Eric Bokobza’s picture asks viewers a simple question: what are we seeing? The facts are clear: a threatening figure points its weapon directly at a woman who’s concealed by a garment and carrying a child in her arms. It’s a picture of a killing, an execution, a murder. But who are these people? Is it a frame from a comic strip, a Japanese manga? Or is the scene allegorical, referring to a reality beyond the picture?

The first version of the painting is located in Holland, in the home of a Jewish collector who commissioned it from Eric Bokobza. The collector, a Holocaust survivor, asked Bokobza to address the iconic photograph displayed in Yad Vashem that shows a Nazi soldier who intends to murder a Jewish women trying with all her might to protect her small son (cf. the photograph in the exhibit, and the video).

The second version of the painting, shown here, was recently exhibited (in May, 2013) in Eric Bokobza’s solo show at the Tel Aviv Artist’s House. The exhibit was accompanied by a catalogue with an essay on the painting by David Shperber who wrote: “Bokobza’s version shows a soldier who isn’t wearing a uniform and has no skin, and recalls previous pictures of executions by artists… this soldier…shoots at an image of the artist portrayed as a child in his mother’s arms. Bokboza has shifted the image of the mother averting her glance that appears in the original version. She’s become a figure who seems to be ‘veiled in black’…The artist places himself in the bosom of the Palestinian mother as a victim of a militarist system.” Professor Yossi Yonah’s article on the painting also suggests these interpretations – identifying the mother as Palestinian while recognizing the picture’s universal character.

I’d like to propose a third reading, a third extra-pictorial sense. I believe this painting exemplifies the total collapse of the system of human law, of natural law. Nowhere on earth would this painting seem to portray something, and be accepted as, “natural” or “normal.” Unlike other portrayals of executions in which the viewer may be able to “take comfort” in the possibility that, despite the terrible violence, those being executed may have been criminals or traitors, if only in the eyes of the executioner, this picture offers no way out. A situation in which a mother tries to protect her infant son from a deadly weapon aimed at her is unacceptable to us under any circumstances.

Identifying the violent figure as a “soldier” expresses the clash between two systems of laws: the one which determines the behavior of the monstrous soldier, on the one hand, and “natural law,” on the other. Bokobza makes us consider the relationship between law and justice. No existing human legal system can justify such a scene. Here is where all human law vanishes and absolute evil appears. A system of laws that permits such an occurrence cannot be human.

I’d like to conclude with a brief reference to Eric Bokobza’s biography as an artist. His unique style of jaunty, colorfully plump caricatures disguises one of the most radical artists working in Israel today. It seems there’s no taboo Bokovza hasn’t addressed in the most avant-garde manner. In 2000 Bokobza was already dealing with representations of homosexuality; in 2006 he examined the place of Jews from Arab lands during Bezalel’s early years, and he recently mounted a particularly challenging exhibit in Kibbutz Bar’am aiming to presence the destroyed village of Bir’im.

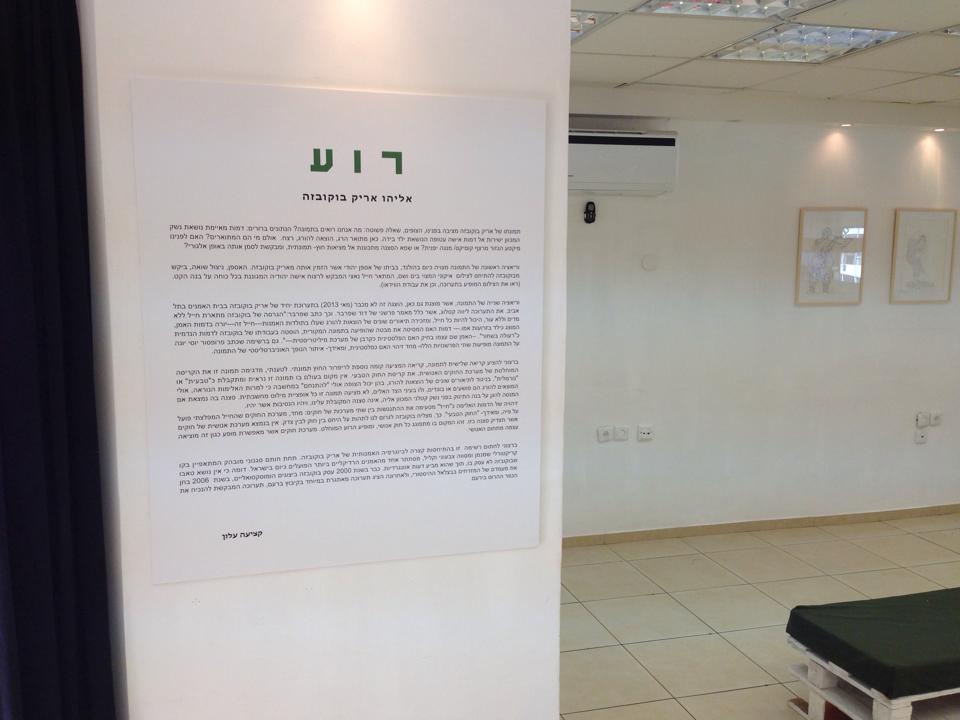

חלל התצוגה רוע / Gallery space Evil

חלל התצוגה רוע / Gallery space Evil

חלל התצוגה רוע / Gallery space Evil