Curator: Eitan Bronstein Aparicio

(Following at this page a text he wrote on the exhibition)

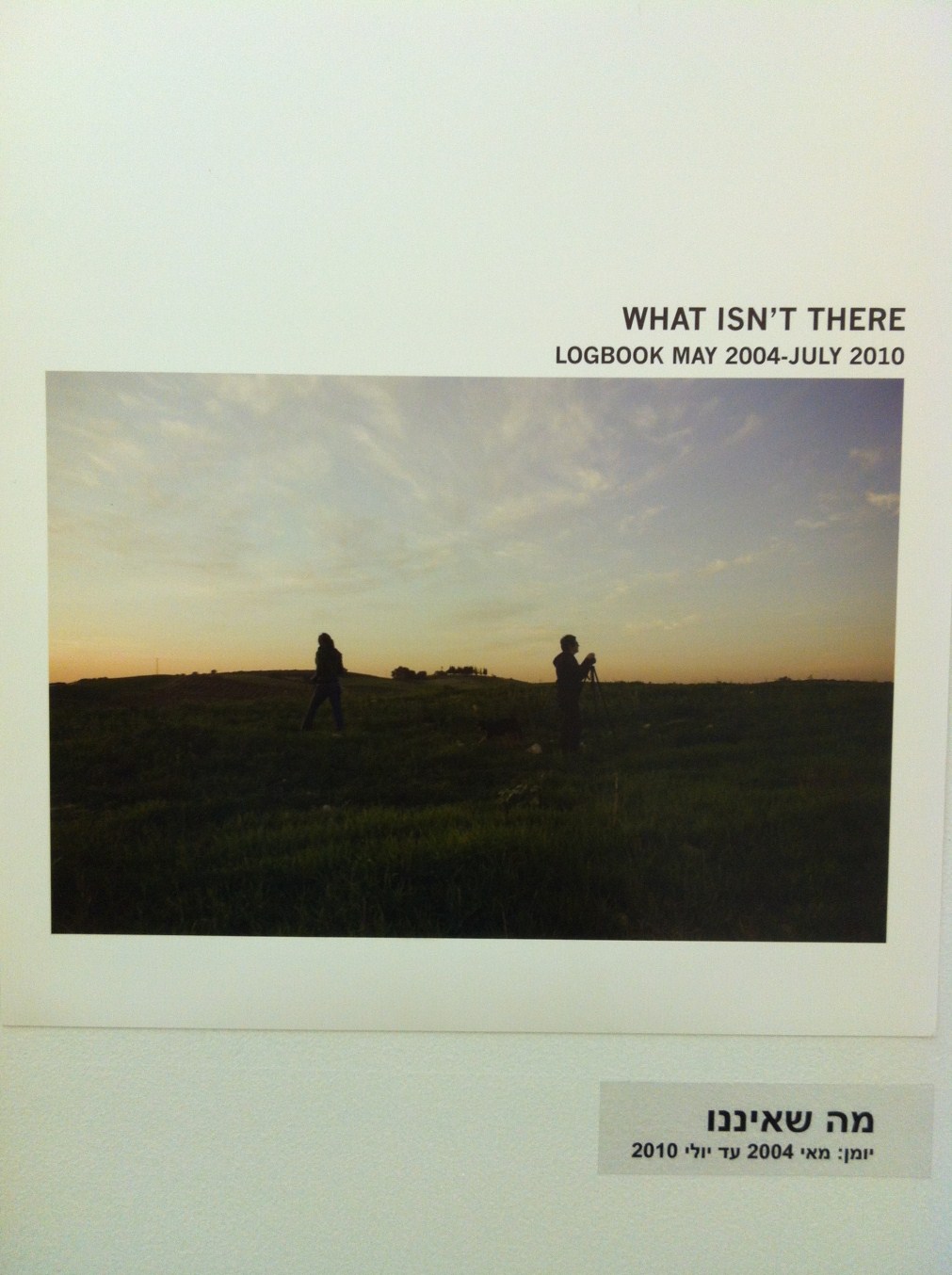

What isn’t there

Villages like dots erased from their letters, these are words from Mahmoud Darwish’s poem Don’t Apologize for What You Have Done. Translated by my friend Fady Joudah, I find myself not only apologizing, but tracing, step by step, that which I didn’t see for over twenty years. I see it as a kind of reparation work, my contribution as an artist to make visible that which isn’t there, that which we erased.

In 1971, my family made Aliyah from Canada. I walked these villages hundreds of times with school trips, with the scouts, picnics with my family. 400 villages that not one of us saw: They were not on our hiking maps, not on our driving maps. I have never seen them still, but I have photographed them.

In 1993, I arrived at my first Palestinian village; it wasn’t there, but my guide, a taxi driver from Nazareth, told me to look harder. Then I saw the crumbling wall and a Sabra in the middle of a pine forest. I began photographing these villages ever since. Today, I work with my partner Tamira Sawatzky, and with each time we return, we continue to build our archive.

What Isn’t There chronicles over 400 villages that no longer exist but for miscellaneous archival materials and remnants that tell us the story of Palestinian lives before the Nakba. In reconstructing a contemporary visual archive of Palestinian villages, What Isn’t There works against the notion of a state archive that excludes aspects of history and memory that doesn’t serve its narrative. The archive functions as a form of remembrance, and in this case, the archive functions as a trace that fragments and destabilizes the dominant narrative of Palestine as recounted by Israeli history, and instead offers what we could call a ‘counter-memory.’

The works here represent some of the photographs I have taken since 1993 that we keep in a logbook. Some of the names have been mis-translated; some of the locations have become confused; these are our notes as we wrote them, unedited, revealing the process of research. In the translation from Arabic to Hebrew to English and with the yawning gaps of time and memory, these mistakes are inevitable. However, with the meticulous endeavors of Zochrot and its brilliant research that will continue to rebuild this missing archive, we have attempted to restore these mistakes to their original names and places. I am indebted to the work Eitan Bronstein and Zochrot for their ongoing commitment to justice and remembrance. I would like to thank Noga Kadman who mapped all the villages for us and for her guided tours, and to Ariella Azoulay who saw our project in Toronto and brought it forward to Zochrot.

Public Studio, July 2012

Elle Flanders and Tamira Sawatzky

What's there

- "Safsaf" (stressed on the last syllable)

- "No, it's Safsaf (stressed on the first)", I replied

- "It's Safsaf", she said emphatically. "You're not from here so you don't know", she said in English.

I thought to myself that she didn't know, because she wasn't from here either. But I knew that in Argentina where I had immigrated from, the first syllable is always stressed. This is also why my Hebrew name Eitan is often mispronounced.

When we got there the excitement was great. She told me a lot about Safsaf from stories told by her family in Lebanon. For her, they are family although they are not related by blood but only by love. They told her about the massacre and rape that had taken place there during the Nakba and about how they wanted to return. Like her, they never actually visited Safsaf because they were born after 1948.

She entered the women's Mikveh (Jewish ritual bath), in the building that used to house the village school. We saw several religious Jews entering and leaving the building.

Then we walked to the open field strewn with stones from demolished houses. It was chilly. We sat on the stones and it started raining. We got wet and loved it.

We then proceeded to Safsufa – the Jewish settlement across the road. There was a public phone at the entrance and I suggested she call her family and tell them were we were and what we had seen.

- "Call Lebanon? How can you do it from here?"

- "Why don't you give it a shot? Maybe you'll make it", I insisted.

She dialed. The call went through and a voice from across the border could be heard in the Jewish settlement located on the lands of the village whose descendants were no on the other end, not too far geographically.

- "Ana fi Safsaf!" she declared in Arabic, laced with a French accent. Huge smiles.

I asked her to give them my warmest regards.

- "How did she respond when you gave her my regards?" I asked later.

- "She didn't".

____________________

When we located her mother's house among the ruins of Qula (near Ramle) it felt just like she would later describe it: out of place and out of time. We were thrilled. It was funny to think that this heap of stones we were sitting on used to be the house of her mother and grandparents. Although we were almost strangers, we embraced. She thanked me for my help in finding the house. I told her I still owed her a lot.

Ever since then, we have been close friends separated by thousands of miles – sharing family experiences and cooperating politically and professionally, planning our joint life together here, in the country we belong.

____________________

Lifta is one of the villages we visited most often. Not because it is one of the most beautiful places in the country, not only because its refugees are still here, and not only because most of its impressive houses are still standing.

In one of our visits, a talented photographer captured her in a profile, sitting on the windowsill looking out onto the enchanting valley. When I later asked her what she thought about in that captured moment, she said, about how the village is empty of the people who want to return.

When we waited for tour participants to arrive in the parking lot facing Maliha, it was the first time I didn't listen to her. She claims she addressed me. Even then, I didn't remember it at all. I didn't listen to her.

No paved road leads westward from Heletz Junction. Only a dirt road leads to where the village of Burayr used to be. I opened the car windows to let some fresh air in, and with it came the village ghosts. I don't really believe in spirits, but if there is one place that made me feel their presence it was Burayr. The village is wiped out. There are almost no house stones left on the ground. A single wall of a large building is still standing. The obviously non-native eucalyptus trees, planted rather dispersedly for post-1948 JNF groves, make the place feel completely alien.

- "Do you feel it too?" I asked her.

She didn't answer now. She was dumbfounded. It took long minutes before she could speak. Later she found the words to better describe her feelings when writing the tour for this ruined village and three others in the area.

Several months later we sat together with twenty others at Zochrot and listened to Amnon Neuman as he told us, or rather refused to tell us about the Nakba massacre at Burayr, which he had taken part in. The painful silence in the room which followed Neuman's reminded me of the thundering silence at Burayr.

____________________

He was born in Isdud. Not too many people know this country as well as he. That is, know it through and through, not just the outer layer we learned about in school, in a curriculum which denied most of its relevant history.

He wasn't just knowledgeable, he was also a kind man and a devoted teacher. A communist in the deepest sense of the word – an activist who distributed the party papers on a bicycle.

One day I picked him up for a tour in the village remains around Ramle, the town to which he had been displaced: Tirat Dandan, al-Haditha, Rantiya, and others. He couldn't stop talking about the history of those places, thousands of years back. He complained that the youngsters were no longer interested in them. I tried to encourage him and he laughed. He always had this typical sly smile with shiny eyes.

During the Zochrot tour to Isdud, he sat under the huge, insect-infested jujube tree near the schoolhouse where he used to learn, which still stands. He told us enthusiastically about his village and then somebody pushed a phone into his hand and told him someone wanted to talk to him. It was his childhood friend, an Isdud refugee currently living in Ramallah. They haven't met in years. Immediately they started chatting like children, cursing and using funny slang terms. He updated his friend from the other side of the Green Line about the neighborhoods and plots that can still be identified. Then we posted a sign next to his school and ate a watermelon which grew in the plot whose name he remembered and I have already forgotten.

When he suddenly died under tragic circumstances I found it hard to accept. His friends gathered in a big hall in Ramle to commemorate him and asked me to say a few words. I couldn't find the strength to go there.

____________________

When we looked for a new office for Zochrot in Tel Aviv, we toyed with the idea that perhaps we would find a location in the houses of Sumayl. I visited the place for the first time. I walked up the stairs near the corner of Arlozorov and Ibn Gabirol streets, and found myself transplanted into another world. Right in the center of the city that never sleeps, it stopped existing and turned into a village. This is also how it's called by its Jewish inhabitants. I walked around a bit, encountering some suspicious looks. Near the parking lot behind Century Tower, I saw an elderly woman hanging the laundry. I approached her, smiled and started talking. She told me that as a young woman she used to live in Jaffa's Manshiya Neighborhood. As a young couple, she and her husband rented an apartment there. When the violence started in early 1948, they left the house in panic and looked for refuge in the city to the north. The Palestinian residents of Sumayl had left by that time, so they found a vacant house. Palestinians used to visit the house and village in the past, but she had no contact with them.

____________________

She came from Canada to visit Palestine for the first time in her life. Her mother came from Wadi Hunayn and her father from 'Innaba. A film crew was documenting her search for traces of her parents in both of these locations and asked me to help her locate them. We drove to Nes Ziona and approached people at the center of town, near the mosque-turned-synagogue. They suggested we ask one of the Zionist founders of Nes Ziona. He was happy to oblige, invited us to his home and showed us some old photos, in which (perhaps) we identified the house where her mother had been born.

From there we drove on to Innaba, next to Annava Interchange named after the ruined village. It was a rather large village and its remains cover a large territory. Here and there we found clear evidence of houses, mainly cactus trees and construction stones. Her father had given her a map drawn from memory, and she tried to use it to locate the lemon tree her family used to grow in the courtyard. We didn't find it. She persisted. Bedouin shepherds couldn't tell us if there was a lemon tree nearby. She wouldn’t give up and the film crew followed her as she searched for the lost tree. Only when night fell and she realized she wouldn't find it, we left. She was very disappointed. At night she stayed with us and was very quiet. By morning she was ill. We drove straight to the hospital where she was admitted.

____________________

We drove to the Jewish settlement of Kerem Ben Zimra to find the ruins of Ras al-Ahmar, some of whose houses were still standing. I was already familiar with her fondness for elderly people, for whom she had respect bordering on awe. But her enthusiasm upon meeting the man who had emigrated from Rumania in 1947 and settled in Ras al-Ahmar took me by surprise. He sensed it and flirted with her. Just as we entered, he asked us if we could help him find a life partner. We were more interested in his history, in the history of the village.

Yes, it used to be called Ras al-Ahmar, until it became Kerem Ben Zimra. He told us there used to be an armed guard to prevent the Palestinian refugees from "coming back to steal what had been theirs" – I am quoting verbatim. From the point of view of the immigrant from Rumania this makes sense, of course. He has to acknowledge the fact that the refugees come from the place he lives in, and that in 1948 their property became his, so he has to prevent them from stealing it back…

____________________

I have never taken my mother to visit the ruined villages shown in these photos. She died two weeks before the opening. Typically, she left me enough time to cry, to wipe out the tears, to cry and wipe the tears again, and then come to my senses to put all the photos in place.

When we finished hanging the photos and titles we decided to go to the demonstration against the new war our leaders are so keen to start. My private grief became mixed with anxiety for the future. She is not from around here, so she finds it hard to accept life in the shadow of such permanent tension. She asked me where the nearest shelter was. What to do if there was a missile alert and she was alone without me. She suggested we take my children and fly to her country for a while. I didn't tell her, but I thought: How can I leave when there is so much destruction left to answer for.

al-Masudiyya

מוזירעה /Muzairia

ולג'ה / Walaga

ראס אל אחמר / Ras al-Ahmar

בית ת'ול / Bayt Thul

בריר / Burayr

דלאתה / Dallata

דיר מֻחיסִן / Dayr Muhaysin

חליקאת / Hulayqat

ח'רבת דאמון / Khirbat Damun

Khirbat al-Damun / Elle Flanders & Tamira Sawatzky

חלדה / Khulda

מג'דל יאבא / Majdal Yaba

קולה / Qula

קולה / Qula

ספסאף / Safsaf

סעסע / Sa'sa

סטאף / Sataf

טיטבא / Taytaba

אם זינאת / Umm Zinat

מה שאיננו / What isn't there

לאנדרו קורא / Leandro is reading

מבקרים בתערוכה "מה שאיננו" / Visitors at the exhibition "What isn't there"

חלל התערוכה / The exhibition space