territory.”36

One obvious problem in the case of Palestine is that we have yet to see the “close of hostilities.” The system of occupation and colonization is ongoing, and Israel’s borders, which have never officially been declared, are constantly expanding. Still, the National Library in Jerusalem is an institution claimed by a state that is considered part of the international community. We are not merely talking about records of military occupation authorities in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, but documents in an official state institution stolen from people who, more than sixty years later, continue to struggle for their rights of return, restitution, and compensation.

A 1952 letter from Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to the Claims Conference’s first president, Dr. Nahum Goldmann, asserted that “[f]or the first time in the history of the Jewish people, oppressed and plundered for hundreds of years… the oppressor and plunderer has had to hand back some of the spoil and pay collective compensation for part of the material losses.”37 The irony of this statement, when juxtaposed with the case of Palestinian oppression and plunder, cannot escape us.

There is a small minority of Jewish Israelis who, through grassroots organizations like Zochrot (“Remembering”) attempt to decolonize their own identities by remembering the Nakba and supporting the Palestinian right of return. The vast majority of Israelis, however, and all state institutions, still deny Palestinian claims to land and history, because as in many other colonial settler situations, the very acknowledgment of Palestinian identity would necessarily delegitimize Israeli identity. This core contradiction must be faced and dealt with if we are to move forward with any semblance of justice for the Palestinian people. In the meantime, we can begin to prepare for the political moment in which return of property is possible.

While the rest of this study primarily begins the process of individual provenance research, perhaps the most relevant parallel between the cases of post-WWII Jews and post-Nakba Palestinians is the discussion of collective return to a community dispersed throughout the globe. To this end, any efforts at individual linkage of books to their owners should be seen in the larger context of the Palestinian right, as a collective, to control its cultural property.

Searching for Palestinian Owners

The story of Palestine’s “Abandoned Property” books now housed in the National Jewish Library fits squarely into a larger narrative of cultural property theft and destruction in Palestine, as well as that of a long history of similar incidents arising from wartime plunder. In order to add depth and concrete possibility to the discussion of the AP books, this study not only compares Palestine with other historical situations but also examines particular books at Israel’s National Library and identifies ways that the AP books can be linked to their original Palestinian owners.

In a visit to the library, researcher Gish Amit and filmmaker Benny Brunner discovered clear personal inscriptions of Nasser Eddin Nashashibi at the front of a book called Makramiyat.38 In another poignant example, Dumya and Hala Sakakini, daughters of the famous educator Khalil Sakakini, went to the library after hearing rumors that their father’s collection was housed there. The librarian explained to them that the books are abandoned property and they have no right to them, but they were able to look at one of the books they remembered, and confirmed by looking at the marginalia that it was indeed their father’s book.39

These two cases led me to believe that I might find identifying information in some AP books. I set out looking for markings such as name plates and bookseller stamps; handwritten notes, including owners’ names, dedications, and marginalia; librarians’ or catalogers’ markings; and request slips or check-out cards indicating prior use.

There are close to 6,000 books labeled “Abandoned Property” in the National Library, most of which are in Arabic. The website of The Great Book Robbery has translated into English brief records of the first 200 listed in the library’s online catalog. I looked at thirty-four books, most of which appear at the beginning of the list. They seem to be representative titles, encompassing linguistics, science, religion, philosophy, literature, and more. Two of the books were chosen because Amit40 indicated that they may contain identifying information.

While the AP books are in closed stacks, they can be requested and viewed in a reading room. Kara Francis, an Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies graduate student at Hebrew University, visited the library on three occasions in order to view all of the requested books. She photographed any markings that might be useful and sent the data to me. Colleagues fluent in Arabic helped translate notes, decipher handwriting,

and provide further context for some of the names and types of comments found in the books.

Of course, it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a name was written by an owner, a reader, or a cataloger, and many notes were either cut off or faded. I have consulted with others and cross-referenced Amit’s work, but the results are not without some degree of conjecture. I have noted below where assumptions were made. Because this study is more qualitative than quantitative in nature and included only a very small number of books in its study sample, its purpose was more to begin to establish the viability of further provenance research than to generalize about the collection as a whole.

Of the thirty-four books examined, only one had a personal stamp (see Image 1), and three or four had stamps or seals from institutions like libraries or booksellers. One book (AP 77), an astronomy dictionary, had a stamp reading (in Arabic): “Al Taher Brothers Bookstore, Yaffa” (see Image 2). Al Taher Brothers was a known bookseller before the 1948 Nakba.41

Another had a stamp reading “Public Library of Beirut” (or “Public Bookstore of Beirut,” as the words for “bookstore” and “library” are the same in Arabic). Another book (AP 163) bore the seal of a bookbinder named Hijab, located “behind Al Azhar mosque in Cairo” (see Image 3). Interestingly, the book was printed in Istanbul andnot in Egypt.

Unlike stamps and seals, handwritten names were abundant. Again, it was sometimes difficult to tell whether a name was written by an owner, an author, a bookseller, a reader, or a librarian’s note. In some cases an owner’s name was familiar, but in order to make educated guesses about the others, I looked primarily at the placement of the name.

If it was inside the cover or on the title page, it was likelier to be an owner than a reader. If it was a signature repeated over and over again on a page in the margins of the middle of the book, I assumed that it was likelier to be a reader than an owner. If the name was written in what appeared to be librarians’ or catalogers’ pencil, and particularly if it was written next to an AP number, I assumed that this was an author’s name written by a cataloger. This was usually verifiable with a quick look at the catalog, but some books had several authors, making the process slightly more difficult.

Of the thirty-four books, seven to eleven (about 25 percent) have owners’ names written inside them. Four of these are owned by the same person, Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib, whose name was mentioned by cataloger Butrus Abu-Manneh in an article by Gish Amit:

Every book had a sequential number… and beneath it we wrote an abbreviation of the owner’s name in English. For example, the letters SAK stood for Sakakini, NIMR meant Nimer, and so on. Those letters appeared both on the inside cover and on the index card.42

This gives further confirmation that “Nimer” was an owner of many of the looted books. Further research shows that Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib was a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood and Arab National Committee in Haifa in the 1940s who survived a 1948 assassination attempt by the Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary organization that later became the Israeli army.43 In addition, an internet search in Arabic brings up a number of forums that list Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib as son of Abdel Fattah, the same name as in the stamp from father to son in one of the books mentioned above (see Image 1). It can thus reasonably be assumed that the leader and the owner are the same Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib. In addition, I confirmed with Gish Amit that not all of the AP books were taken from the Jerusalem area; many books from Haifa and other parts of Palestine also ended up at the National Library.

In two books, we found the name of Sakakini, one of the other owners mentioned by cataloger Butrus Abu-Manneh. In one, an Arabic drama book, “Khalil Sakakini” was written; in the other, a four-volume work on Turkish civil law, “Sari Sakakini” was written (see Image 4). Khalil Sakakini was a pioneer in the Palestinian educational system of the early 1900s, and Sari was his eldest son.44

We had specifically sought out one of these books because of its mention in Amit’s article, whereas the other we came upon in our search of some of the first books listed in the catalog. Interestingly, in another book that Ait suggested included Sakakini’s name, we found only the name of Dr. Yusuf Haikel, the last mayor of Yaffa before 1948 who later served as Ambassador of Jordan in Washington and many other cities around the world.45 Three or four of the thirty-four books contained apparent personal dedications. In an Arabic language book (AP 23) was written, “Gift from Isaf Nashashibi to Saleh Nammari,” the latter name having been crossed out (see Image 5). Another book (AP 22), one of Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib’s religious books and one with the most writing, included several names, dedications of prayer to keep the book safe, and a handwritten dedication from father to son (see Image 6).

In some ways, marginalia can provide the richest data, as there can be many types of notes written in margins by a variety of people. On the other hand, this information is also hardest to link to a specific prior owner without much more research. Indeed, we did find marginalia in many of the books, but it was often unclear who wrote the notes, and most of the notes were obviously about the text itself and did not clearly indicate ownership.

Of the thirty-four, we found sixteen with marginalia. This category excludes notes that we can reasonably assume were written by librarians and catalogers; these will be addressed below.

In a few cases, the opening pages of a book had a handwritten table of contents and/or what appeared to be a list of several volumes or books in purple ink, presumably by an owner. In some cases, we found what appeared to be prices, and in others, dates (sometimes date of publication, sometimes not) inscribed in the first pages. Oftentimes we found notes on the text, including definitions of words, translations of Arabic words into Hebrew probably by Israeli researchers (see Image 7), and grammatical notes (see Image 8). Occasionally a line of poetry was written (see Image 10), or a comment on the prestige of a particular writer. Other notes and/or drawings appeared to be simple doodles (see Image 9).

It is clear that a variety of people, from the original owners to present day researchers and everyone in between, have interacted with these materials, and that these books have a rich story to tell. Telling this story is beyond the scope of this particular study, and the precise context of all of the notes and guesses about who wrote them will be left for future research.

As far as catalogers’ and librarians’ notes, almost every book had an AP number and/or author’s name written on the inside cover or title page. Since these gave us no more information than we already had from the catalog, I excluded these. However, I did note the cases in which a call number was included in writing, but was not included in the National Library’s online catalog.

These call numbers could mean that the books had previously been cataloged, or could simply indicate another way of categorizing them now; either way, they can provide more information.

I had occasional difficulty determining whether a note was written by a cataloger or by an owner or researcher. However, we can reasonably assume that most written in the same pencil as, and in close proximity to, the AP numbers were probably written by catalogers. Furthermore, in some cases we found what Butrus Abu-Manneh referred to as cited above: the letters “NIMR” to signify Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib’s books (see Image 11).

Twelve to fifteen of the thirty- four books had what appeared to be catalogers’ or librarians’ notes other than the simple AP number and author’s name. In most cases, these notes were numbers: call numbers, dates, and other unidentified numbers. Some notes were harder to decipher than others, and as with the marginalia, the exact codes used by librarians and catalogers must be further researched if we are to glean definitive information from their notes.

Eighteen of the thirty-four books had request slips or check-out cards. This does not necessarily mean that the rest of them have never been viewed; in fact, it is likely a fluke that the request slips are still present, either accidentally or purposefully left by a researcher. I noted the slips and cards because they tell us more about the story of the books themselves. For example, many of the check-out cards contained stamped due dates, indicating that the books were once available for check-out, whereas they are now in closed stacks. Most of those with check-out cards

had stamped due dates in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. One had a stamped due date of 2008, which either means the AP books were able to be checked out until very recently, or that this book was only recently classified as “Abandoned Property.” In addition to physically examining the books themselves, I looked at the National Library’s online catalog for further information about the books’ histories. Sixteen of the thirty-four books had notes in their records of “old classification” followed by Dewey Decimal numbers and sometimes subject headings. Most of the rest had at least one Dewey Decimal number in their MARC records, but “old classification” tells us that the books may have been previously cataloged before being designated “Abandoned Property.” This matter calls for further research.

Notably, though not surprisingly, the National Library contains no indication of former ownership in its online catalog. Including information about provenance in catalog records is not uncommon, particularly in rare book collections. In fact, in the past few decades, several MARC record fields have been added, and official cataloging rules and practices have been adopted to facilitate the documentation of books’ histories.47

For example, in the wake of World War II and the closing of the Offenbach Archival Depot, The Library of Congress (LOC) received more than 5,700 items from the JCR. The books were given bookplates to honor their history, and the LOC entered a provenance note in the MARC record of each book.48 MARC tag 561 for the book Afn shprakhfront reads, in part, |a Vols. 1 (1934) and 3/4 (1935) [under P10.A35] of Set 1 of this title were presented to the Library of Congress by Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., a New York-based umbrella organization that served as a trusteeship for the Jewish people in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust.49

This first step of acknowledging looted property can lead to the further step of return.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

When I began my research process, I feared that we would examine dozens of books and find no personally identifying information, or at least none that clearly indicates owners. I was pleasantly surprised that about one quarter of the books we viewed indeed had owners’ names written inside, and many more had additional information that can be used to identify owners. This confirms that return of the materials to individual owners, while tedious, is indeed possible.

The amount and quality of information we found in just thirty-four books is astounding. We know who some of the owners were, which bookstores or publishing houses they came from, who has requested to view these books over the years, what information people found interesting in the books, what words researchers needed to define, and much more.

Still, there is ample room for further research into this case and for further analysis of the research already conducted. Much could come from the examination of a larger percentage of the AP collection, and eventually from a full database of all the books and all the information we can glean from them. However, this would require many hours of library visits and collection and organization of data. Before this step is to be taken, it seems useful to explore more fully the data we already have. For example, without too much difficulty, one could find descendants of those owners whose names are in the books. We could also search for the sixty people or families listed as former owners in the National Library report of March 1949.50 It might also be possible to contact some of the booksellers or families of booksellers and printers listed in the catalog or stamped in the books, and to inquire about the records they kept.

For the less clear markings in the thirty-four books I examined, it would be useful to show photographs to someone more versed in cultural and intellectual history of Palestine in the 1940s as well as National Library cataloging practices. This way, we could begin to tell more definitively by the types of markings, inks used, placement of writing, and other factors, who wrote which notes and what they mean.

During this process, I tried only a couple times to contact the National Library, and only with general questions about the story of the books, because I did not want to jeopardize my ability to conduct the research. It would be useful to interview more people involved in the cataloging process of the AP books between 1948 and today, and perhaps to find sympathetic library workers currently in the system who either know more about the story of the books, or who are interested in finding out more. While some of the research I conducted would have been necessary no matter the degree of cooperation with the institution, the work would have been expedited had we been able to learn more from the library itself.

As we continue to search for former owners, it is equally important to assert that the AP books are indeed Palestinian books. When doing so we can learn much from the example of Jewish books looted by Nazis. In the case of the Offenbach Archival Depot, debate arose about where unidentified books should go. It was never questioned that they should be “returned,” the issue was how to return books to a community dispersed throughout the world.

The similarity to the case of Palestine is uncanny. The worldwide Palestinian population stands at over ten million, with more than half in exile and many more internally displaced.51 It is imperative to begin discussions about returning property to Palestinian communities, but there are no easy answers. Who represents the Palestinians? Should the books go into a Palestinian governmental archive? A cultural institution? A Palestinian organization in or near Jerusalem, or as close to the origin of the books as possible? A new library far from Palestine and thus protected from Israeli occupation? The only clear necessary step in this process is the inclusion of Palestinian voices, and particularly Palestinian refugee voices, in any discussions on the return of their collective property to their community. In some ways, the importance of this story lies simply in its telling, and the AP books as a collection take on new meaning with each examination. Not only do they represent a more or less unintentional reminder of Israel’s theft of Palestinian cultural and intellectual property, but they are also a living archive with meaning in the relationship between and among the books and their owners. For example, while AP book owner Mohammad Nimer Al-Khatib was part of a number of groups specifically aligned with the famous Husseini clan52, Dr. Yusuf Haikel, another AP book owner, “was considered to be an enemy of the traditional supporters of Haj Amin Al-Husseini, and a supporter of King Abdullah.”53 One might wonder how the books’ or the men’s relationship to each other changes within the context of a captive collection of looted books from six decades ago.

The disappearance and theft of Palestinian cultural heritage corresponds with the disappearance and theft of Palestinian land and the largely unsuccessful Zionist attempts to disappear Palestinian people and identity. Many Palestinians talk about the ongoing Nakba that continues through simultaneous processes of occupation, colonization, and apartheid. Laws, policies, systems, structures, and attitudes keep the Palestinians struggling for survival on multiple levels. For example, the censorship of Palestinian textbooks inside Israel is not unrelated to the maintenance of a collection of so-called “abandoned” Palestinian books in Israel’s National Library.

Similarly, the work of Baladna in Haifa or the Yafa Cultural Center in Balata refugee camp to preserve Palestinian identity is not unrelated to the efforts of Gish Amit and Benny Brunner to document the story of the AP books. The struggle of refugees to return to their homes is not unrelated to the struggle to return the AP books to their rightful owners. The abundant research in the case of Nazi looting of Jewish property is not unrelated to the need for research in the case of Israeli looting of Palestinian property.

In July 1948, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion famously wrote in his diary about the Palestinian people, “The old will die and the young will forget.”54 The old may be dying, but the young are not forgetting. Under the surface of any interaction in or about Palestine lie the ghosts of the past, powerfully resurrected in a multitude of cultural heritage projects with one eye on the present and another looking towards the future. It is my hope that this study of the “Abandoned Property” books will contribute to an ongoing process of decolonization through memory and return.55

Acknowledgements

This project could not have been completed without a tremendous amount of help from colleagues and friends. For providing me with background information and for assistance with collecting data, translating, and editing, I thank Gish Amit, Benny Brunner, Kara Francis, Mona Halaby, Ali Issa, Lubna Alzaroo, Noor Ogly, Ryvka Barnard, and Ruth Mermelstein.

Hannah Mermelstein is a Queens college graduate, school librarian and Palestine solidarity activist based in Brooklyn, New York.

Endnotes

1 David Neressian, “Rethinking cultural genocide under international law,” Human Rights Dialogue (Spring 2005): para. 3. Retrieved from http://www.carnegiecouncil. org/resources/publications/dialogue/2_12/ section_1/5139.htmlpara. 3)

2 Gish Amit, “A strange monument: The collecting of Palestinian libraries in West Jerusalem during the 1948 war, and their changing fortunes at the Jewish National and University Library,” 2011. Received from author; to be published in 2011.

3 PalestineRemembered.com, 1999-2006.

4 Sami Abu Shehadeh and Fadi Shbaytah, “Jaffa: From eminence to ethnic cleansing,” Al Majdal 39/40 ((2008/2009): 8-17.

5 David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Shapira, and Yosef Sprinzak, Law of return 5710-1950, (1950). Retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ MFAArchive/1950_1959/Law%20of%20 Return%205710-1950

6 Badil, Refugee & IDP rights (2010). Retrieved from http://badil.org/en/refugee-a-idp-rights

7 Yeela Raanan, “The role of the Jewish National Fund in impeding land rights for the indigenous Bedouin population in the Naqab,” Al Majdal 43 (2010): 34-38.

8 Adalah, Major findings of Adalah’s report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (1998). Retrieved from http://www.adalah.org/eng/intladvocacy/cerd- major-finding-march98.pdf

9 Wakim Wakim, “The exiled: Refugees in their homeland,” Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics & Culture, 9(2) (2002): 52-57.

10 Stanislao Pugliese, “Bloodless torture: The books of the Roman Ghetto under the Nazi occupation,” Libraries & Culture, 34(3) (1999): 241-253.

11 Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, “The road to Minsk for Western ‘trophy’ books: Twice plundered but not yet ‘home from the war,’” Libraries & Culture 39(4) (2004): 351-404.

12 Pugliese, “Bloodless torture,” 244.

13 Dov Schidorsky, “The library of the Reich Security Main Office and its looted Jewish book collections,” Libraries & The Cultural Record 42(1) (2007): 21-47.

14 Mohammad Batrawi, personal communication, January 11, 2011. [Editor’s note: Mr. Batrawi passed away on March 15, 2011, aged 82 years.]

15 Benny Brunner, director, The Great Book Robbery teaser [Motion Picture] (Netherlands: Xela Films, 2010).

16 Miriam Intrator, “‘People were literally starving for any kind of reading’: The Theresienstadt Ghetto Central Library, 1942- 1945,” Library Trends, 55(3): 513-522.

17 Intrator, ‘”People were literally starving...,” 513-522"

18 Intrator, ‘”People were literally starving...,”513-522.

19 Jewish Museum in Prague, “Library Holdings,” in Provenance research and restitution (2004-2008). Retrieved from http:// www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/arestit.htm#3

20 Jewish Museum in Prague, “Terms for the filing of claims for the restitution of books from the library collection of the Jewish Museum in Prague which were unlawfully seized from natural persons during the period of Nazi occupation.” in Provenance research and restitution (2004-2008). Retrieved from http://www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/arestit.htm#6

21 Koordinierungsstelle Magdeburg, Lost Art Internet Database (2011). Retrieved from http://www.lostart.de/Webs/EN/Datenbank/ Index.html

22 Commission for Provenance Research, Commission for Provenance Research (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www/provenienzforschung.gv.at/index. aspx?ID=1&LID=2

23 Austrian National Library, Provenance research and restitution (2007): para. 1. Retrieved from http://www.onb.ac.at/ev/about/ provenance_research.htm

24 Austrian National Library, Provenance research and restitution, para. 7.

25 Grimsted, “The road to Minsk,” 351-404.

26 Grimsted, “The road to Minsk,” 351-404.

27 Claims Conference, About us (2010-2011): para.6. Retrieved from http://www.claimscon. org/index.asp?url=about_us.

28 Claims Conference, Conferences, declarations and resolutions (2010-2011). Retrieved from http://www.claimscon.org/indexasp?url=artworks/conferences

29 Central Registry, Information by country: Overview (2011). Retrieved from http:// lootedart.com/infobycountry

30 Anne Rothfeld, “Returning looted European library collections: An historical analysis of the Offenbach Archival Depot, 1945-1948,” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage, 6(1) (2005): 14-25.

31 Rothfeld, “Returning looted European library collections,” 14.

32 Robert Waite, “Returning Jewish cultural property: The handling of books looted by the Nazis in the American Zone of Occupation,” Libraries & Culture, 37(3) (2002): 213-228.

33 Rothfeld, “Returning looted European library collections,” 14-25.

34 Waite, “Returning Jewish cultural property,”213-228.

35 Yehuda Blum, “On the restitution of Jewish cultural property looted in World War II,” Proceedings of the annual meeting [of the] American Society of International Law, (2000): 91.

36 Blum, “On the restitution…,” 91.

37 Claims Conference, History of the Claims Conference (2010-2011). Retrieved from http://www.claimscon.org/index asp?url=history

38 Benny Brunner, personal communication, February 10, 2011.

39 Haim Hanegbi, The Sakakini House – Katamon (n.d.): 3. Retrieved from http://www/zochrot.org/images/The%20Sakakini%20House%20%E2%80%93%20Katamon.pdf

40 Amit, “A strange monument.”

41 Sami Abu Shehadeh, personal communication, April 24, 2011.

42 Amit, “A strange monument,” 10.

43 Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

44 Amit, “A strange monument.”

45 Amit, “A strange monument.”

46 PASSIA (Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs), Palestinian personalities: A biographic dictionary (2011). Retrieved from http://www.passia.org/ publications/personalities/Sample/H.pdf

47 M. Winslow Lundy, “Provenance evidence in bibliographic records: Demonstrating the value of best practices in special collections cataloging,” Library Resources & Technical Services 52(3) (2008): 164-172.

48 Library of Congress, “Hebraic Section: The Holocaust-Era Judaic Heritage Library,” in African and Middle Eastern Reading Room (2011). Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/rr/ amed/hs/hscoll.html

49 http://lccn.loc.gov/52054681

50 Amit, “A strange monument.”

51 Ingrid Jaradat Gassner, “Palestinians living in the diaspora,” This Week in Palestine (2008). Retrieved from http://imeu.net/news/ article008217.shtml

52 Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem.

53 PASSIA, Palestinian Personalities, 87.

54 Bar Zohar, Ben-Gurion; The armed prophet (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1967): 157.

55 Since the completion of this study, I have personally visited the library and examined more than thirty additional books. The results are similar: an ample amount of marginalia, quite a few owners’ names, and the occasional bookseller stamp. The conclusions are the same: tracing the individual ownership of much of the AP collection is indeed possible, and discussions of collective ownership necessary.

________________________________________

Hannah Mermelstein is a Queens college graduate, school librarian and Palestine solidarity activist based in Brooklyn, New York

Download File