“…How I awakened one solitary night to hear an unfamiliar voice, turned in its direction and saw my elderly, blind father holding a lemon in his hands, bringing it near his lips and kissing it again and again, cut off from the world, completely alone, he and the lemon. Tears streaming from his extinguished eyes wash over the lemon as he embraces it with devotion.”

Bashir alHayyari, Letters to a Lemon Tree, AIC

1. Material culture as text

We can learn about different cultures and different periods from materials and from objects. Objects and raw materials serve as texts that contribute to the knowledge assembled in fields such as archeology, anthropology and cultural studies, and help tell the story of social phenomena over time.

The practice of collecting objects, categorizing them, preserving and displaying them in different ways in the past and in the present, is itself an interesting setting for examining cultural issues and understanding systems of social power involving questions of centrality vs. marginality, high vs. low, spiritual vs. material, etc. A storeroom, living room, courtyard, collection, drawer, junkyard, marketplace, museum, fair – all are spaces in which objects are collected for various reasons that reflect our attitudes toward them, and the discussion we wish to conduct with and through them.

The starting point of “Amnesia” is the examination of how objects are designed and constructed in the context of social and political relations in general, and the Nakba in particular. What characterizes the objects that were part of the daily life of Palestinians at that time, and how do they reflect the way of life of a society in transition from agriculture to urbanism, how the texture of this life was destroyed and how it was transformed in the wake of the trauma experienced by Palestinian society during those years? An additional perspective is that of the dispossessed Palestinian refugees themselves, who often had to react with little or no warning and decide what to take with them and what to leave behind. Which objects and life-sustaining materials are important for physical and psychological survival, and which can be abandoned. These considerations, against the backdrop of our knowledge about the difficult conditions created by the Nakba, make us think about those things for which the refugees yearned so strongly because they had been forgotten at that fateful moment, or arbitrarily left behind. Many Palestinian refugees preserve objects from their villages and towns as prized possessions, which they hold onto as representations of a reality which once existed and is no more.

Objects from that period can also be looked at from a material-technical point of view. It is interesting in this connection that the period is one in which objects made by hand by the local population co-exist with those that are mass-produced by industrial processes: a sewing machine made by “Brother” next to a charred, blackened hand-carved ladder made of branches gathered locally. Objects from this period have a strong local feeling, of local materials, traditional, rooted ways of life, similar to the ways of life that the Zionist immigrants tried to acquire as they adapted to the area.

Reading the objects that have been preserved from the period preceding and following the Nakba, studying them, will teach us a great deal about Palestinian culture, and looking at them will allow us to have a deeper discussion of relations between the conqueror and the conquered, the attempt by the former to sever the connection between Palestinian society and its material resources, on the one hand, and of the latter to preserve its identity and memory by means of these objects.

2. Objects and consciousness: A visit to the collection of the Committee of the Uprooted in Nazareth

In preparation for the exhibit we went to see the collection of objects belonging to Palestinian refugees in the Nazareth offices of the Committee of the Uprooted. Objects that had been left behind by refugees and those who were uprooted from their localities were collected by Amin Muhammad Ali. The collection is displayed during various events sponsored by the Committee. It consists of a different kinds of objects: copper pots and utensils, agricultural equipment, clothing, tools, cooking equipment, storage containers, etc. The personal aspect we sought could be found in a number of objects, such as a basalt stone that had been worn by being used to sharpen knives, an elongated fired-clay container that had served as a beehive, a few letters, a blanket filled with hair sticking out of tears in the fabric, etc. The objects tell their stories silently, and attest mainly to the absence of their owners. It’s easy to weave from them the daily routine, along with the chilling feeling of the routine that was disrupted. Viewing the collection made us focus on the question of how it is possible to create objects that defy the absence of the individual and the group. How can we rethink the connection to the Palestinian refugees and respond to their absence? Can memory be reconstructed materially, in a language of objects?

3. From idea to object – reflections on amnesia

“Amnesia” asks whether objects are capable of arousing the memory of the Nakba, given the amnesia that characterizes Israeli society: A group of artists investigates whether material culture can be used to create a dialogue with Palestinian refugees.

Ido Bruno’s work, “Holes in the memory,” consists of a piece of basalt placed on a cedar plank next to a mass of roasted wheat grains and sesame seeds held together by epoxy that resembles the sap of the almond tree. Viewers are asked to rub the basalt against the mass of wheat and sesame and smell its fragrance, in a fruitless attempt to recapture the odor of an unknown entity, of a refugee, a personal space from the past. Bruno uses odor, the most personal of senses, to symbolize the yearning for what is missing, and at the same time indicates how elusive it is and how hard to recall.

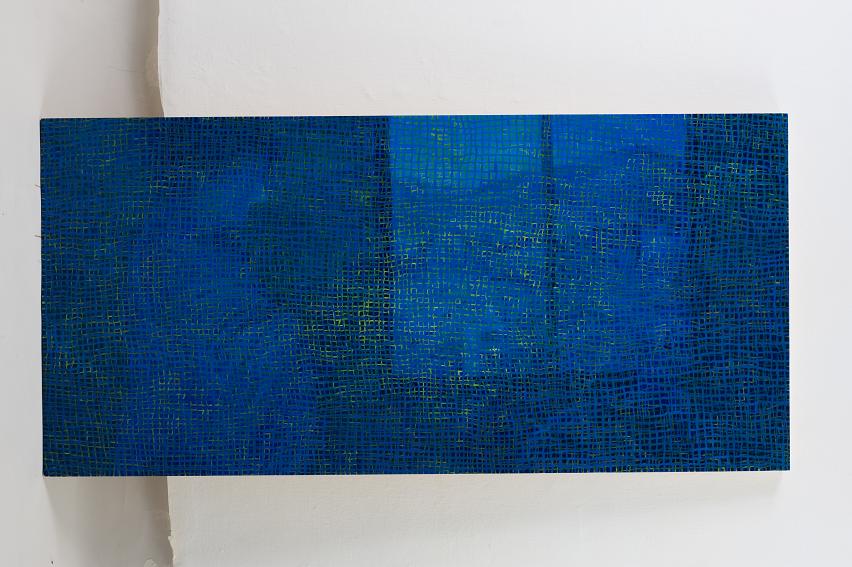

David Goss portrays an imaginary scene from the visit to the collection of the Committee of the Uprooted. The picture, “Yasmin, Committee of the Uprooted: Nazareth,” is painted over one of Goss’s previous works. It shows Yasmin Dahr in the space where the collection is exhibited. Yasmin is seen through the window of the darkened room, looking outside, as if she wanted to get out, trapped in a web of nets that push and cram her in. Her view of the sunlit hills of Upper Nazareth distances herself, on the one hand, from her surroundings, and traps her, on the other, in the exhibition space. The colorful atmosphere of the painting, and its dull aspect, give it a bleak feeling even though the visit occurred in the middle of the day.

Zivia’s piece is called “Take Away,” a basket-shaped object made of cypress cones and strips of checked fabric torn from work clothes. Sterile cypress trees whose fruits are also barren were planted by Jewish settlers in place of fruitful olive trees, with the encouragement of the JNF. The cones are woven together with the clothes of the Jewish settlers, thereby signifying their presence. zivia recalls that, when she was a child, Palestinian women came with their baskets to the place she lived, collecting wild plants whose value was known only to them. “Take Away” is a piece constructed like a disintegrating basket, full of holes, likw one that may have been taken to the market, or perhaps used to carry sand at a construction site. The basket is a gesture to the women who were removed from the places where they belonged, and who return carrying baskets to collect the produce from their lands.

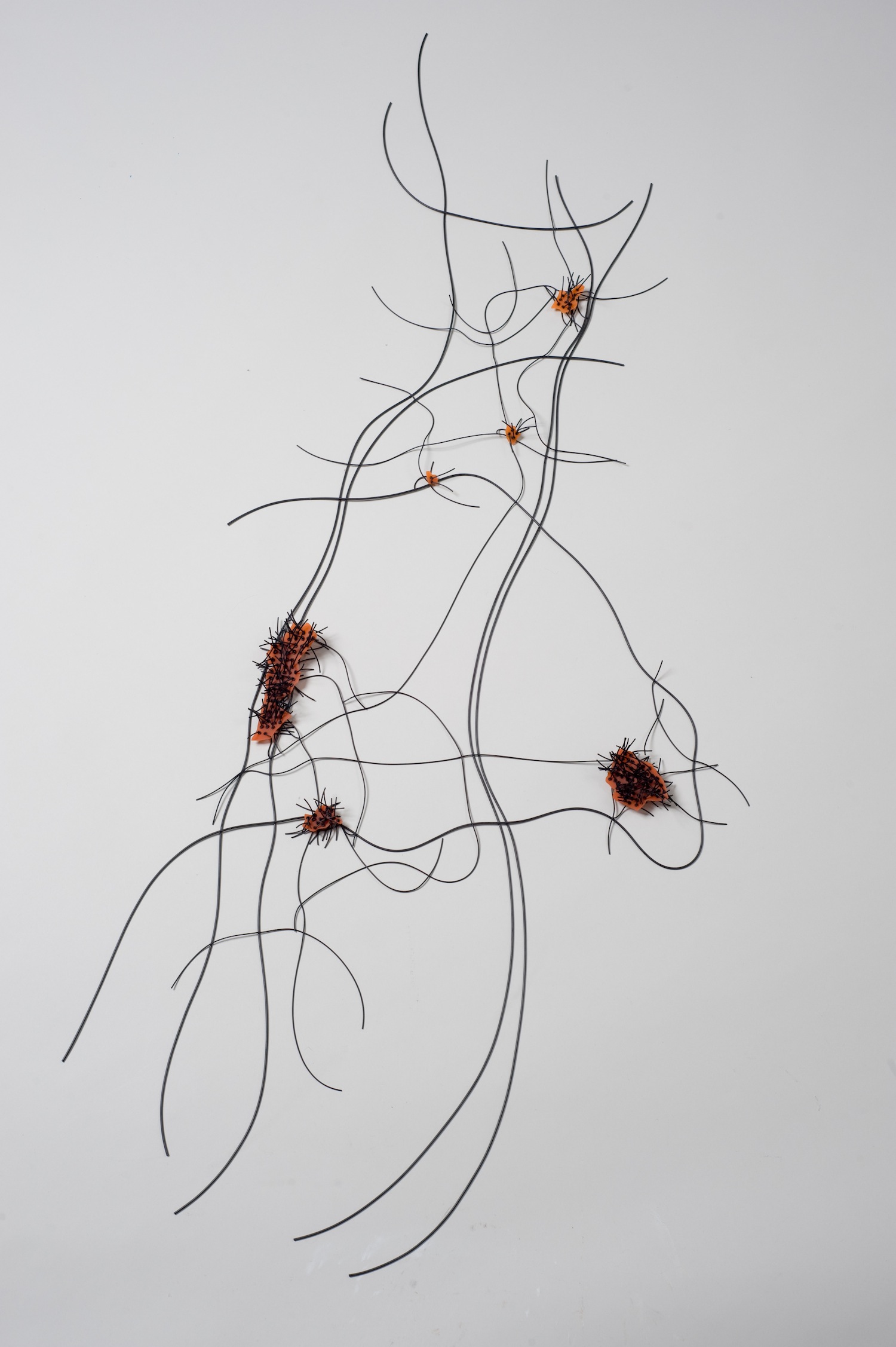

The transparent Tel Aviv map on Einat Leader’s “Orientation Jewellery” exposes the elusive nature of representation. The nature of a map is to represent a physical reality in a manner that allows users to orient themselves in space. Leader’s “Orientation Jewellery” undermines the feeling that we know where we are and points to an additional cognitive space, one revealing the practice of concealment that is achieved by constructing an alternative body of knowledge in place of the original one: a city map that enables us to know that we are somewhere else. Leader transforms the map of Tel Aviv that we are familiar with into an ethereal array of spaces in a network of black rubber strands representing its streets, similar to the schematic portrayal often found on the margins of maps, on a pale background and with little detail. The destroyed Palestinian villages that were once located within today’s Tel Aviv municipal boundaries, which are so transparent to Israeli consciousness as to be invisible, burst out of the map. The web of rubber strands allows it to be worn, and turns it into an interpretive key to both the personal and the public space.

Ravit Latzer’s installation, “443: Human Remains,” displays rough ceramic peels (both fired and unfired) on which she has drawn the signs of the Israeli regime as they appear along Route 443 (the “Modi’in bypass” road from the center of the country to Jerusalem). Latzer also uses cotton kerchiefs of the kind employed by Moslem women to gather their hair beneath their headscarves (in Arabic: “kamta”). She unravels them and also wraps them around the ceramic pieces. They move among three dimensions: head coverings, white flags of surrender and wide bandages. The installation embodies the tremendous pain stemming from the encounter of power and its representation with the objects on which it operates: physical, sexual and national.

Gad Charney’s “Ghost” reconstructs and recycles the image of the finjan, the traditional Arab coffee pot, defying the standard formats used to represent Palestinian culture: humus, falafel, Turkish coffee, darbuka (a small drum, open at one end, held between the knees and played by hand), kafiyya, and the like. Charney shows us this format, creating it from recycled plastic as if it were a restless ghost. The coffeepot, which incorporates a rich and glorious culture, becomes transformed by the clichés of Israeli orientalism into a mere three-dimensional object lacking any true meaning, one that disintegrates and is recreated. Charney translates this conception into a patchwork, a useless and colorless mirage constructed out of a world of cheap plastic, on the verge of disintegration, emptied of its rich, lush, fragrant associations.

“Two Pieces of Information” are two filmed stories created by Ami Steinitz. The pieces of information are two objects whose stories embody the Palestinian way of life before the Nakba. One is a hive used to make honey. Daud Badr’s mother used some of the honey at home, and sold some to neighbors. Lutfiyya Sam’an uses a headscarf and beadwork embroidery to describe a rich tradition. Steinitz extracts from the stories of these objects the cultural strata they signify, including their social, economic and artistic aspects. At the same time, using these objects, Daud Badr, originally from al Abasiyya, and Lutfiyya Sam’an, originally from Suhmata, recount how they were uprooted from their lands.

Yasmin Daher, a young Palestinian poet, responds in her poems to the works in the show. Her writing lets her create a circular, reflexive movement having multiple layers of personal reaction, knowledge and interpretation in which all the artists, as well as their works, simultaneously serve as both subjects and objects. Daher’s poems allow us to look directly - personally - at the works in the exhibit. The connection between the artworks and the written word adds new layers of meaning to the exhibit and makes the objects shown possess a dynamic rather than a static character. Daher, as a Palestinian woman confronting the reality of Israel, moves in her poetry between a private biographical world and one that is self-conscious and definite.

אמנזיה - עבודה Zיויה / Amnezia - Work of Zivia

אמנזיה - עבודה עינת לידר / Amnezia - Work of Einat Leader

אמנזיה - עבודה רוית לצר / Amnezia - Work of Ravit Latzer

אמנזיה - עבודה דיויד גוס / Amnezia - Work of David Goss