"I put a picture up on a wall. Then I forget there is a wall. I no longer know what there is behind this wall, I no longer know there is a wall, I no longer know this wall is a wall, I no longer know what a wall is. "

Georges Perec (1974) Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, 2008

***

Norma: How did you begin these works?

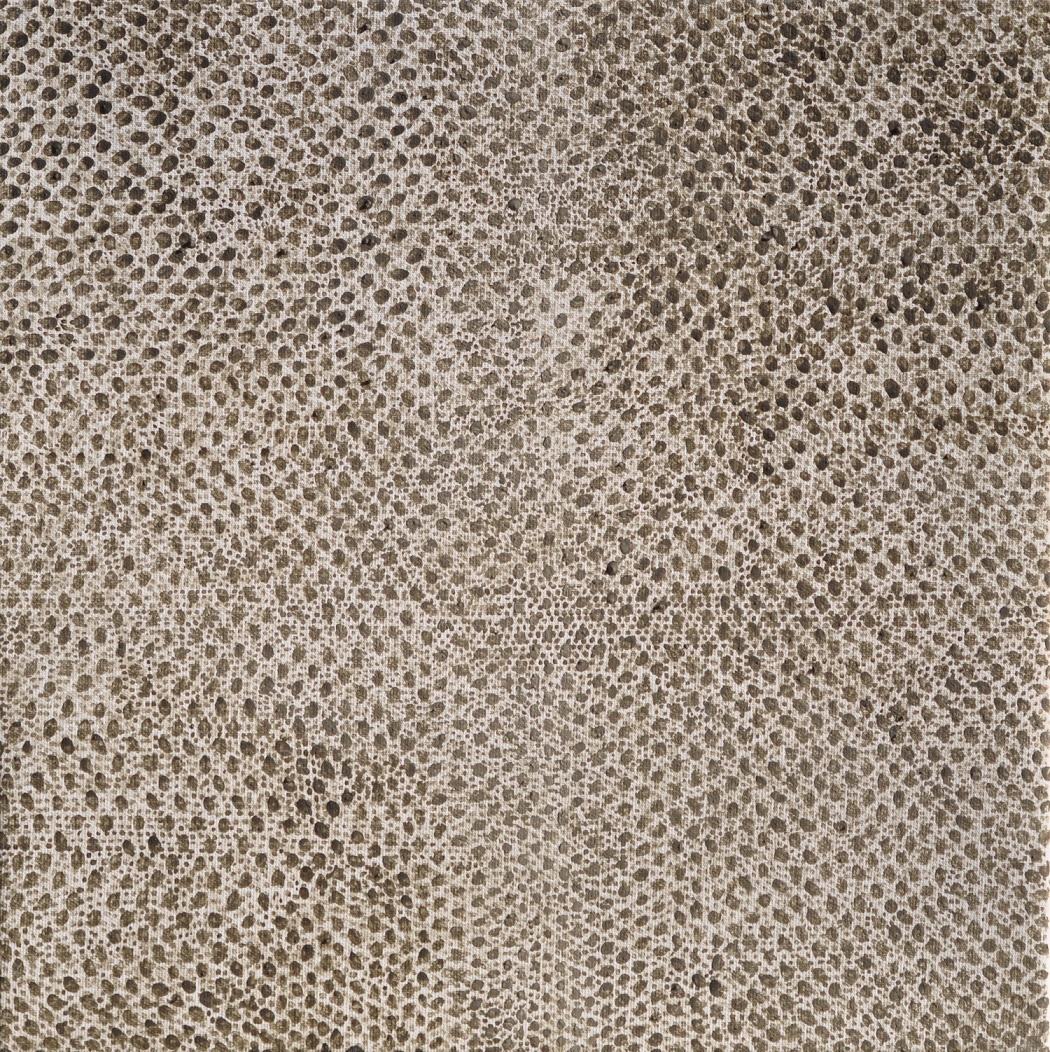

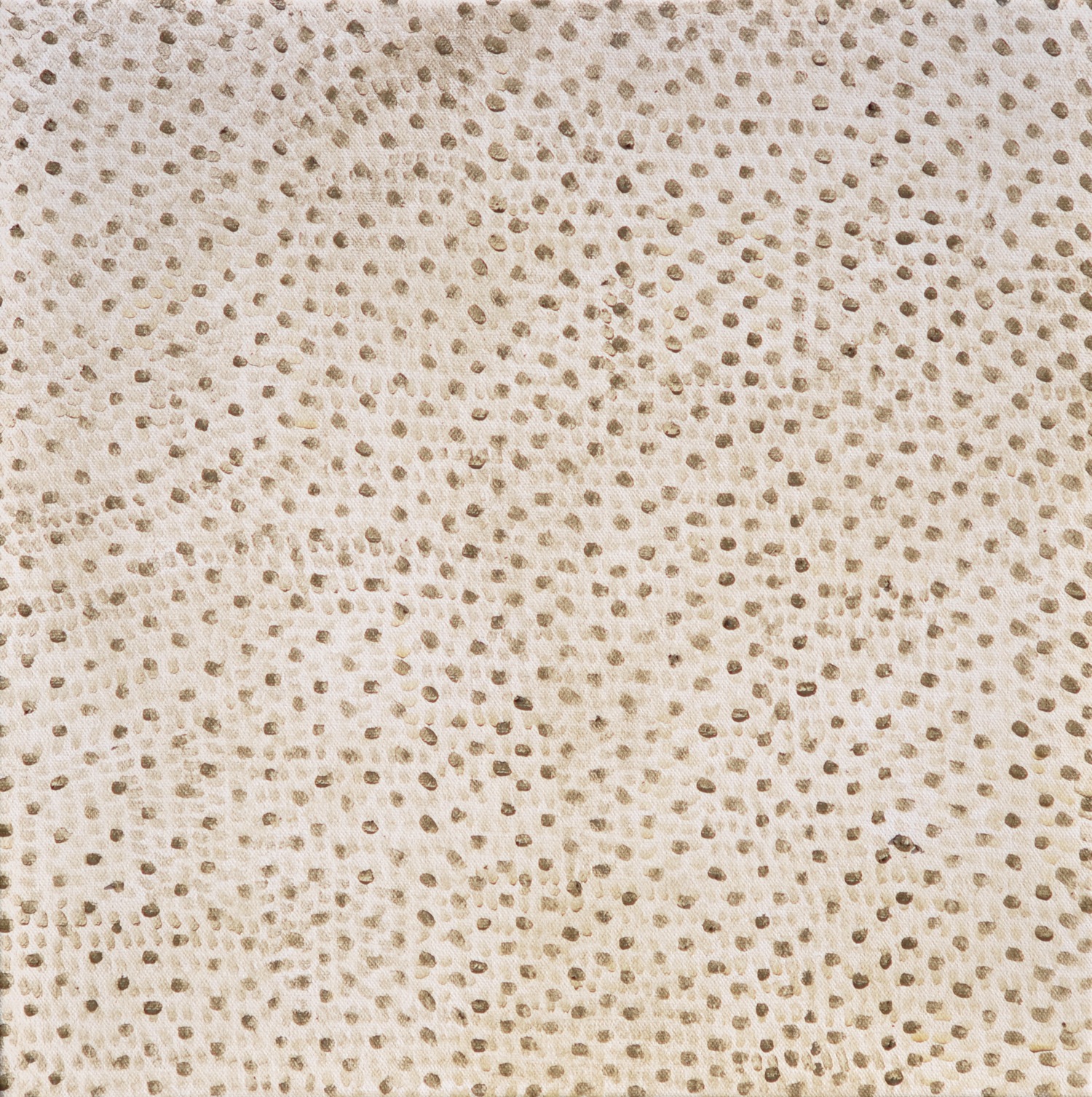

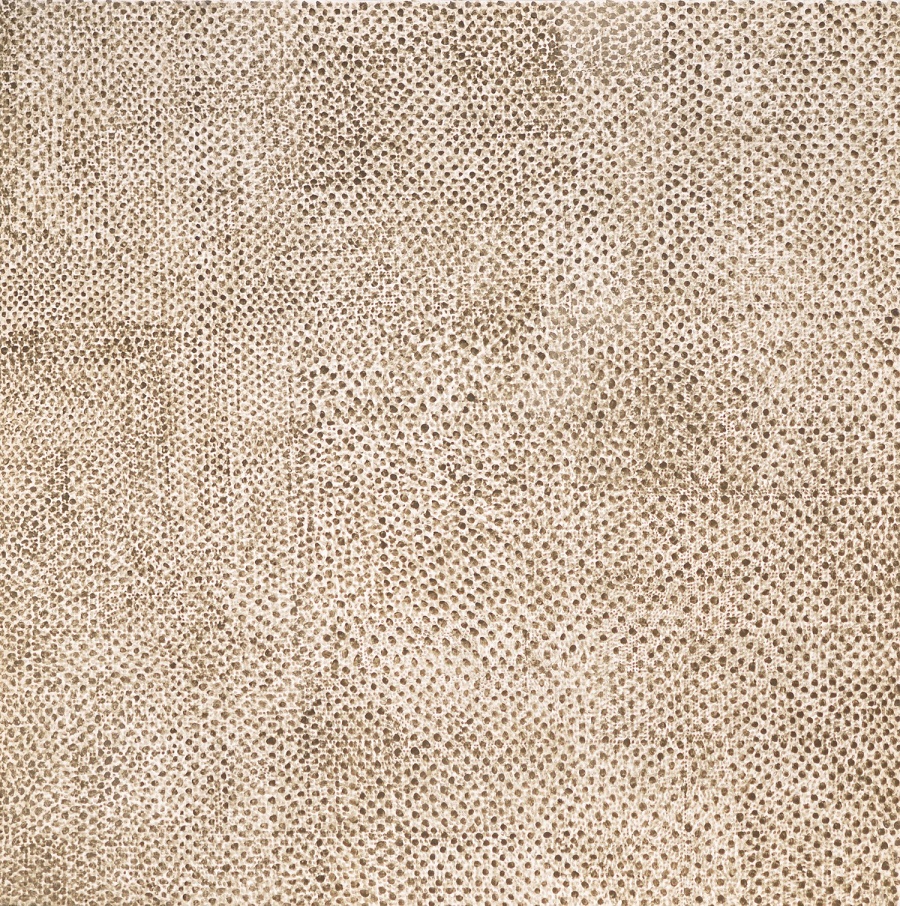

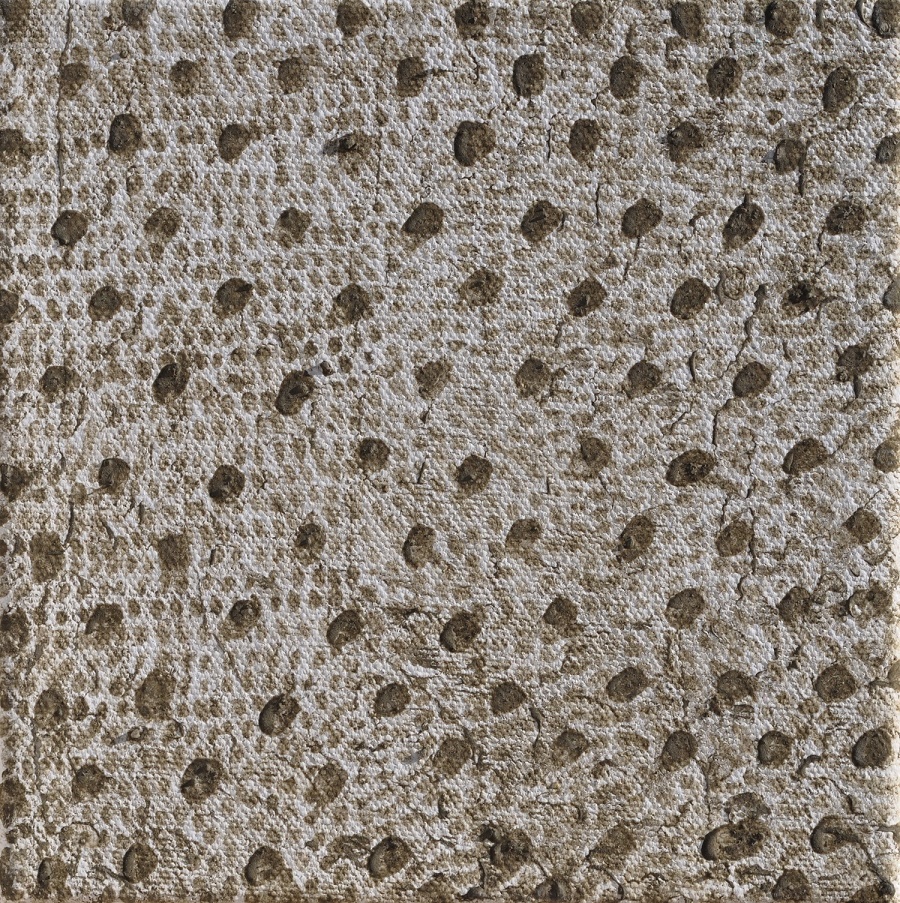

David: These paintings origin was in the material, a combination of the paint medium and the subject. The two developed simultaneously. The paintings are done in tempera mixed with cement: a kind of concrete compound I prepare and place on the canvas. The paintings hung on the wall, create the impression of a wall, or actually are the material of a wall.

Norma: They also construct a wall.

David: They make a visual wall. The painting is based on the viewer’s ability to see the canvas more or less clearly. A kind of reticulation, that blocks or seals the brightly illuminated white canvas. Creating the painting involves, essentially, constructing a visual wall.

Norma: Constructing a wall in each painting separately and by all of them together?

David: Right, each painting on its own is a kind of wall, or a grid that blocks one’s vision. The paintings block one’s sight, and at the same time comprise a tonal network, shades of gray – a grayscale – ranging from bright white to the very dark gray of the cement, which is completely opaque.

Norma: Your palette is very limited.

David: Yes; since I’m only using the tempera medium, and cement as a pigment, the tonal range is minute. It’s minimal. But there’s still variability. In fact, these small nuances become very significant. When you mix the colors, the relative proportions of water and egg greatly affect the cements' saturation. The density of the dots, the pixels, affects the eye reception of each painting. Also the way the paint is applied, how quickly, in which direction, also creates variety.

***

Norma: It’s very hard to focus on the paintings.

David: Yes, the paintings are very dynamic. The main cause of the dynamism is that I wasn’t very precise, because if I’d worked precisely they would have been less dynamic. Even though painted dots naturally vibrate when viewed, the non-uniformity, the distances between them create an illusion of waves. Thus, the dynamism results from touch, from the hand, the painterly act.

Norma: You could almost fall in love with this material, in the sense that you wouldn’t even want to see through it, to see what’s on the other side.

David: In a sense, the builder of the wall, loves it. Neither the viewer or the creator are the center; the wall/painting is what’s important. It provides the principal material evidence of itself, no one cares what’s on the other side, it – the wall – becomes the be-all and the end-all.

***

Norma: Can you tell us something about the painting’s layers during your work process ?

David: Each painting has a number of painted layers, with a different rhythm and scatter of dots – short brush strokes, which create the strata and the rhythm of the works. Every detail is important. Every dot is important. The whole is constructed from its details; the dot is the smallest syntactical element, the digital pixel. That’s how the syntax of the works is created.

Norma: I’m interested in the choice you made: to build a wall out of little dots.

David: My choice stems from my interest in the political, the meeting of impossible extremes, the desire to address through painting Israel’s largest and ugliest cultural construction. If Israel will be remembered in world culture it will be as the state that built a concrete wall some 760 kilometers long that only caused economic and emotional damage, injustice. A monster is being created here that is becoming Israel’s cultural heritage. The wall is visible or reflected in the painting through a kind of x-ray. The paintings are a kind of incursion into the wall itself – into the metaphorical space between the molecules of concrete. A painting is something hung on the wall, but is also a kind of wall. The painting needs the wall, it conceals and covers it. There’s a moment when we no longer see the paintings, just as we no longer see the walls.

Norma: Even in your painting, no matter how much we try, we can’t see anything. I get lost in it. I look, try focus on some portion, and for a moment I think I see something. But it’s only for a second, because the image disappears immediately.

David: You’re right. Sometimes I also think I see something, or perhaps I’m only hoping to see something. Although I know I did not paint anything.

***

Norma: The painting of the wall also needs the other paintings alongside it.

David: Yes, they need the context. The multiplicity and the expanding space – they’re constructed from them. Just as the dot needs the other dots nearby, the individual painting, and thus all the paintings, are parts of a greater whole. Despite the whole, there’s something about this work that strips walls bare, exposes what’s behind it.

Norma: How does it expose what’s behind?

David: In the tradition of the Italian Renaissance, the painting becomes a window onto an ideal reality. In the Dutch tradition, the painting mirrors reality. Here the painting emphasizes and reflects what’s behind it. What it conceals. To deal with walls, fences and paintings is to deal with vision. The wall physically blocks the view; painting is intended to open it up again.

Norma: The wall built by the Israeli government, supposedly to separate Israelis from Palestinians, in fact closes us in. Cages us, and purposely blocks us from seeing.

David: Right, we’re also in a ghetto.

Norma: The wall leaves us no choice other than to see ourselves, and only ourselves.

David: Yes, that’s the paradox of the fortress, which is also a prison, or a ghetto. You build fortresses that are supposed to protect you or seal you off, but what happens is that they also restrict your world and your field of vision.

Norma: Also in a political sense.

David: Of course.

Norma: You construct the wall in the studio; you construct it in the gallery and close yourself in with your own hands.

David: Yes, the act of painting becomes a form of self-incarceration. Painting, which should usually open up the world, limits the field of view. Although the paintings are abstract, there’s something very tangible about them. They represent a powerful material reality. In fact, they’re made of concrete. That’s a very real material, actual – “concrete.” My fantasy is that the viewer can penetrate these paintings, use them to pass through a wall. The paintings transform the concrete into something more ethereal. I don’t want to say “lyrical,” but certainly transparent to some degree.

Norma: Perhaps the transparency lies in the place of the wall in our lives as Israelis. For us it’s transparent.

David: Right – we see the wall as natural. We pass the wall but we don’t see it.

Norma: It becomes part of our landscape.

David: Yes - only someone living outside the ghetto and looking in can understand how abnormal this situation is. We can’t see beyond our narrow conception of reality, a reality constructed out of a partial view of the world that is therefore, at best, inexact. Everyone’s conception of reality here has been built over years in a false and mistaken manner. Although the wall is very real, it’s also a metaphor for Israeli societies' ability to see.

Norma: In fact, every Israeli locality is surrounded by a wall. Kibbutzim, moshavim, even the university. Palestinian localities have no walls or guards.

David: It’s the “tower and stockade” mentality. A siege mentality.

Norma: It’s terrible to live walled-in all the time. Think of the effect on our relationship to places and to people, to those on the other side of the wall, and to ourselves.

David: Everyone here surrounds themselves with walls. Neighborhoods close themselves off with private security guards. We’re continually drawing boundaries and seizing territory.

***

Norma: Must you sense a wall, understand it, in order to create one?

David: What do you mean, “understand a wall”? Were I to bring cement blocks into the gallery, and build a wall, would that convey the feeling more successfully? Or if my painting were more figurative, would that have conveyed a stronger sense of a wall? I chose an option that gives the viewer a central role in the experience. His vision constructs what he sees. The viewer plays an active role in constructing the wall. It’s a phenomenological experience. Other forms of representation provide viewers with conclusions, and actually distance them.

Norma: What relationships do you want to develop between the work and its spectators?

David: The work will be exhibited in Zochrot’s gallery, a location whose political context is clear. I’m skeptical as to whether the paintings can really have any effect, and I’m pessimistic about any future relationship with the spectator. On the other hand, and now I’m contradicting myself, I think that cultural activity in Israel must address these issues. Regardless of their immediate practical effects, moral positions are significant in the long run. Finally, this is how I, personally, deal with the situation. I create, but I also observe – I’m very emotionally involved. It’s a kind of “therapy.” It’s like a mantra – I’m dealing with the issue with each dot I place on the canvas – I’m both building the walls and, at the same time, struggling against them.

***

David: There are also people on the political right who oppose the wall. It interferes and obstructs their political fantasy. It’s one of the worst options. It’s also terribly ugly in an aesthetic sense. So long as there’s no wall, everyone can dream. The Palestinians can imagine and so can we. The wall undermines such dreams, destroys everyone’s fantasies. Those who built the wall didn’t consider how they themselves would be affected by it. My paintings are one aspect, one part of the reality. And also a search for fantasy in a reality made of walls. An attempt to create a little more space.

***

David: Our view, our ability to see things, is socially constructed. As is our unwillingness or inability to see things. This social construction is fundamental. I think that art in general, and painting in particular, must deal with these cultural constructions.

***

David: That’s one of the problems I have with photography. Even increased exposure to photographic documentation fails to deal with those cultural constructions. It’s partly a result of our own physiology, our stimulus threshold.

Norma: I don’t agree with you. I think that if we learn how to look, we’ll be able to see what’s in even the millionth photograph, to ask what’s missing and to create a connection between us and those we see in the photo.

David: That’s a very optimistic statement, as if some image could appear that could make a difference.

Norma: No, I think it could happen with many images – even with any image. We don’t have to wait for the image that will make it happen. It’s the result of the choices we make, how we see, and comes with practice.

David: I think you’re wrong: regardless of how much knowledge a person has of art, or how well they understand the media, people are very skeptical about photographic images because they’re viewed as tainted, biased – they’re not innocent. The image threatens their worldview. And people don’t want images to alter their worldview.

Norma: It’s not the image that brings about the change, but how the image is viewed.

David: So the image won’t change that person’s worldview. Even if you show someone thousands of images proving their beliefs are wrong, they probably won’t change what they think.

Norma: But that’s exactly what we’re doing, as people dealing in images – attempting to create conditions in which images can be viewed. We have to obtain additional images, write about them, talk about them. No image – any image, either a photograph or a painting – stands alone.

David: Right, we have to deal with how our view is constructed. I think that painting, because the mediums' manipulations are visible, is the most appropriate means to approach these constructions. The photograph creates a mechanism which 'locks in' to the observer’s personal credo.

Norma: I think that depends on what’s done with the images.

David: Paradoxically – speaking as one who believes in a “dead” medium – painting not on a wide scale, creates the opportunity to penetrate these constructions.

Norma: Painting, but also photography.

Myopia / Painting b

Myopia / Painting c

Myopia / Painting d

Myopia / Painting i

Myopia / Painting e

Myopia / Painting f

Myopia / Painting g

Myopia / Painting h