Excerpt from the booklet:

Remembering the Nakba: Tours of Destroyed Palestinian Villages as Pilgrimages of Lament and Hope

by Alain Epp Weaver

From a paper prepared for the Theology and Religious reflection section of the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting, Nov. 20, 2006

Erasing Miska

Let us begin with moments of erasure. In July 2006, bulldozers hired by the Israel Lands Administration approached two structures near an orchard in what is today central Israel and proceeded to destroy them. One doubts that the bulldozer operators knew what the buildings were: the two structures looked old, but they also showed evidence of recent renovation. It didn't take long for the machines to reduce the two buildings to piles of stone. After the rubble had been cleared, other workers came to plant trees: most who would now pass by the site would have no idea that buildings once stood here.

The two demolished buildings in question served, almost six decades ago, as the boys' schoolhouse for Miska, a village in the Tulkarm district of Palestine under the British Mandate. The 1945 census placed Miska's population at 1,060; the 1931 census counted 123 houses. Other village structures included the elementary school for village boys and a mosque. Historians believe that Miska's name comes from the name of the Arab, Miskain, which settled in Palestine's coastal plain during the early years of the Islamic conquest in the seventh century.

Miska was also one of—depending on what one counts as a separate town or village - the between 413 and 531 Palestinian population centers destroyed by the Israeli military in 1948 and 1949. Israeli forces entered Miska on April 20, 1948, expelled remaining the inhabitants, and proceeded to destroy all of the village's buildings, leaving only the schoolhouse's two buildings and the village mosque standing. These new refugees were some of the at least 750,000 Palestinians who became refugees between 1948 and 1950. Shortly after Miska's destruction, Israeli authorities planted trees over much of Miska's land.

For most Israeli Jews, the events of 1948 bear the name, "the War of Independence," and conjure up memories of heroic sacrifice. Palestinians, however, name these events as a Nakba, an Arabic word meaning "catastrophe." Little wonder, for the war of 1948 was indeed catastrophic for Palestinians, tearing apart their society's fabric, dispossessing many of them from their land, and transforming well over half of the Palestinian population into refugees. Some refugees had left their homes to escape from the fighting. Israeli military units forcibly expelled others. For all, the reality after 1948 was the same: they were now the dispossessed, refugees.

A large number of these refugees ended up in United Nations administered camps outside what at the end of the war had become the new State of Israel, beyond the 1949 Armistice Line: many, along with their descendants, continue to live in the refugee camps of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Others, however, remained in the new State of Israel, and so international humanitarian law viewed them not as refugees but as "internally displaced persons." They became citizens of the new State of Israel (albeit not citizens entitled to the same benefits as Jewish citizens).

Like the officially-recognized refugees, these internally displaced Palestinians also lost their homes and properties. As in Miska, Israeli forces leveled the buildings in most of the villages they had depopulated. In 1950, the Israeli Knesset passed the Absentee Property Law, which handed over refugee property to a new state agency, the Custodian of Absentee Property. Much of the this land, in turn, was sold to Keren Kayemeth L'Yisrael, the Jewish National Fund, to hold in perpetuity for the Jewish people. Until recently, the JNF also enjoyed an intimate relationship with the Israel Land Administration (ILA), which also administered state-seized under JNF guidelines limiting property transactions of administered land to Jews only.

Some of the refugees from Miska managed to remain in the State of Israel, with many of them ending up in Tira, one of the main towns in the so-called "Arab Triangle." Geographically they were not terribly far from Miska: it was and is only a matter of a few kilometers. In terms of legally constructed space, however, the distance was great and remains so. Under the Absentee Property Law, Miska's former residents who remained inside Israel received the Kafkaesque Israeli classification, nifkadim nochachim, or, in English, "present absentees": they were "present" in the country, but the law constituted them as "absent" for the purpose of property confiscation.

The destruction of Miska, along with the demolition of hundreds more Palestinian villages, did not take place in a vacuum. It occurred within a specific ideological context. Specifically, it unfolded in the context of a particular (and dominant) Zionist ideology which sought to link spatial and demographic control, which understood the Zionist mandate to be the establishment of a "Jewish" state in which an indispensable part of the "Jewishness" of the state would be demographic control over a circumscribed territory. To understand this ideological context, let us briefly consider the writings and career of Yosef Weitz, who prior to 1948 and beyond served as an official of the JNF. Miska's depopulation and destruction were ordered by Weitz, a long-time advocate of what was (and is) euphemistically called the "transfer" of Arabs outside of eretz yisrael. "Transfer" did not suddenly emerge as an ideology during 1948, but had been widely discussed among Zionists of the left and the right for decades. For Weitz, as we will see, "transfer" was a means to a territorial end, an end framed using the religious language of "redemption" which Zionism had appropriated from scripture and from rabbinic tradition.

During a meeting with the "Transfer Committee" on November 15, 1937, Weitz linked the demographic dimension of transfer with its territorial objective: The "transfer of [Palestinian] Arab population from the area of the Jewish state," he underscored, "does not serve only one aim-to diminish the Arab population. It also serves a second, no less important, aim which is to advocate land presently held and cultivated by the [Palestinian] Arabs and thus to release it for Jewish inhabitants." The Zionist movement simply required more space, and the way to create that space was through the expulsion of the Palestinians.

Remembering Miska Together

Zochrot volunteers joined former residents of Miska in renovating the school buildings, which they in turn used for a variety of cultural events. In mid-June 2006, however, the Israel Lands Administration fenced off the school, and posted its own sign, indicating that the land was private property and entry onto the land constituted trespass. In response, Zochrot joined displaced persons from Miska at the school. Standing outside the fence, they proceeded to drape the fence with 50 meters of white cloth, Christo-style.

Everyone in attendance -Israeli Jew and Palestinian, man and woman, young and old- then had the opportunity to place their own pieces of art on the cloth. To replace the Israel Lands Administration's sign, now covered over, the group hung a new sign reading, "Miska School house-the land belongs to the Miska uprooted people and the entrance is permitted to all with love."

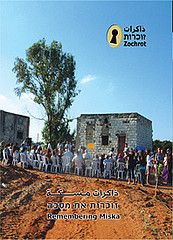

Only a few days later the demolition crews arrived and planted saplings in a renewed bid to bury the village's past. On August 19, 2006, members of Zochrot and Miskawis made a pilgrimage to the site of the destroyed schoolhouse. They looked around for bits of rubble that remained from the demolished building, and used those stones to mark the outlines of the school. They then posted signs with the names of children who had once attended the school.

Download File